Why We Can’t Take Our Eyes Off of Taylor Stanley

In a studio high above Lincoln Center, Taylor Stanley is rehearsing a solo from Jerome Robbins’ Opus 19/The Dreamer. As the pianist plays Prokofiev’s plangent melody, Stanley begins to move, his arms forming crisp, clean lines while his upper body twists and melts from one position to the next.

All you see is intention and arrival, without a residue of superfluous movement. The ballet seems to depict a man searching for something, struggling against forces within himself. Stanley doesn’t oversell the struggle—in fact he’s quite low-key—but the clarity with which he executes the choreography draws you in.

There are dancers who externalize ideas and others who fascinate you with their interiority. Stanley is the latter. “I love that Taylor is shy, even onstage,” says choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, who coached him in his Namouna, A Grand Divertissement last year. “He doesn’t exhibit his soul, but you know it’s there.”

Namouna

and Opus 19 are only two of a smattering of new ballets Stanley has debuted in over the last year. It was a trying time for the company. First, the longtime director, Peter Martins, left under a cloud of accusations of misconduct. Then, three male principals were also accused of misconduct—one resigned, and two were fired, though later reinstated after arbitration.

The sudden rupture was unsteadying, admits Stanley, but also, in a way, liberating. “Along with that feeling of absence and change,” he says, “there’s a sense of responsibility that we’re all taking as individuals.”

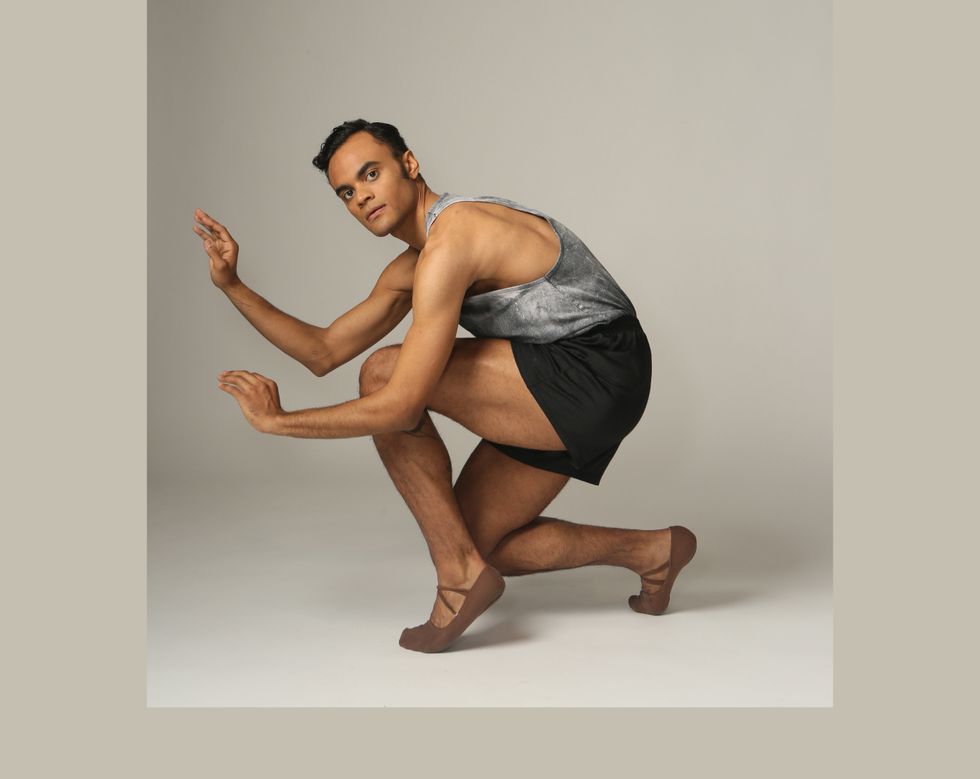

If you had to pick one galvanizing moment, it would be the premiere of Kyle Abraham’s The Runaway last September. In two solos, one set to quiet music by Nico Muhly and the other to Kanye West and Jay-Z, Stanley stopped time, folding and unfolding his body in that shape-shifting way he has, molding the air around him with his arms, then rippling his shoulders with sinuous, elegant ease.

