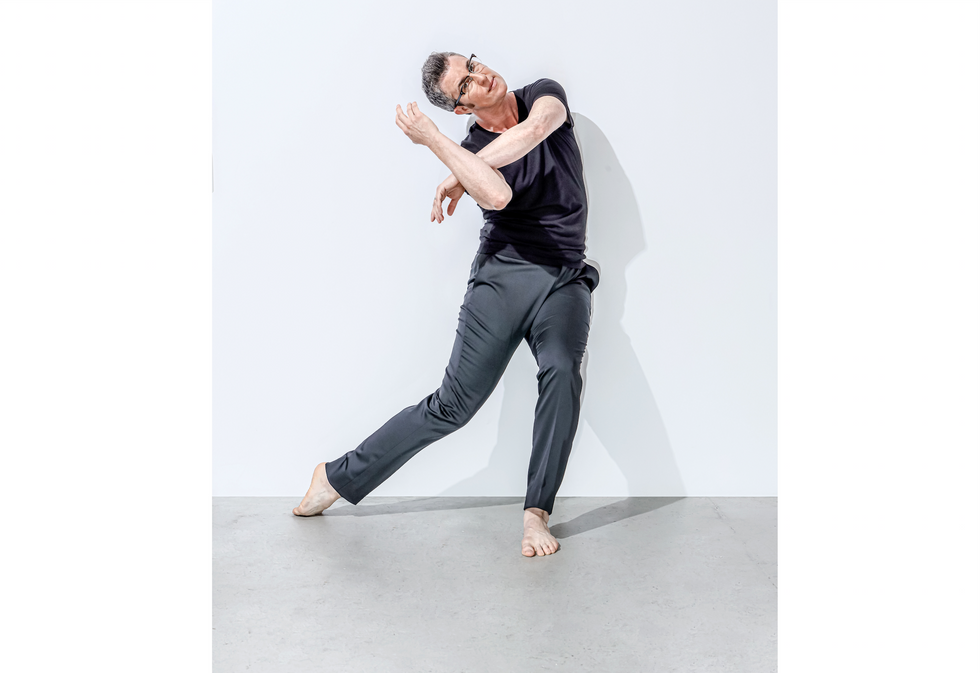

Pioneering Trans Artist Sean Dorsey Is on a Mission to Reshape the Dance Field

Sean Dorsey was always going to be an activist. Growing up in a politically engaged, progressive family in Vancouver, British Columbia, “it was my heart’s desire to create change in the world,” he says. Far less certain was his future as a dancer.

Like many dancers, Dorsey fell in love with movement as a toddler. However, he didn’t identify strongly with any particular gender growing up. Dorsey, who now identifies as trans, says, “I didn’t see a single person like me anywhere in the modern dance world.” The lack of trans role models and teachers, let alone all-gender studio facilities where he could feel safe and welcome, “meant that even in my wildest dreams, there was no room for that possibility.”

But even impossible dreams can come true. Now in its 15th season, Dorsey’s award-winning San Francisco company, Sean Dorsey Dance, is heralded for intersectional dance-theater works that celebrate trans, gender-nonconforming and queer identities. Along the way, Dorsey, 47, has become the first trans choreographer to receive funding from the National Endowment for the Arts (seven grants to date, totaling $115,000), and the first U.S. trans artist presented by the American Dance Festival and New York City’s Joyce Theater.

Today, he’s the role model he always wished he had.

Lydia Daniller, Courtesy Dorsey

As a high-school theater geek, and even while taking community dance classes and double-majoring in political science and women’s studies at the University of British Columbia, Dorsey had no inkling of his potential in dance. He spent his time joining any social justice clubs he could find, and introduced the first recycling program at his high school.

Then, during his first year in Simon Fraser University’s graduate program in community economic development, he started taking ballet in the evening. “My teacher said, ‘Have you ever thought about being a professional dancer? I think you have what it takes.’ My world just exploded.”

Already in his mid-20s, he put his education on hold to enter a two-year modern dance program at a Vancouver dance school. His first piece of choreography, a five-minute queer-themed duet, got an enthusiastic response.

“The next day, the studio director sits me down and says, ‘Your piece last night made people feel very uncomfortable,’ which I knew wasn’t true. In that moment, all the years of not seeing anyone like me, all the gendered stuff like costuming and bathrooms and changing rooms, came flooding in, and this light bulb went off. I just found my calling.”

Dorsey realized that his art could advocate for—even demand—equity for trans and queer people. “Although I never imagined that dance would be the vessel for my social justice work, it does make perfect sense,” he says. “Dance is this visceral form of communication, and it can connect you deeply with an audience and lead to identification, empathy and compassion.”

He headed to San Francisco, where he performed with Lizz Roman and Dancers for six years while choreographing and performing his own work as an openly trans dance artist. But like any pioneer, he had to break down barriers. “There were so many folks who would never pick up the phone to talk to me,” he says. “As a trans artist, the assumption was that the craft would be poor, and there might be no audience or context. They were like, ‘Oh, you mean drag.’ ”

With almost no one willing to produce his or other trans artists’ work, he decided to do it himself. He launched the annual Fresh Meat Festival of trans and queer performance in 2002, and SDD two years later.

