The Toll of Touring: Dealing With the Hidden Mental Health Challenges

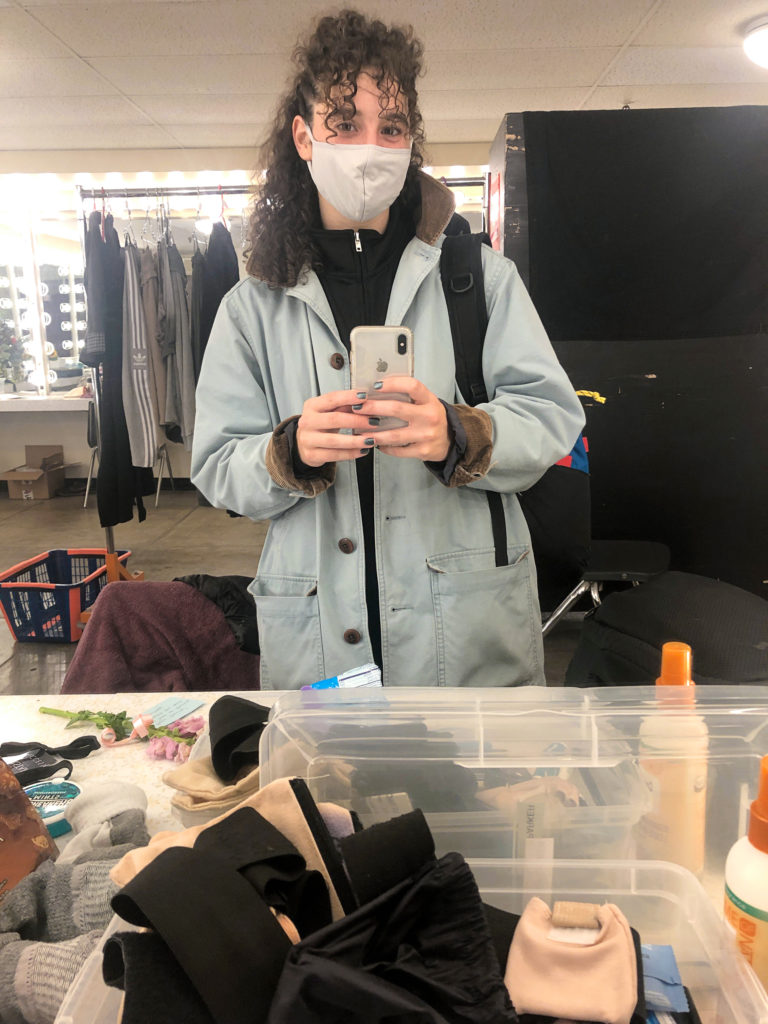

It was sometime in December. I looked around my sparse Airbnb in Toronto, trying to focus on the few personal touches I’d added to an otherwise unfamiliar space. A framed photo of me and my partner on the nightstand, my own pillow on the bed, a stack of my journals and books on the desk in the corner. There was one hour until I had to walk to the theater to get ready for the show, and I didn’t want to do it.