“He has this mysterious center, rich and layered,” says Abraham. “He constantly wanted to push harder and further.”

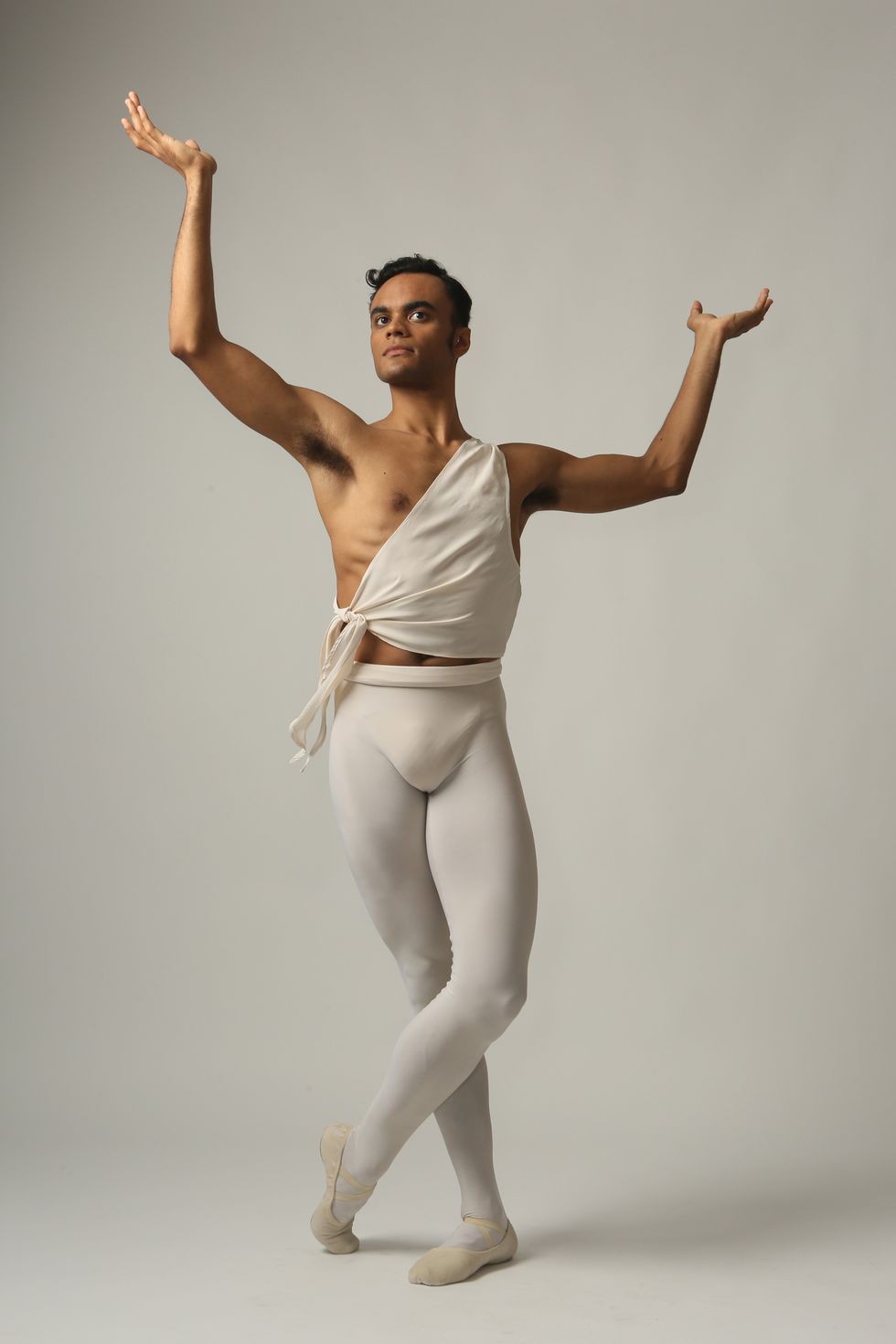

And then there is Apollo, one of the most coveted and complex roles in the male repertory, and one Stanley never imagined he would get to dance. In part, because all the previous Apollos at NYCB have been white, save one: Craig Hall, who got to dance it exactly once. Stanley is mixed-race and fine-boned, neither particularly tall nor particularly commanding, unlike most of the Apollos who have preceded him.

