"The Steps Are Gravy," Says Tony Winner Christopher Gattelli on Choreographing for Broadway

The 20-somethings doing Broadway Dance Lab’s first-ever Choreography Summer Intensive ended their recent tour of Lincoln Center’s New York Public Library for the Performing Arts with something special. In the seminar room, Tony-winning choreographer Christopher Gattelli awaited them with a conference table laden with Broadway treasures from the library’s collection. Decades-old original sketches and black-and-white production photos from My Fair Lady, The King and I and South Pacific served as visual aids for Gattelli’s discussion of these shows’ Lincoln Center Theater revivals, as well as My Fair Lady‘s 2016 60th-anniversary production at the Sydney Opera House, directed by the original Eliza, Julie Andrews.

Prodded by BDL founder Josh Prince, Gattelli talked about tackling those three musical theater classics and the art of Broadway choreography in general. Here are some highlights, edited and annotated for clarity.

Doing My Fair Lady at Lincoln Center

“The hardest thing was that I had done it. It was kind of living with ghosts. When I did ‘Get Me to the Church’ for Julie, it stopped the show. [drawn-out groan] It was, ‘How do I do that again?’ [growl]… When we did it in Sydney, the Doolittle was close to 80. So my goal was also to take care of him. I built the number where he wouldn’t have to move too much. Norbert [Leo Butz] was the opposite—he was jumping into splits, he couldn’t do enough for the number. It was a super lesson—trust your collaborators, your performers, look at what you’re given.”

The current production of My Fair Lady features a rousing “Get Me to the Church on Time,” with Norbert Leo Butz jumping into splits. Photo by Joan Marcus, Courtesy Lincoln Center Theatre.

New Director, New Direction

South Pacific

was Gattelli’s first collaboration with director Barlett Sher. “In my interview with him, he said, ‘Oh, I don’t care about the steps. I don’t care about preproduction.’ And that’s all I ever did! T’s were crossed, i’s were dotted—I’d go in with 85 to 95 percent done. [When Bart said,] ‘We just make it up in the room,’ I was like, ‘What?’ It was the greatest gift ever, working that production. He did teach me that if you really do your homework, and if you really do your research, all of a sudden, it will come out. He opened my eyes to—wow!—you don’t have to have everything answered. You can make mistakes in front of the cast. You can come back and fix it the next day after you think on it.”

