Op-Ed: Dance Theatre of Harlem Was My Wakanda

Recently, I went to see Black Panther. When the aircraft penetrated the invisible force-field cloaking the fictional African nation of Wakanda—a country unmolested by European colonization, one that is powerful, prosperous, thriving and the most technologically advanced society in the world—I literally gasped.

Evan Narcisse, a pop culture critic who co-writes “The Rise of the Black Panther” miniseries told The Washington Post, “Wakanda represents this unbroken chain of achievement of black excellence that never got interrupted by colonialism.” It presents African peoples with agency, self-definition and identity. In Wakanda there is no “black” excellence, there is just excellence.

As a watched, I began to I understand the phenomenon that was taking over the black community: We were seeing an image of pan Africanism where we were all welcomed and included. For the first time, we were watching how we feel about ourselves before the world projects its image upon us and tells us differently. In it we see “what might have been.”

Leaving the theater, I was experiencing a sense of awe and pride for my people and repeating, “Wakanda forever.” I realized that this utopian world was triggering real-life memory harkening back to the first time I saw Dance Theatre of Harlem as child in 1978.

I was 8 years old when Arthur Mitchell and his Dance Theatre of Harlem came to Philadelphia with the show Doin’ It, which incorporated 12 local children in every city. My father took me to the audition, and out of 200 children I was selected to be one of the 12.

To me, Mr. Mitchell was like a King T’Challa: regal, charming, dynamic and mystical. His voice boomed, his smile lit up the universe. When he made the pronouncement that since we were to be paid, we were now “professionals,” we all pulled up a bit more, and puffed out chests our as if we had been inducted into the Dora Milaje special forces of Wakanda.

We rehearsed separately from the company until tech rehearsal, when we were ushered into the theater to be integrated with the rest of the production. That, for me, was like entering Wakanda. My eyes were greeted by a cornucopia of sepia-toned ballet dancers, all with tights and pointe shoes that matched their faces and arms. It was revelatory, akin to the feeling I had watching the five tribes of Wakanda gather at Warrior Falls.

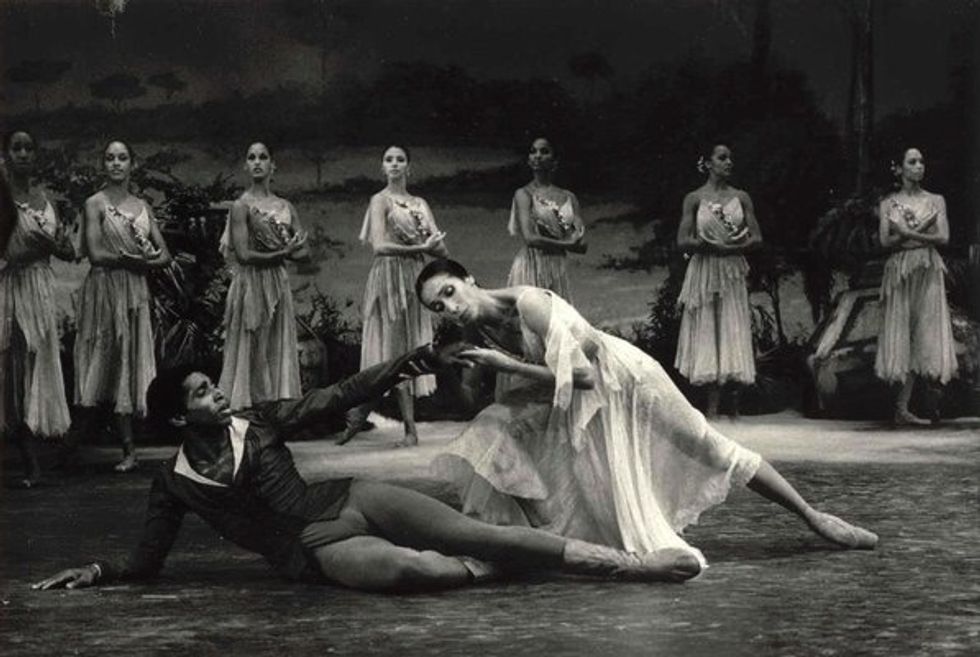

DTH in Creole Giselle (with corps dancers crossing their arms like a balletic Wakanda salute)

As a black ballet dancer, you experience an incredible sense of isolation while training in the oppressively white world of classicism. It does not have to try to be exclusionary or antagonistic because historically, this is its tradition. For young black bodies, entering that space is the antithesis of “entering Wakanda”; it feels as though you are penetrating a force-field of white privilege. The otherness of your skin tone seems to illuminate like the vibranium fibers of the Black Panther suit, and like the suit you must learn absorb all the opposing energy that comes at you (directly or through micro-aggressions) and sublimate it into a shield, much like those worn by the border tribes of Wakanda.

To my 8-year-old self, DTH was like an oasis, something that I could only dream of. When I laid eyes on a world of ballet dancers who looked like me and loved what I loved, it was life-altering.

Though my “ballet” Wakanda is in many ways a direct contradiction to the actual one (since ballet is a European art form), this correlation is less about the “what” it is, and more the “how” it made me feel.

DTH normalized blackness within the European aesthetic of ballet. While adhering to the technical strictures of ballet, it took artistic license with things like the color of tights and shoes, hairstyles, the uniformity of the corps de ballet. The DTH ballerina was allowed to be a woman—she had hips, tits and agency onstage. Our signature walk dubbed “the DTH tip” had a sassy flirtatious switch about it, apropos to the women of our culture. Yes, it was a European form, but we were “Doin’ it” and doing it well. DTH made it ours—culturally.

During the ’80s, the profound pride and awe that DTH inspired could not be denied. The elegance, sophistication and grace of the artists both onstage and off was cultivated by Arthur Mitchell, who understood better than anyone what dancers endured to arrive at that level. He drilled into students and professionals alike the adage, “You represent something larger than yourself.”

It was something that we already knew, but he sublimated that reality from an albatross around our necks to a necklace of diamonds we wore like that of the Black Panther’s—at our command it would transform into an impenetrable suit of protective armor able to absorb the slings and arrows of bigotry, racism and inequality.

Like the Wakandans, we too were sent out into the world to teach and build. Whether dance educators and directors, choreographers, college professors, administrators, lawyers or entrepreneurs we sailed forth carrying with us the standard of excellence and pride that had been embossed on us from our experiences within the walls of 466 West 152nd Street, Harlem, New York. Those of us who had the privilege to inhabit that rarified space remember because it lives within us.

Dance Theatre of Harlem was our Wakanda, forever.