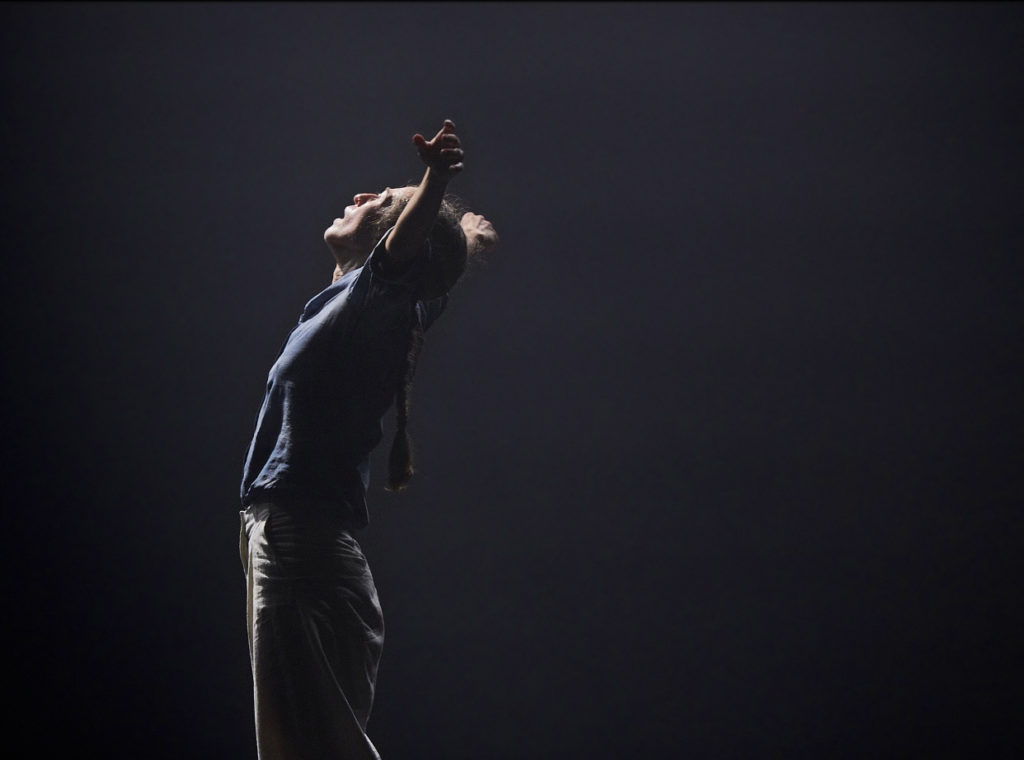

Sitting on a gray couch looking out at a gray sky, anxiety flared as I tried to understand a brain rattled by conflicting thoughts. Zoomed out, I had every reason to be happy. I was on the national tour of Jesus Christ Superstar, performing a dream dance role eight times a week. I was making good money. I was part of a company and show I adored and respected and was working with people who adored and respected me back. I had returned to performing full-time after an 18-month shutdown and was traveling to a new city every few weeks.

But zoomed in, there were deeper layers. I missed my partner and our home in Brooklyn. It was the first time in my 32 years I wouldn’t be spending the holidays with my family. I felt alone. I was tired of packing and unpacking my suitcase, of wearing the same clothes over and over, of never knowing whether the shower at that week’s theater would have hot water or not. I was tired of the daily COVID-19 protocols, the fluctuating masking and vaccination rates in different cities, the waves of positive tests and canceled shows, and the looming fear of another industry-wide shutdown.

I was both immensely grateful and depressed at the same time. And entertaining even the slightest negative thought when I knew so many dancers would give anything to be in my position was leading me into deep guilt.

Full-time touring as a dancer is both a wonderfully prosperous adventure and an exhaustingly difficult job. Packing up your home and living on the road while navigating an industry already plagued by high highs and low lows is a recipe for mental health challenges. And now with the additional weight of COVID stresses, many dancers are craving honest conversations and tangible resources to help gain stability in a life defined by change.

The glory of touring arises from the fact that we’re consistently dropped into new locations, and are paid to be there, doing what we love. We may be in a city for anywhere from two days to five months before moving on to the next one. “It’s like cracking open the door of a new place,” says Marlon Feliz, a dancer with Pilobolus. “It offers you a taste of local culture and a small insight into different worlds.”

While most touring artists appreciate that thrill, it also automatically removes us from our home bases for long stretches of time. We’re no longer sleeping in our own beds, surrounded by our personal things and maintaining our well-crafted routines. “You have to constantly adjust to the physical space that’s available and you never get to fully settle in,” says Feliz. It’s harder to relax post-show when an endless string of hotel rooms offers little comfort.

Adapting to ever-changing environments can cause different responses. “If you’re always accepting new situations, new places, new habits, new patterns, and you don’t have all of your creature comforts, the only thing you can rely on is your inner stability, which can be really empowering,” says Rachel Fallon, a dancer who’s toured internationally with the Hofesh Shechter Company for five years. “But you could also cope by becoming numb to it all and shutting off. The constant imbalance can make you enter survival mode instead of actually being present.”

More difficult than the separation from physical comforts is the disconnection from loved ones. Our show companies become our families, which is beautiful in its own way. But being apart from spouses and best friends creates a particular kind of loneliness that always buzzes in the background. FaceTime catch-ups aren’t always convenient across time zones and schedules, and, as Feliz says, “sometimes, no matter how hard they try, friends and family can’t fully understand how challenging and personal it all is.”

Dr. Miriam Rowan, a clinical psychologist and an instructor at Harvard Medical School who now works with performing artists and athletes following her career with San Francisco Ballet, understands the dichotomy between the image of touring and how it can actually manifest for those living it day to day. “You can be discontent with certain aspects of an experience and also be wildly overjoyed to be a part of it,” she says. “And outside responses of ‘Your life is amazing and you’re doing what everybody wants to do’ can be extremely invalidating. Then you internalize that invalidation and it makes you feel worse.”

