How “Mean Girls” Dancer Stephanie Bissonette Survived Cancer and Made it Back to Broadway

Last year, Broadway dancer Stephanie Bissonette was diagnosed with a brain tumor—but she didn’t let it keep her offstage for long.

(As told to Amanda Sherwin)

2018 was the best year of my life: I opened Mean Girls and made my Broadway debut. I got to work with Casey Nicholaw and Tina Fey, people I had admired for so long. We did all of these wonderful appearances, from “Late Night with Seth Meyers” to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and even the Tony Awards. All these dreams I’ve had my whole life were coming to fruition thanks to this one show.

It was the end of January 2019, and as I landed an aerial during my seventh show of the week, I felt something weird. I was more unbalanced than usual, and for a second the room spun. Luckily, I collected myself and finished the rest of the show with no problem. But I’d been doing that tumbling pass since I was 15, and nothing like that had ever happened before. As dancers, we’re so hyperaware of our bodies that I knew something was off. A few days later after a whirlwind of visits to the doctor and ER, I was told that there was in fact a tumor on my cerebellum, and that’s why my balance was off and I felt dizzy.

The following Monday, my surgeon removed the tumor. I was in surgery for six hours, and woke up sore and groggy, with IVs in every limb.

After that, I was very sick. It was hard to sit up, and I would often throw up from all the medications and physical trauma of the surgery. A lot of the Mean Girls cast came to visit me. The day before I was about to leave, the next blow came. I learned that the tumor was in fact cancerous, a kind called medulloblastoma. It’s a tumor usually found in small children, so I was a very rare case. My doctor told me that I would need to undergo radiation for six weeks.

I was devastated. I cried in that room with my parents for a long time. It wasn’t even because of the radiation. I was mainly upset because I couldn’t go back to work.

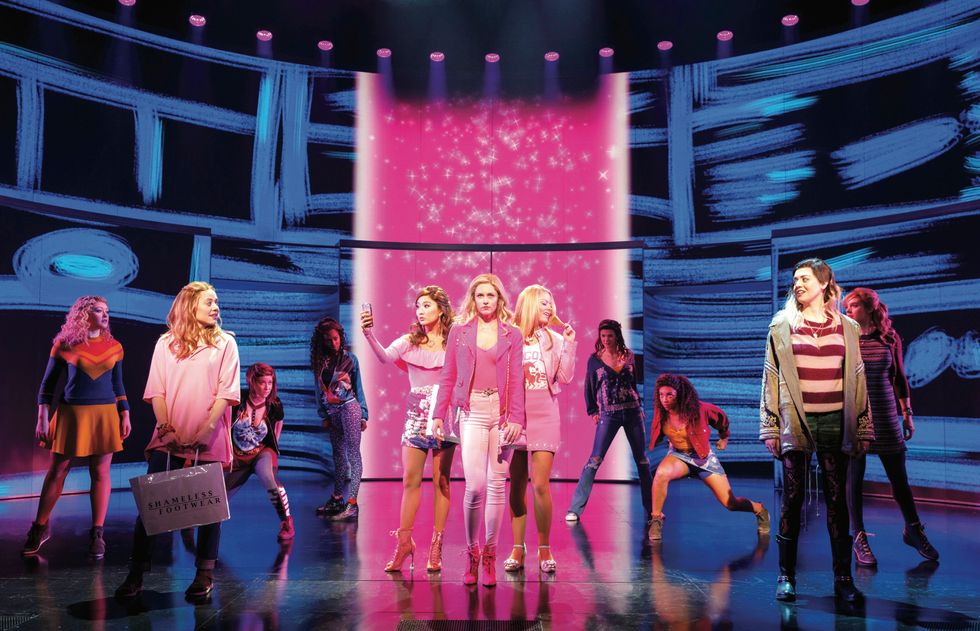

Mean Girls (Joan Marcus, courtesy Mean Girls Production))

When you work and train for something for 28 years, and you finally make it, to have it all taken away is very, very hard. But, I’m lucky to be here at all. This show and my dance training saved my life. My doctors said it’s incredible that I was able to function as a professional athlete with the tumor. If 18-year-old Stephanie had decided to be a lawyer like she was going to, I could’ve been sitting at a desk, thinking this was all just a headache. Thanks to me dancing on tables and kicking my face every day, I was able to identify the tumor so early that I’m now a survivor.

