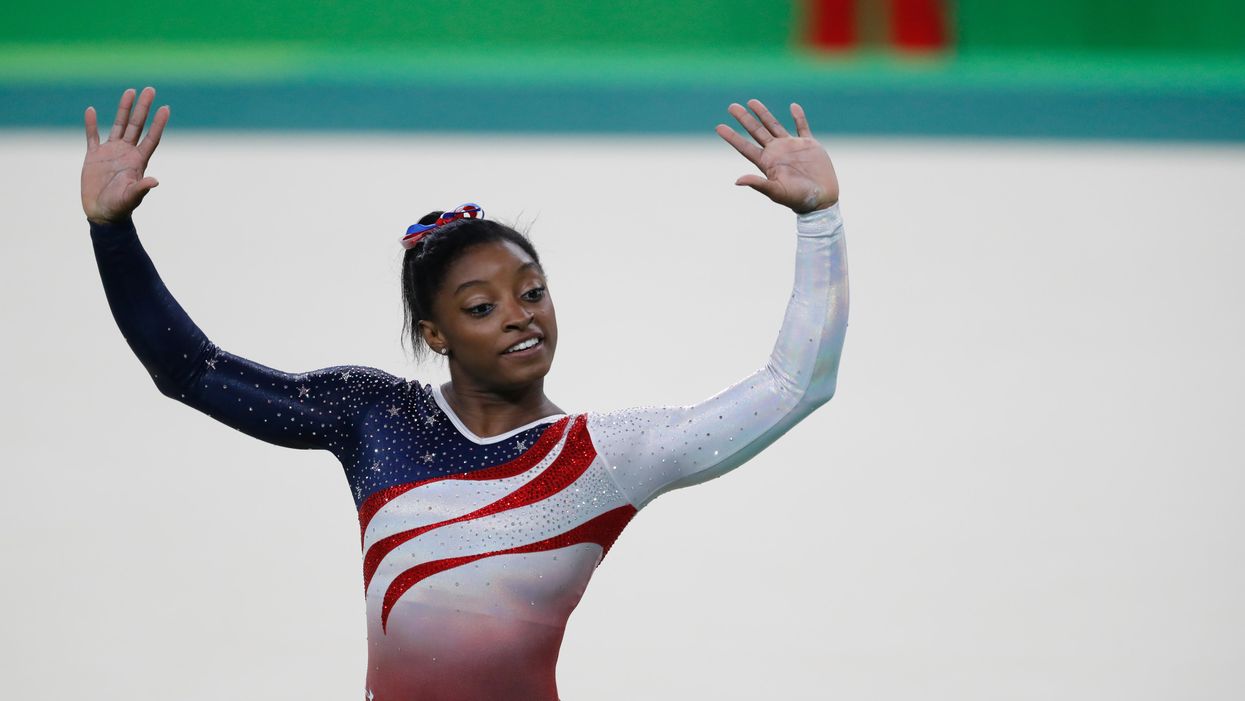

What the Dance World Can Learn From Simone Biles and Team USA

In the heat of the women’s team gymnastics final, a shaken Simone Biles withdrew from the Olympic event last week to protect herself and her teammates. Her courageous decision to prioritize her health was met with overwhelming support, including from former U.S. Olympic gymnast Kerri Strug, who competed through extreme injury at the 1996 Olympic games and subsequently retired at 18 years old.

And yet, praise for Russian gymnast Artur Dalaloyan’s performance in the men’s team event highlighted his Achilles surgery in April and questions over whether he was healthy enough to compete.

I love that, although most of us dancers are not Olympic athletes, we treat every performance like the Olympics. But, like the Olympics, the dance world is plagued by the contradictory values of self-care and “team effort” heroism.

As dancers, we are strong-armed by the fleeting nature of a performance career. Before we’re even out the door, the “team” for which we injured ourselves—our twisted badges of honor—has often already replaced us. We attempt to resist this expendability by pushing through pain and injury to nobody’s detriment but our own (and, sometimes, our unfortunate dance partners). Ultimately, what we only thought was inevitable becomes inevitable by our own doing. We retire earlier than we should, and with broken bodies and spirits.

Even when verbally encouraged to take care of ourselves, our current dance culture expects us to perform at all costs. Sometimes the expectation is a white elephant, unspoken but suffocatingly present; other times, it’s an off-the-record conversation that de-prioritizes a young dancer’s medical expenses to, instead, focus on missing an entire home season run. Because we’ve been conditioned into a scarcity mindset, we dare not risk our performance opportunities or let down our castmates over a toe we can no longer feel or an ankle we feel all too much.

Like gymnastics, dance can be dangerous and requires us to be at our best. The irony of performing at all costs is that when we force ourselves to perform while injured or unwell, we are not at our best. Once, while lifting my former colleague during a performance, for example, I was so distraught from a pre-performance dressing room incident that I crashed us into the side lights and bruised her sternum.

Let me be clear that I am all for pulling through for your team. My entire career has been one gigantic team effort; I owe everything to collaboration, mutual aid and the kindness and generosity of others.

But here’s the thing: The most important part of a team effort is supporting a teammate when they’re down. A team effort should not be detrimental to your health (physical, mental or emotional), regardless of whether you are dispensing or receiving aid. And you should never feel shame for needing support.

Dancers are well-suited for this culture of team care. We build our careers on being adaptable! We absolutely can—and should—adapt to support each other’s access and health needs, and doing so does not hurt our art, but elevate it. The U.S. women’s gymnastics team supported Biles and adapted to her health needs, and they’ve won Olympic medals in the process.

True, this was possible because Biles advocated for herself and trusted her team, but she was also only able to do so because because, as she said in the news-conference transcript posted on NPR, she “had the correct people around [her] to do that.” And this is another lesson for the dance world.

The onus of “self”-care is often easily misplaced onto the individual dancer. However, as our field continues shifting in the wake of 2020, companies can cultivate team care as a collective, rather than solely individual, responsibility.

Directors create a culture of empowerment—not scarcity—that encourages dancers to speak up, makes them feel heard and takes action on their behalf. Biles was empowered to advocate for herself because the team built a culture of trust and care. It is a “both/and” responsibility. Replicated in the dance world, the potential dividends could extend beyond self-care to other social justice issues facing our field. But if we don’t allow our dancers to do what Biles did, then our love and praise for her rings hollow.

Biles and Team USA have significantly impacted the gymnastics community and made us question our values as Olympic spectators. Last week, the 24-year-old G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time) may have felt “the weight of the world on [her] shoulders,” but now, the weight of Biles, Team USA and their radical example are on the dance world’s shoulders.