What It Feels Like to Watch Your Own Opening Night

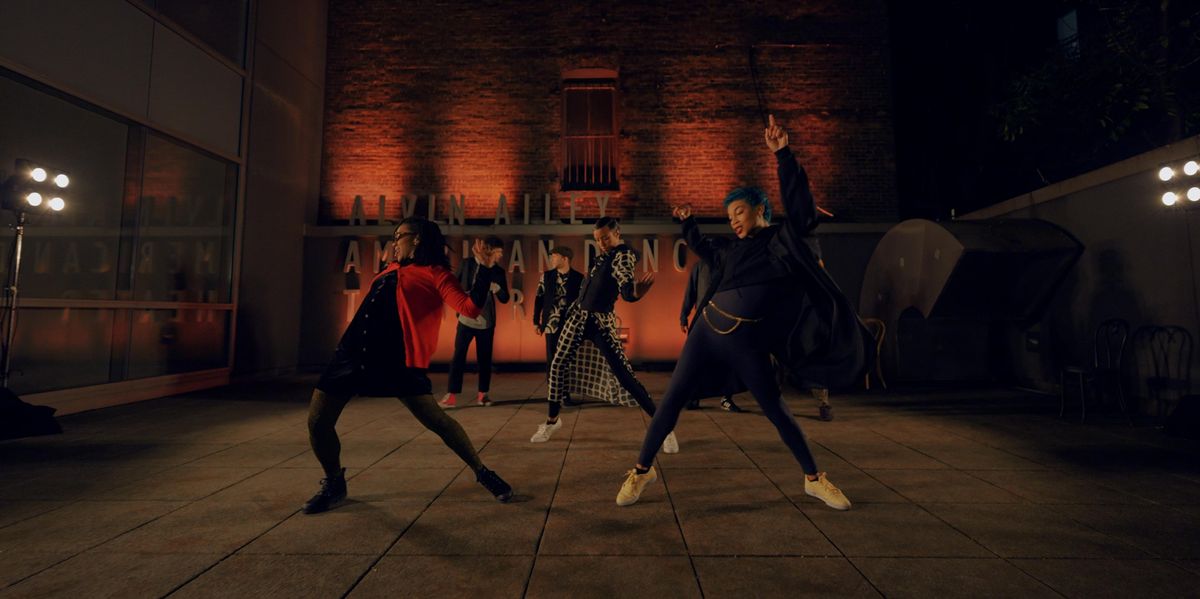

I remember the first time I watched Courtney Celeste Spears perform. It was 2012 and she was a freshman in the Ailey/Fordham BFA program. Her solo in Hope Boykin’s RE…Porter was the type of performance that made you think “Wow. This girl has something special.” I was working at The Ailey School at the time and ended up seeing Spears premiere countless works as she ascended into Ailey II and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. So, when I found myself watching her in a virtual premiere this winter, I instantly wanted to know what it was like for her to be watching her own premiere too.

Over this unusual year, dancers in different styles and at different stages in their career all felt the tremendous pressure that being on camera puts on a dancer. For many, they had their first experiences with the raw vulnerability of being both the talent and the audience simultaneously. Although performances are now slowly transitioning back to the live stages, many remain virtual—and the practice of being on camera remains novel to many dancers.

Spears’ first premiere of a work filmed in person was Jamar Roberts’ A Jam Session for Troubling Times, which she watched on opening night at home with her family. “What they saw for the first time, I saw for the first time,” says Spears. “I hadn’t seen any cuts, any edits, any credits. I knew what my costume looked like, and I knew what the lighting kind of looked like, but everything is so different on camera. I really experienced it with the world.” She felt an odd dissonance of knowing what was going to happen choreographically, but not how that container would be packaged.

Although, like most dancers, she typically struggles with watching herself perform, Spears found she was able to overcome usual hypercriticism because she was simply so grateful for the opportunity. “The moment it started, I just was filled with so much joy to see what we created in a time that was trying to throw everything against us,” she says. “It just felt very, very indescribable.”

What many artists have missed is the community that surrounds an opening night. As a creator, Cameron McKinney, artistic director of Kizuna Dance, seeks feedback from the audience, noting that an online premiere can feel “a little bit more hollow” than in-person. In pre-pandemic times, he would hear reactions over a post-show drink and have a “sense of community from seeing and experiencing something together,” he says. “Online, people just put up an emoji and move on. I really don’t know what stuck out to people or what resonated.”

To that end, Spears tried to make her premiere night as much of a party as she could. She and her family may have been on the couch, but with the stream connected to a big-screen TV, and wine and snacks served, Spears says that “out of respect for the art, I needed to create as much of a space where we all came together to watch it. We need to give our full attention to this the way that we would if we were sitting in a theater.”

