The New Girl: Olga Smirnova

Participating in new work is a rare luxury at the Bolshoi, yet this past April, just two days after starring in the live HD broadcast of Marco Spada, Olga Smirnova found herself experimenting for the first time in the Bolshoi’s Studio 1. Oblivious to the chatter around her, she looked intently at choreographer Jean-Christophe Maillot as she parsed the first steps of his new Taming of the Shrew with quiet focus, lending them amplitude and a swanlike articulation. Slowly, she ventured new accents for her character, Bianca—and broke into a rapt smile when Maillot screamed his approval. “There is a softness to her, and she has no preconceptions,” he says of Smirnova. “She uses every detail, every piece of information I give her.”

Since joining the Bolshoi as an outsider from the Vaganova Academy three short seasons ago, Smirnova has had critics and audiences alternately abuzz and awestruck. At just 22, she is fast making her mark at the crossroads of the St. Petersburg and Moscow traditions, her pristine clarity of movement melding seamlessly with the dramatic emphasis Moscow has long cultivated. Her “Diamonds” revealed an expansive, spellbinding young queen; her gift for tragedy, meanwhile, has found telling vehicles in Onegin and Lady of the Camellias.

Smirnova’s career has skyrocketed, making her, at just 22, one of the Bolshoi’s biggest draws.

Photo by Nathan Sayers.

To get to this point, an unlikely number of stars had to align. Deemed the “physically perfect instrument of her art form” by English critic Luke Jennings, the revelatory harmony of Smirnova’s lines speaks to the ruthless Vaganova training. Ballet in Russia is also a mental game, however. Self-possessed beyond her years, Smirnova has reaped the rewards of what she deems the most difficult decision of her life: refusing the Mariinsky and entrusting her career to Bolshoi director Sergei Filin.

Her choice reflects a seismic shift in Russian ballet, where ballerinas used to grow up and old in the company they were trained to join. The Mariinsky was always the logical step for Smirnova, a native of St. Petersburg. Her music-loving family had no connection to ballet: Her mother was an engineer, but when she noticed that Smirnova showed potential in dance, she decided to take her to the Vaganova Academy.

Smirnova in Onegin.

Photo by Damir Yusupov.

Smirnova was accepted immediately, at age 10, and her talent didn’t go unnoticed. Singled out as a leader for her age group early on, she found herself front and center in class, as is the Vaganova tradition, and faced with the burden of expectations. “It’s huge psychological pressure for a kid,” she explains matter-of-factly. “Others were allowed to make mistakes, but if I did the teacher would ask me: How could you? As they say, it’s not easy to get to the top, but it’s much harder to stay there.” Less flexible than her classmates, she took extra weekend gymnastics classes to achieve the sky-high extensions now standard in Russia.

By the time she completed her training in 2011, Smirnova’s reputation as a prodigy preceded her. Bolshoi director Sergei Filin made the trip to St. Petersburg to see her graduation performance, and soon the young dancer found herself with competing offers of a soloist position from the rival St. Petersburg and Moscow companies.

Joining the Bolshoi wasn’t her initial choice, Smirnova says. Instead, she tentatively started to work at the Mariinsky without signing her contract, but found the atmosphere uninviting. “I felt the artistic director and the teachers weren’t interested in nurturing new, young ballerinas. But Filin came up with a very logical plan. He wanted to involve me in the Bolshoi repertoire step by step, starting with variations, Queen of the Dryads, Myrtha—very important roles to prepare you.”

With Semyon Chudin in “Diamonds.”

Photo by E. Fetisova, Courtesy Bolshoi.

Filin kept his word, and Smirnova’s move reasserted the changing balance of power in Russian ballet: While the Mariinsky’s aura and attractiveness have faded over the past decade, the Bolshoi, for all its intrigue and scandals, remains at the top of its artistic game. Loneliness was inevitably a challenge for the young dancer, but the repertoire kept her fulfilled. Variations soon gave way to carefully chosen principal parts; in addition to debuts in La Bayadère and The Pharaoh’s Daughter, she was cast by The Balanchine Trust in the Bolshoi premiere of “Diamonds” in her first season.

Absorbing the Bolshoi style proved Smirnova’s most pressing task. While a growing number of Vaganova-trained dancers work in the company (including another Filin protégée, Evgenia Obraztsova), clear differences remain. Smirnova praises the purity of the Vaganova technique, but says Moscow has helped her develop endurance and strength under the tutelage of her coach, Marina Kondratieva.

The bold acting tradition was another challenge. Her hunger for new experiences and love of theater have helped her fit in, but Smirnova is still fine-tuning her approach. She reviews videos of her performances with her coach, critiquing and revising her choices. “When I first came here, everybody said: Here is another ballerina from St. Petersburg who will be cold and unemotional,” she remembers. “I didn’t understand what they meant—should you be crazy onstage? What’s the limit? It’s still an open question for me.”