Melding abstract movement and theatrical dialogue, endearing humor and deeply personal storytelling, Dorsey’s choreography offers an array of access points into challenging material. His first evening-length work was 2009’s Uncovered: The Diary Project, based on the personal archives of trans pioneer Lou Sullivan. The Secret History of Love, about LGBTQ relationships in the years before gay rights, followed in 2012; then the AIDS-themed The Missing Generation in 2015 and Boys in Trouble, which unpacked toxic masculinity and white supremacy, in 2018.

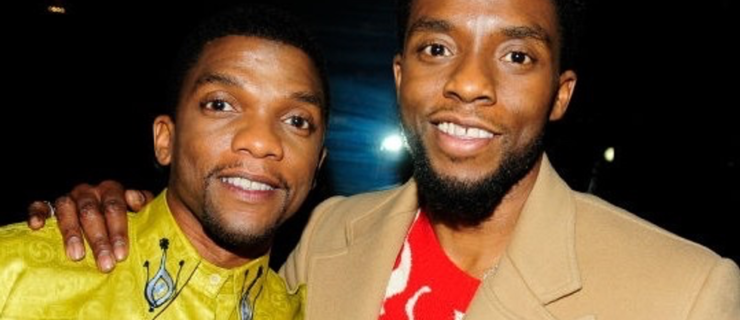

Sean Dorsey Dance in

Boys in Trouble. Dancers, left to right: Will Woodward, Sean Dorsey, ArVejon Jones, Nol Simonse (top of head), Brian Fisher. Kegan Marling, Courtesy SDD

In performance, in conversation or in his equity work, Dorsey directly calls out racism, gender bias and privilege. “I’m so impressed that as powerful and staunch an advocate as Sean is, he always leads with warmth and love,” says Christopher K. Morgan, executive artistic director of Dance Place in Washington, DC, which has co-commissioned three SDD works. “It’s such an incredible way to effect change.”

Those flawless people skills—along with serious grit and strategic community engagement—have been one of Dorsey’s most powerful tools.

“I work for months in advance with theater partners,” he explains. “With The Missing Generation, I would help identify a local AIDS organization, an LGBTQ seniors organization and a trans-youth nonprofit. They get free tickets, you build relationships and that theater is getting a new audience, new volunteers, new donors. It all goes back to my background as an activist—I’m thinking about that full arc.”

On SDD’s nationwide tours, Dorsey also leads dance workshops that support all genders, all abilities and sizes, and all races. “Almost everyone is there as their first dance class,” Dorsey says. “They’ve never felt safe or supported enough to go into any kind of a dance-learning environment.” After introductory meditation and body-positive affirmations, Dorsey teaches beginner-friendly movement and adapts it in supportive ways.

“They didn’t let me sit on the sidelines,” says Oliver Nepper, 28, who identifies as trans-nonbinary and uses a wheelchair. In Dorsey’s workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, “they were like, ‘You can do this turn a little bit faster, or do it on this beat instead of that so you can get to the next step.’ I gained a big confidence boost because of Sean’s positivity and encouragement.”

“Everyone feels a community bond instead of feeling othered,” says Nicky Martinez, 25, who identifies as gender-fluid and Latine, and has taken two workshops in San Francisco. “As a person who is plus-sized, I always felt uncomfortable as a mover. Being seen and visible in that setting is really special.”

Leading the workshops helps refuel Dorsey for the rest of his work. “It’s this amazing space where being trans or gender-nonconforming is something to be honored,” he says. “It’s one of my absolute favorite things to do.”

Dorsey teaching a workshop in Boston

Courtesy SDD

Even SDD’s tech rider serves as an element of activism: It requires theaters to make their facilities all-gender during the company’s run. As a result, many theaters have made their lobby restrooms and backstage facilities permanently all-gender.

At The Joyce, emcees now greet audiences with “Welcome, everyone” instead of “Welcome, ladies and gentlemen.” “Every time I hear somebody say, ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen’ now, I want to cringe,” says Linda Shelton, The Joyce’s executive director.

Not all tour stops are as welcoming. In North Carolina in 2017, local “bathroom bills” and anti-trans activism meant Dorsey was often unable to use a restroom that was legally or physically safe for him. In one case, SDD member ArVejon Jones recalls, “I stood outside for him at an airport to make sure he was okay.”

These days, presenters not only pick up the phone when Dorsey calls, they invest in his work: His next evening-length production, The Lost Art of Dreaming, is co-commissioned by ADF, Dance Place, 7 Stages in Atlanta, Velocity Dance Center in Seattle and San Francisco’s Queer Cultural Center.

“It explores expansive futures for trans, queer and gender-nonconforming people,” explains Dorsey, who will do movement research in DREAM LABS held during SDD touring residencies. “DREAM LABS are spaces where I ask local folks to creatively express what they most wildly want and dream of,” he says.

Dorsey’s vision for the future includes more professional-quality training for trans and gender-nonconforming dancers, inclusive dance curricula and trans teachers, and trans leadership in art institutions. He also wants to commission trans, gender-nonconforming and queer artists of color through his program Fresh Works.

And he’d eventually like to take a vacation with his partner of 18 years, the trans singer-songwriter Shawna Virago. “This is my heart’s passion, but it’s also super-exhausting,” Dorsey admits.

Despite the challenges, he remains hopeful. “The wonderful part about the ‘trans moment’ is that it has afforded more trans literacy to presenters, programmers and funders,” he says. “I know that the future is going to be better, because young trans people are able to see themselves reflected in arts and culture. They can finally imagine there’s a place for them in that world.”