“His hang-up at first,” says Hall, who coached him, “was feeling ‘I’m not a classical dancer in a lot of people’s minds, so I have to be very classical.’ A lot of the time we were talking about making it a little rawer.”

Stanley had to find his own path through the ballet. “I started thinking about the three muses as teachers rather than in a romantic relationship,” he says. “A lot of my friendships are with women, and those women have raised me, almost. So I pictured each muse as one of those friends.”

His interpretation was infused with great delicacy, not a quality one tends to associate with this ballet. At one point during his debut, he turned to his three counterparts with a shy, almost grateful smile.

It was a beautiful moment, because it felt real. Other dancers remark on this ability to connect onstage. Lauren Lovette remembers dancing Romeo + Juliet with him: “Never for a minute did I feel he wasn’t completely in love with me,” she says.

She drew upon this quality for a pas de deux she created for him and Preston Chamblee in 2017’s Not Our Fate. The duet was part of a trend toward representing a less narrow view of love, gender and partnering in ballet. And again, Stanley was just right for it—his dancing has been described as having a “gender-fluid allure,” one that doesn’t conform to a prescribed definition of “masculine” dancing.

He is certainly not the first to explore this terrain. Over its history, ballet has periodically reexamined ideas of masculinity, from the dignified but un-virtuosic danseurs nobles of Petipa to the exoticism of Nijinsky and the gender-bending sexuality of Maurice Béjart’s ballets.

Stanley’s approach, though, feels more internal, focused on getting closer to his own natural movement quality. He recalls feeling out of place while training at The Rock School for Dance Education in Philadelphia: “I didn’t feel super-connected to the male steps and the male bravura you learn in men’s class,” he explains.

Things improved once he came to the School of American Ballet for his final year of training. “I think that coming here you become so refined, which was good for me. I didn’t have to fit into this manly thing.”

To that refinement he has recently added the body-awareness and fluidity of Gaga, a movement language created by Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin. Last August, Stanley took part in a summer intensive in Tel Aviv led by Naharin and dancers from Batsheva Dance Company.

“I felt a lot of inspiration, and a lot of unbuckling,” he says. “You start to think about your bones inside of your flesh, and about finding the ability to float inside your skin.” He has been trying to apply these ideas to the more formal structure of ballet.

The experience intrigued him enough that he auditioned for Batsheva—The Young Ensemble this past winter, though he didn’t get in. (“I had to check the ego,” he says with a laugh.) The restless part of him is haunted by the possibility that there might be another reality out there that might fulfill him more.

“There’s something in me that needs to be fed,” he says, “and doing that audition was part of understanding what is the food that I need.”

In the past, that search involved coming out as a gay man, at 21. (He’s now 28.) Stanley comes from a religious background and feared disappointing his family, with whom he remains very close. He even tried conversion therapy for a year, a process that, unsurprisingly, left psychic scars.

He still struggles with self-doubt, though mostly, these days, it’s focused on his dancing. “It all trickles down from shame about being a good person, a good son,” he says.

The wounds are not easily healed. “He’s extremely hard on himself,” says Hall, “and never gives himself enough credit.” It was clear even in that Opus 19 rehearsal. Stanley was less satisfied with his dancing than the coach was, and, at one point, turned away from the mirror to avoid its scrutiny.

The search, now, is focused on finding a form of expression that feels honest. Part of the answer may come at NYCB, where a new team, composed of Jonathan Stafford and Wendy Whelan, has taken the reins. Whelan, especially, has been deeply involved in contemporary dance since retiring from NYCB in 2014. Stanley is hoping her interests will rub off on the company. There is a long list of choreographers, including Naharin, William Forsythe, Crystal Pite and Jirˇí Kylián, whose work he would like to dance. “I think we would kill it. And it would shape our bodies and give us more information about how to do the other things.”

With the uncertainty of the last year has come a greater self-knowledge. “Before all of this,” Stanley says, “I felt kind of asleep. But we’ve really had to go back and look at ourselves. How do I feel about myself? How can I reinvent myself?” The search continues.