For me, sometimes the choreography can be therapeutic. I can release stress through movement and come out the other side feeling lighter. Luckily I am in a show with room for that type of physicality. But other times, when my brain is somewhere else, it can lead to missteps and injuries, which then in turn can weaken my mental stamina.

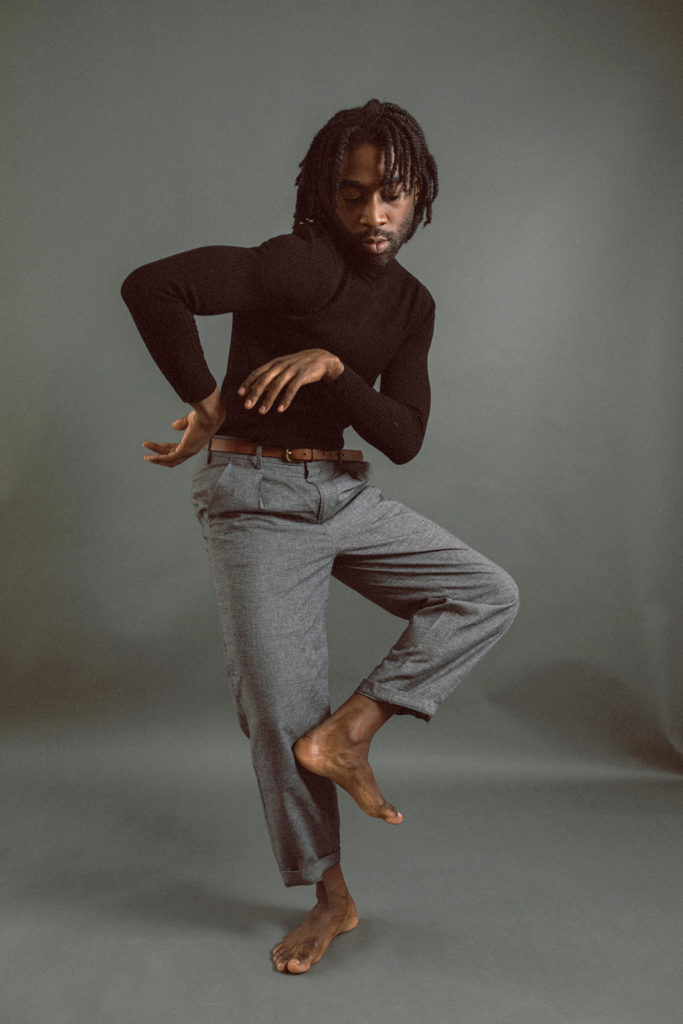

“You realize your muscles respond to your thoughts and emotions,” says Chalvar Monteiro, a dancer in his seventh year with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. “So much goes into live, touring theater. It’s more than just learning steps and doing them. The teamwork elements, managing personalities, finding time to eat and connect with your family…it all affects your performance.”

Although touring dancers do have free hours on days without rehearsals, and every now and then a full day off without travel, the job is essentially full-time, all the time. And an endless cycle of shows and airports can evolve into burnout.

Adrianne Chu, an ensemble member in the Lion King Rafiki tour, knows how that can lead to problems. “With all the puppetry in this show, you definitely need physical strength, but your brain also has to be sharp,” she says. “With the huge amount of people onstage and backstage, you always have to be on high alert. So if you’re going through any form of mental exhaustion, it will affect everyone on the job.”

It’s usually easy for producers and managers to grasp the concept of dancers needing physical therapy on tour to keep their bodies in top performance shape, but the emotional support required is not regularly understood. The “push through” mentality has long been common in dance, and sometimes dancers are unfortunately viewed as bodies rather than well-rounded humans. Emphasis tends to be placed on our physical abilities, and stigmas and budget cuts often get in the way of providing solutions to something deemed lower on the priority list.

Most touring dancers I’ve spoken with, myself included, feel comfortable sharing their mental health struggles with castmates, but not bringing them to leadership for fear of appearing weak or unfit for the job. The hushed conversations happen behind closed hotel and dressing room doors. And while private discussions with a trusted friend definitely offer their own kind of safety, most of us are not qualified to give the kind of guidance needed. Some dancers hire virtual therapists on their own dime, but most agree that a regular company-provided check-in with an objective professional could provide a grounding foundation throughout the cast. “There’s so much we could benefit from by having a place to lay down our burdens,” says Monteiro.