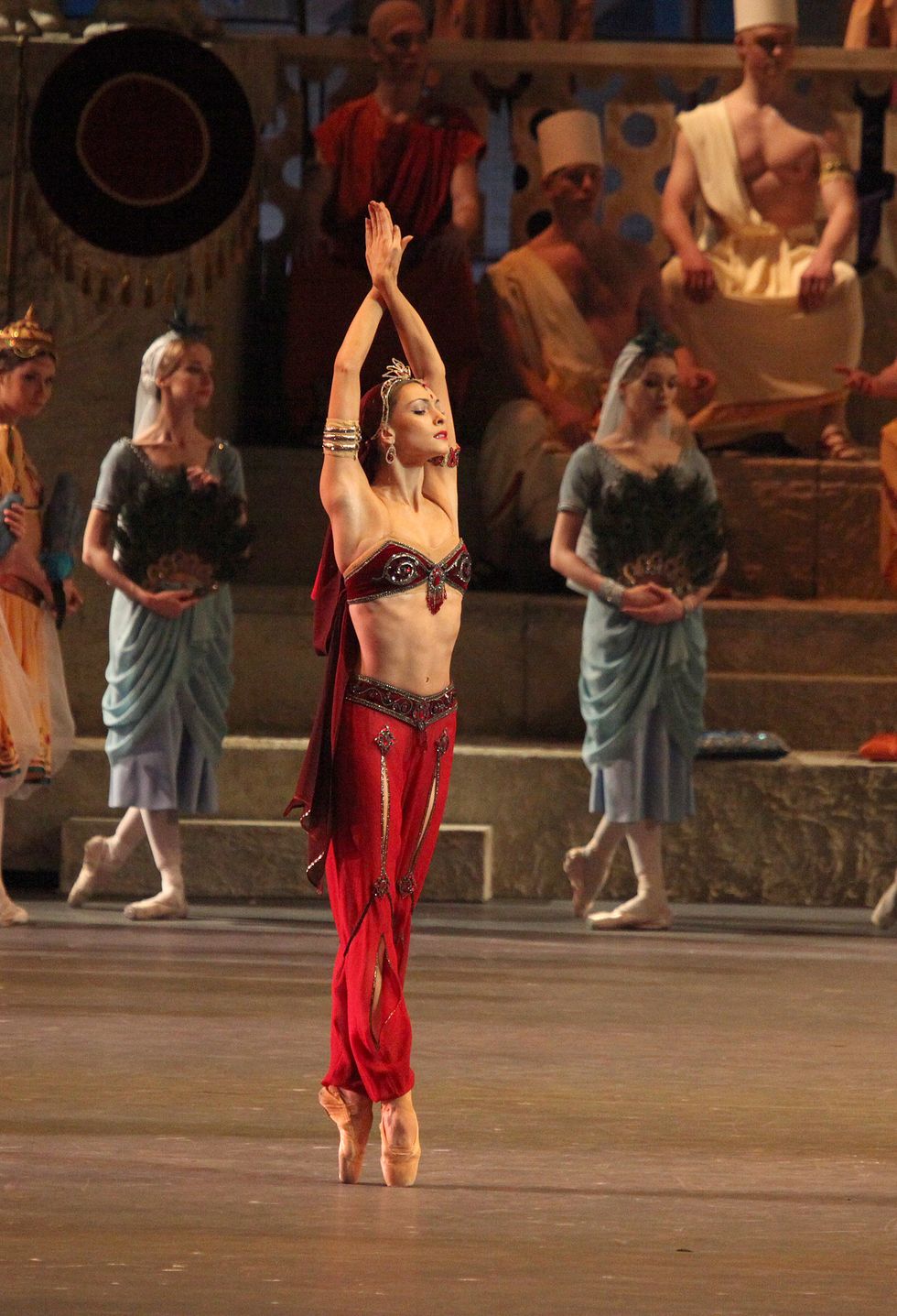

A passionate Nikiya in La Bayadère.

Photo by Damir Yusupov, Courtesy Bolshoi.

Despite her doubts, she has quickly become the face of the repertoire brought in by Filin. A feature of his directorship has been narrative ballets no Russian company had previously taken on, including Cranko’s Onegin and Neumeier’s Lady of the Camellias, and his young protégée has run with the opportunity. When we meet, a few days after her second Lady, she is visibly spent. “These ballets take a piece of your soul,” she explains. “It’s similar to the feelings you have after finishing a huge book. You live with the characters, and you feel an emptiness after them.”

Smirnova’s onstage maturity is mirrored by her levelheaded response to the pressure cooker she has found herself in. At the trial following Filin’s acid attack, in an attempt to smear him, the defendants accused him of having an affair with Smirnova, an episode she has learned to laugh off.

The attack aside, Smirnova deems the atmosphere of intense competition at the Bolshoi the continuation of what she experienced at the Vaganova Academy. “You just have to prove that you’re dancing a role because you’re the best at that point. It’s good, because it keeps you on your toes.” Cliché or not, she is her own biggest critic, believing that she danced Odette/Odile too early, describing her interpretation as “too raw. I still don’t truly, fully understand the role.”

Photo by E. Fetisova, Courtesy Bolshoi.

Lately, she has found new roots in Moscow: Last summer, she married the son of Filin’s former advisor, Dilyara Timergazina, in an Orthodox ceremony. Her husband, who works in finance, is her support system. “He completely understands that my life is in the theater now, and he gives me the strength to perform.”

There is an uncanny purpose about Smirnova, but it would be a mistake to take her for a diva. “You can see that she doesn’t position herself according to a title, a status,” says Maillot. “She just asks: Can I do that, how can I do it, what can I learn?” She is on track to be one of the defining dancers of her generation, but her path may prove slightly different from other Russian superstars who have forged their own international brand away from company ties. “Everything I have done was given to me by the theater,” she muses. “The Bolshoi is my home now, and for an artist, it’s very important to have a home.”

Laura Cappelle is a dance writer based in Paris.