The road to recovery was, and is, frustrating. One day, I would feel like a normal person again, and then the next, the whole world would come crashing down. The thought “I’m never going to get better” kept repeating in my head, but I fought to keep a positive outlook. There were times when I would be coming home from radiation so upset, and then “I See Stars,” the finale song of the show, would come on my phone. I would listen, and try to picture myself back onstage with my friends.

What else is a workaholic to do when the only work to be done is healing?

Before, even if I was injured, I would do everything I could to push through, as dancers often do. This was the first time I’ve been forced to be still, and it was the hardest thing I had to do in my life. I couldn’t fathom another week of me just walking to the grocery store and back. I had to confront my fear of falling behind, something I’ve been afraid of my whole life, and remind myself that resting was necessary for longevity in my career. It definitely helped me gain perspective.

I finished radiation in April 2019, and by July, I started taking a dance class every couple days. Before, I considered myself a turner—I could whip out four pirouettes easily. When I returned to the studio, however, even just rolling down my spine and back up could make me lightheaded. It’s been a slow and humbling healing process, waiting for my brain to readjust to doing all these crazy things that dancers do. I focused on what I could in the meantime, which was style, musicality, isolations—anything that didn’t involve turning. I also found that I connected to my artistry a lot more deeply. When you’re younger, you think you’re invincible and can get through anything. Then, you go through something like this and realize it’s alright to cry. I’ve learned that there’s a difference between being weak and being vulnerable, and my emotions are a lot more accessible, which will be a wonderful thing for me to pull from as a performer.

The hardest part was that I’ve been dancing at Broadway Dance Center for 10 years, so I know everybody there. There was a big feeling of embarrassment coming back. I didn’t want to seem weak or not on my game in front of everyone in the industry. But I’m so grateful to my teachers, especially Sheila Barker, who stuck with me and helped rebuild me as a dancer. This whole experience has made me grateful for the power of the NYC theater community. We come from all over the world to pursue our dreams, so when our “real” families can’t be near, we support each other. There’s nothing more touching than having a community you admire come around and say “We’re rooting for you.”

After months and months, I finally set a date to reenter the show: October 3rd, aka Mean Girls day, of course. I had a couple vocal and dance rehearsals to get up to speed on aspects of the show that have changed, did my put-in rehearsal the day of, and I went in that night. There was so much anticipation and stress leading up to that moment—it was bigger than my Broadway debut, bigger than anything that’s happened to me. When we finally got to the finale, “I See Stars,” Erika Henningsen, who plays Cady, surprised me by throwing me a piece of her crown, which isn’t part of my track at all. Of course, it slipped through my fingers and fell on the ground. It felt like such a symbol of my life for all of us to laugh onstage as I picked up the piece and just kept going.

Mean Girls (Joan Marcus, courtesy Mean Girls Production)

When I got offstage after bows, I couldn’t stop crying. My whole first week back was emotional, but my cast made me feel so special and supported. And every show gets easier. I’m still struggling with symptoms, but now I’m able to work through them. I’m so thankful to be back in the show, and will continue to train and get stronger. My goals for dance haven’t changed either—I want to do it all, from dancing in more Broadway shows, to teaching and choreographing.

For anyone else going through this, keep your head up. If you’re unable to do your craft because of an injury or illness, find the things that make you happy outside of it. Find the joy in a cup of coffee with a friend, or in going to the movies. Know that if you have enough passion, you can push past anything. There’s a resilience in performers, and that training my whole life has definitely helped me through this.

The best connections you make in life are with humans, not jobs. I’m thankful for the people who lift me up in my darkest hour; who believe in me when I can’t; who insist when my faith is shaken. The family and friends who are there, unconditionally, always—whether you are unemployed doing puzzles at your kitchen table, or taking a bow on Broadway.