Still, the full experience of performing live is impossible to replicate on screen. Isabella Boylston, principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre, says she’s missed the exchange of energy between artist and audience. “One of the biggest challenges I’ve found has been stamina,” she says. “You can run things in the studio as much as you want, but there’s just a different level of fitness and stamina you can seriously only get from performing. The adrenaline really takes your performance to another level, and it’s hard to recapture that without energy from the audience.”

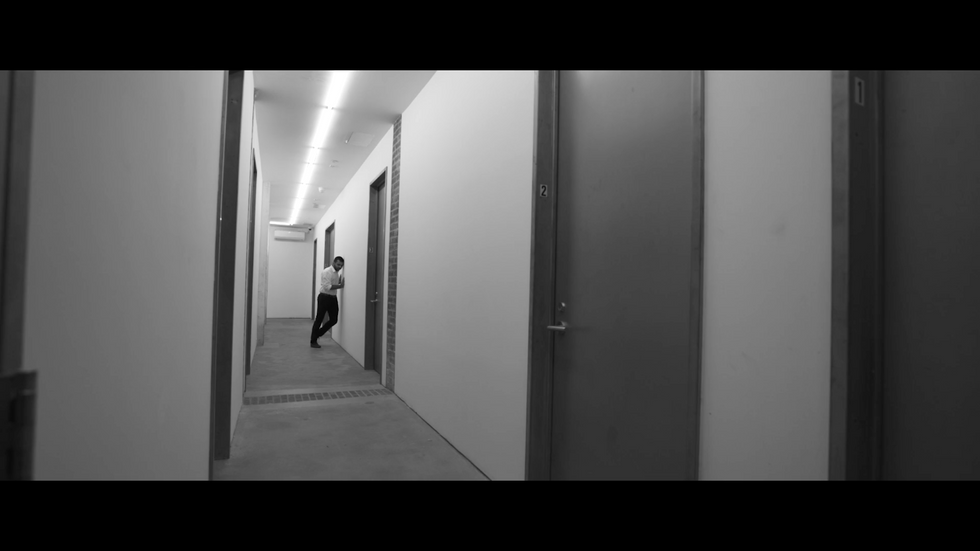

A still from Muted Lows

Courtesy McKinney

There’s also the struggle to get the perfect performance that will remain in perpetuity. McKinney, whose Muted Lows was commissioned by Alfred University, says, “You have the ability to really direct what the audience sees. If you’re onstage and you have an ensemble, the audience can choose to look at one person, or the whole stage, or they can look away. In film, whatever is on screen is what you want them to see.”

For the performers, that ability to zoom in can be nerve-racking. Boylston recently filmed The Seasons for ABT’s virtual spring season, Live from City Center, and despite the title, the performance was not streamed live, but rather she and partner James Whiteside spent three hours filming the five-minute pas de deux. “I thought, ‘Oh, I can easily get this, it won’t take that long…but it always ends up taking so much longer because, as dancers, we’re such perfectionists.”

Spears says there’s a curation that’s different from the spontaneity of performing live. “With the stage, what happens happens,” she says. “If I fall, that’s it…Oops, I’ll try again the next time. But filming was the opposite of letting it all go.”

Boylston, who watched ABT’s spring season at home with her husband and Whiteside (“We just didn’t want to be alone; we needed to get together and watch this”), admits she struggled with her perfectionist mentality as an audience member. “I enjoyed seeing my friends dancing much more than I enjoyed seeing myself dancing for sure,” she says. “I feel like you can sit back and just appreciate what other artists have to offer, whereas when you’re watching yourself, you’re just going to be very self-critical a lot of the time.”

Boylston encourages young dancers who may be seeing themselves on camera this recital season to use it as an opportunity learn. “But at the same time, just know that you don’t see what other people see, and it’s impossible for you to watch yourself objectively,” she says. “Don’t be too hard on yourself, because that’s really counterproductive. You need to love yourself.”

Christopher Duggan, Courtesy Boylston

Spears found herself watching Roberts’ piece over and over again. “I couldn’t stop. I couldn’t stop watching my friends. I was filled with so much joy to see what we created as a group.” She also became highly aware of the larger community that got to enjoy the premiere. She’s used to performing in theaters that can hold 1,000 to 3,000 people, but within minutes of premiering, the piece had received 15,000 views and was getting hundreds of comments. It was a unique silver lining to reach new audiences in a time when the world felt so disconnected.

Each of these dancers proclaims unequivocally that if given the choice between a virtual or in-person performance next, they would choose the in-person performance. Spears explains, “I think every artist—everyone in the world, really—has their house where their talent flourishes. You know, a carpenter performs best in a woodshop…everybody who is good at something, they know where that energy, love and time is cultivated in its most beautiful essence. And so, not that I don’t love film, but I miss the theater, I miss the live aspect of art.”

Looking ahead at when she can be back onstage, Boylston says, “I think it’s going to be really, really emotional for everyone—the audience and the dancers. And I can’t wait.”