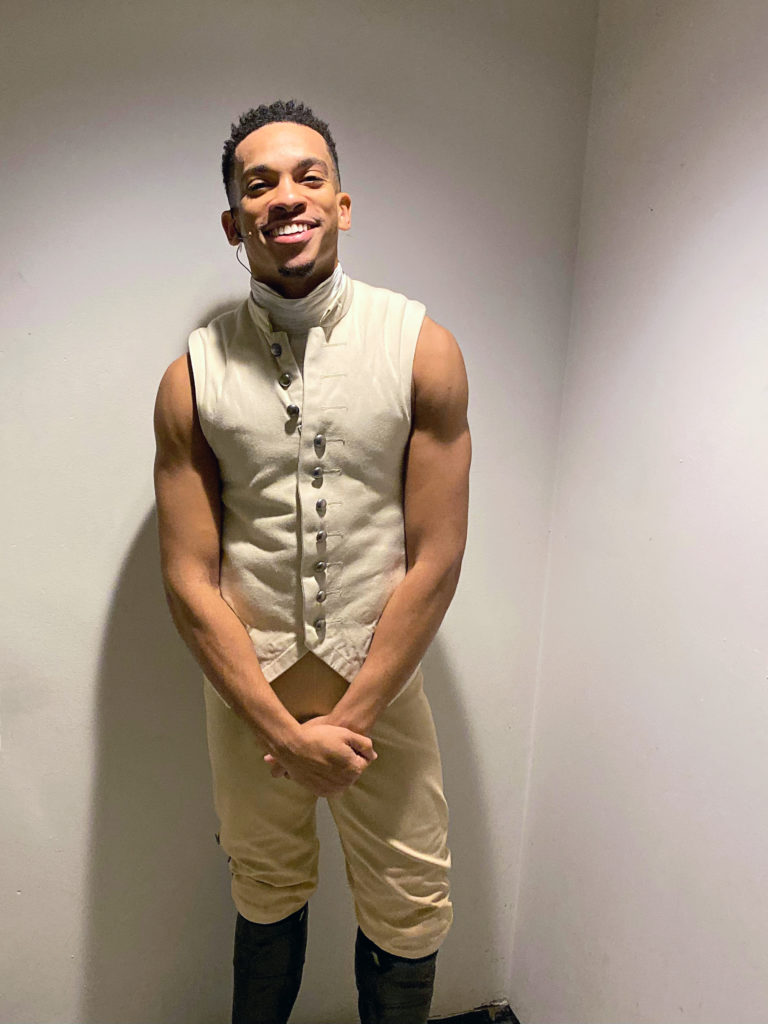

Requesting mental health days often feels taboo, causing dancers to bottle their feelings and explode or crash later on. “There have been many times when I was near an anxiety attack, but I still did the show,” says Gabe Hyman of the Hamilton Philip tour. “Once I recognized it was an option to take the day for myself, and felt supported by my stage management team to do that, I was able to get out of that tough place a lot quicker.”

A day off isn’t always the right solution for everyone, though. “Sure, we all go through similar things collectively,” says Hyman. “But as a gay, Black male, my experience on tour and in the workspace could be very different than yours. Everything we’re dealing with is so nuanced.”

Luckily, Rowan feels things are starting to move in the right direction, thanks to a larger cultural shift enabling creatives to reframe struggles as a mental health issue, as opposed to a bad attitude or laziness. “Historically there hasn’t been substantial space for those conversations,” she says. “Emotional struggles have at times been considered signs of weakness in these competitive performing arts pursuits, but now we’re identifying that they’re not weaknesses, they are just parts of life.”

Establishing readily available resources that value emotional as much as physical wellness would set up a comprehensive care system to make life on the road more manageable. Once those systems are in place, it will be up to dancers to become okay with vulnerability. Like Fallon says, “I’m used to holding on so tightly, trying to maintain control of everything. But I’ve now realized that’s not necessarily strength. Strength is often letting go and allowing myself to accept whatever it is I feel in that moment.”

Tips for Maintaining Balance on the Road

From touring dancers:

• Incorporate quiet daily practices, like meditation, journaling and reading.

• Always carve out alone time.

• Take long, meandering walks around the area.

• Carry small, decorative objects that can help warm up a hotel room.

• Try virtual dance or exercise classes to move your body in a different way.

• Schedule weekly catch-ups with friends and family.

From clinical psychologist Dr. Miriam Rowan:

• Keep a log of your basic patterns—meals, sleeping, alcohol consumption, etc. When one is off, it can be a sign that something deeper is not right. Writing them down helps create mindfulness.

• Become aware of best “sleep hygiene” practices, like not using your bed in the daytime for watching TV or making phone calls.

• Focus on self-compassion. Create a soothing, calming orientation towards yourself physically and intellectually. Try yin yoga and breathing practices that allow the body to achieve a deep state of relaxation.