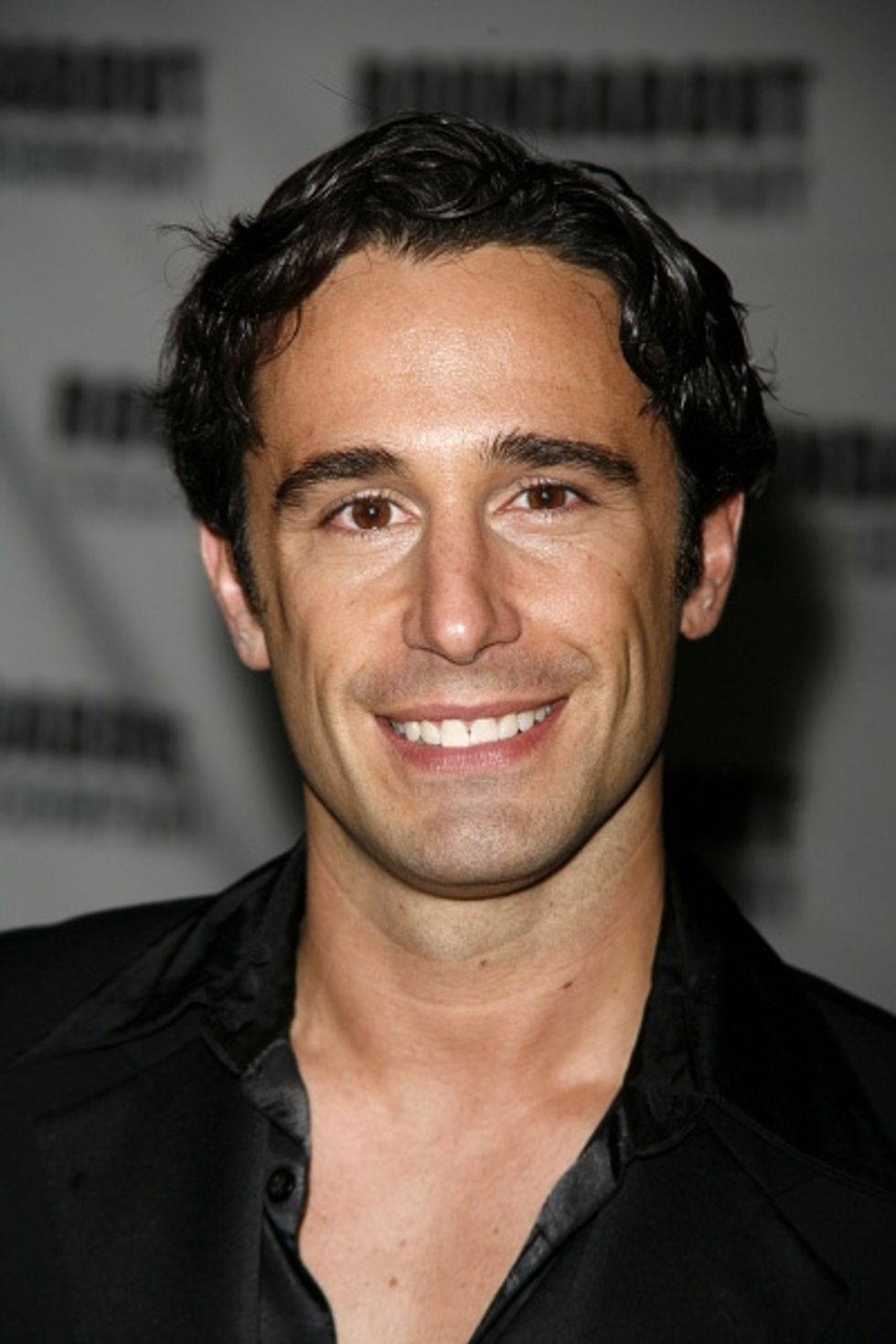

Bartlett Sher taught Christopher Gattelli (picture here) a new way of working. Photo by Joseph Marzullo, Courtesy Boneau/Bryan-Brown.

Bartlett Sher taught Christopher Gattelli (picture here) a new way of working. Photo by Joseph Marzullo, Courtesy Boneau/Bryan-Brown.

It’s All About the Story, Story, Story

When Gattelli was working on the South Pacific number “I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair,” Bart kept saying, “I don’t buy it. I don’t buy it.” “Because dramatically,” Gattelli says, “it wasn’t a piece that necessarily moved the story forward. It moved her spirit forward. So I had to stop making it entertaining. It was false, because I wasn’t trusting to let their spirits take over. I was just trying to make it fun and sell it.”

Sometimes a Revival Is Really an Original, Tweaked

For The King and I, Sher and Gattelli decided to retain Jerome Robbins’ original choreography for the show’s second-act ballet, “The Small House of Uncle Thomas.” “We knew that the ballet is this jewel—it’s brilliant. Without that, I don’t know that I would have accepted the job—I wouldn’t know what to do with it. What Bart did say was, ‘We’ll keep it, but we have to make it work for our production.’ He wanted to give the audience a sense of what Anna was going through, that the king is a dangerous man. He wanted that kind of feel in the ballet as well, so that it felt aggressive. Everything had this extra hold, and stiffness, and tension.”

The Tony-Winning Newspaper Dance in Newsies

“It wasn’t to be flashy. They were stepping on their earnings; they were grinding their earnings to make a point. Period. And it turned into, ‘Oh, you can spin 900 times—great!’ It’s all storytelling at the end of the day.”

Why He Writes Out His Dance Breaks Like a Story

“If I write it on the page and I feel it flows, then I can choreograph to it. Because then I feel, at least in my head, I can give justification to the steps. I can give justification of why things are there if Patti LuPone asks or if Bart asks or if the costume designer asks, ‘Why would you want a fan that big?’ ”

Why He Changes Steps When Actors Don’t Feel Comfortable

“They have to embody this eight times a week. They have to use whatever I’m giving them to push the show forward. As long as they can stay with me on the same page, that we’re all telling the same story, then I genuinely don’t care. The steps are gravy.”

Accolades

“The whole awards thing—I don’t think about that. When I’m doing a show, I just have to figure out these numbers.”