The Dance World Isn't Welcoming to Non-Binary Artists—And It Starts With Audition Notices

During a period when I was intentionally taking a step back from performing, I was especially sensitive to the question, “So, are you auditioning for things?” Besides the insecurity of being a freelancer not hustling in that way, I also rankled at the complexity of what it means for a non-binary performer to audition.

To put it bluntly, there aren’t many safe opportunities for us. That’s because so many audition listings include gender-exclusionary phrases, so trans and non-binary artists either aren’t eligible to show up or aren’t sure whether or not they’d be welcome.

To be fair, sometimes breakdowns are intentional and important. If a work is narrative-driven, the choreographer might be seeking dancers to embody specific genders, races, abilities, etc. In these cases, employers can save a dancer time if they’re not the right fit.

Nguyen modeling in Audio Helkuik’s designs at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Hannah Cohen, courtesy Nguyen.

Even so, an explanation as to why a work is seeking a specific gender could clarify for everyone involved what the work’s priorities are. Plus, irrespective of gender identity, anyone could and should be free to explore and challenge what “masculinity” and “femininity” mean. (Unlike race, which is also a social construct but not a costume that anyone can try on—that’s cultural appropriation.)

Here are some problematic phrases I’ve found in researching audition notices and some easy tweaks to make them more inclusive:

Don’t say: “Male and female,” “men and women” or even “all genders” as a catchall for all dancers

These phrases can feel careless and problematic if they’re meant to include everyone. The first two reinforce the gender binary—the idea that a person should be either male or female. They also contribute to the erasure of non-binary people who are neither male or female. Also, some people don’t have genders.

Instead say: “All or no genders” or even just “dancers” or “performers”

Nice and simple.

Reconsider: “Male” or “female” dancers

Without explanation as to why an artist is seeking one or the other, this phrase can also be exclusionary. Trans men are men and trans women are women, but is this project open to trans folks? And what about non-binary, genderqueer, agender, gender-nonconforming, genderfluid, two-spirit and dancers of other gender identities? Is your work interested in these folks?

How about: “Femme” or “masc” dancers

These terms shift the focus from gender identity to gender expression, including all kinds of queer people who present more feminine or masculine if that’s what you’re interested in.

Don’t: Look for token trans or non-binary dancers

It’s hard to deny that “diversity” and “inclusion” are some trendy buzzwords. Audiences and organizations are increasingly prioritizing the work of historically under-represented artists in programming. But diversity isn’t an aesthetic. Choreographers can hire queer/trans artists but still make cis-heteronormative work. Bringing in queer dancers without considering our real bodies and histories risks perpetuating the same erasure as not having us in the work at all.

Do: Think about the kind of work you make and the dancers you employ

What drives you to create a certain project and hire folks of certain identities for it? Is it to check off boxes for your grant application or broaden the conversation around what dance can do? Audition notices are just one part of this question.

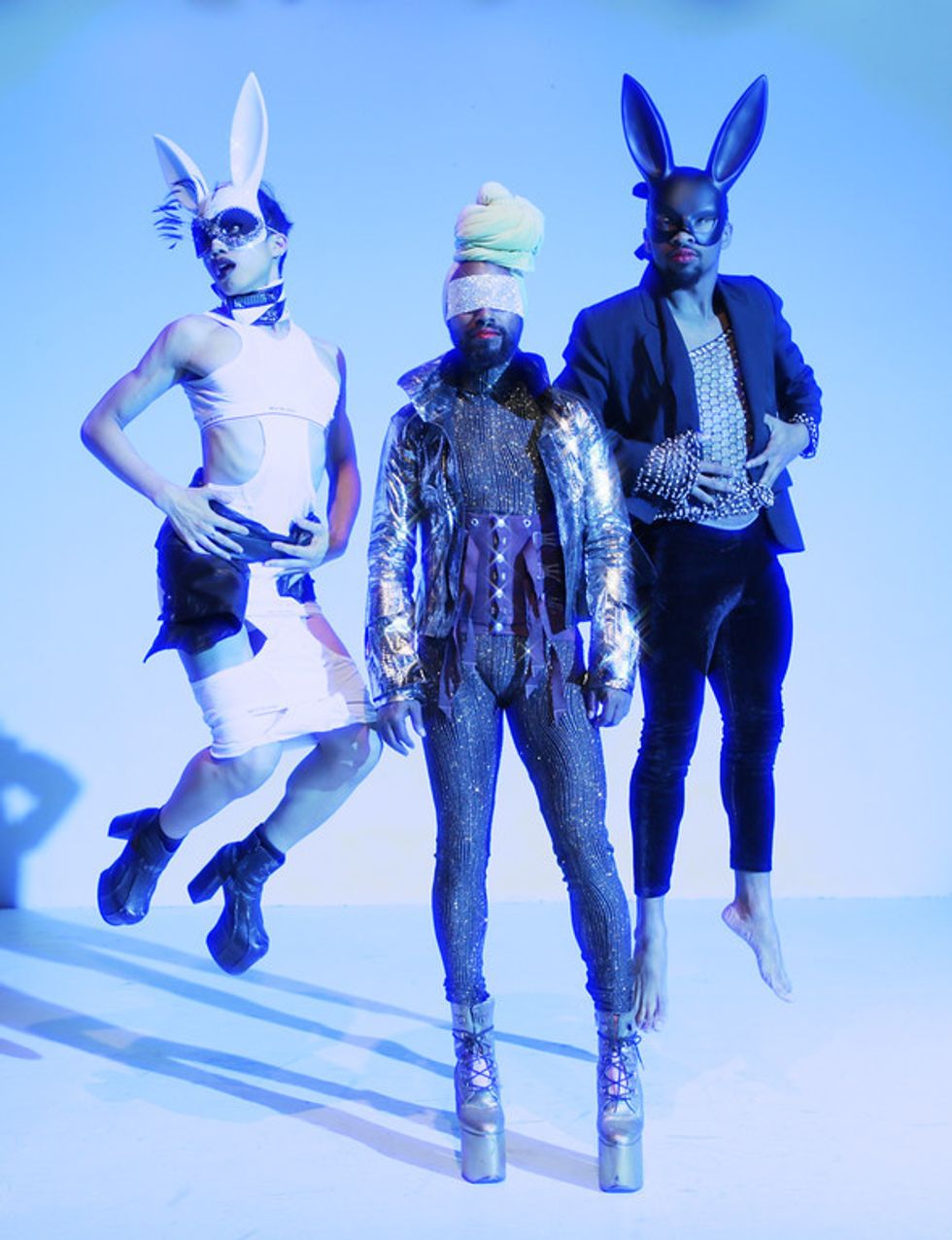

Nguyen (left) in Monstah Black’s Hyperbolic! (the Last Spectacle). Photo by Peter Yesley, courtesy Nguyen

Non-cisgender representation is still alarmingly low in the dance world. This is in part because it’s largely not safe to be trans or non-binary in America. Being a queer artist onstage can be risky but full of possibility. Dance has the potential to create safer spaces by upholding gender-inclusive values and practices—and it can start with who is welcomed into the audition room.