What Does It Take to Challenge Dance's Gender Norms?

For Sean Dorsey, the dance studio used to be a source of pain that had nothing to do with dancing. “I would go to the women’s dressing room and change there,” he says. “That was, every day, this kind of knife in my heart.”

Though the classes thrilled him, having to use facilities that didn’t correspond with his gender identity made him feel extremely self-conscious and ashamed. Later, as an adult, Dorsey noticed that “people like me weren’t onstage. Our stories weren’t being told through dance.”

An increasing number of out transgender performers and choreographers like Dorsey (one of Dance Magazine‘s “25 to Watch” in 2010) are working to fill that gap by challenging gender norms in dance, onstage and off. For an art form with deeply ingrained gender divisions, that’s no easy task. Currently, from the moment a child steps into a dance studio, their training is often determined by gender. Ballet in particular breaks up genders into separate classes, demands gender-specific clothing, teaches gender-specific combinations and values gender-specific qualities. By explicitly addressing the politics of gender in their work and advocating for changes to these traditions, transgender artists today are helping to expand dance’s representation of gender.

A self-described “physically precocious” kid, Jules Skloot began ballet early, while being raised as a girl. But at age 5, he came home and said, “It’s not what my body wants to do,” he recalls. “I had a sense that I wanted to dance, but not in that way.” Even when he started serious Graham training, the leotards and flowing skirts felt wrong on his body as he went through puberty. “I just felt a lot of discomfort in costuming,” he says. Still, he was drawn to the way modern dance involved people of all genders, shapes and races partnering each other and dancing together. “That was exhilarating to me,” he says.

Jules Skloot. Photo by Angela Jimenez, courtesy Skloot.

Shortly after receiving his master’s in dance, Skloot started working with Katy Pyle, a cisgender (non-trans) dancer who trained in classical ballet but was interested in scrambling the gender politics of the form. Pyle points out that, unlike some postmodern and experimental dance that tends to ignore gender, her Brooklyn-based company Ballez wants to tackle it head-on. “We’re using these definitions of masculinity and femininity to create something that’s not neutral, but it’s layered and it’s complicated,” she says.

Ballez’s ensemble represents the spectrum of gender identities and it doesn’t adhere to traditional gender roles in casting. For example, in the company’s 2013 take on The Firebird, Skloot danced the titular role, usually portrayed by a ballerina, and Pyle’s character was billed as the “lesbian princess,” while the “princes” were danced by women, transmasculine and gender-nonconforming individuals. Gender isn’t erased, but it’s intentionally and shrewdly dissected. That ethos offers a place in the ballet canon for those who, like Skloot, felt excluded from it in their youth.

Sorceress and Princes from The Firebird, a Ballez. Photo by Ian Douglas, courtesy American Realness

The experience of valuing the body as an artistic instrument while also feeling disconnected from it can be a disorienting one. Choreographer Arrie Davidson came out as transgender three and a half years ago, though she always knew she was a girl and refers to her childhood as “when I was pretending to be a boy.” As a professional dancer, she spent hours editing her bio to avoid using the pronouns “he” or “she.”

Now in her 40s and undergoing hormone-replacement therapy, Davidson says that the hesitation to physically transition sooner was partially personal, “but part of it was, ‘What does that mean as a dancer?’ ” She wondered, “If I change my body, is my career over?” She found no out transgender dancers to point the way.

“It’s scary to go, ‘Well, what is an audience going to think of me now? What are they going to perceive? How do I costume myself?’ ” Davidson says. Prominent transgender celebrity Caitlyn Jenner may have given people the impression that a transition can take place overnight, but it is a complex multiyear process. Davidson decided she wouldn’t stop performing. “I’m on the roller coaster and I’m not turning it around,” she says. Instead, she grapples with it in her work, like the recent production Wonder/Through the Looking-Glass Houses, a modern take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice tales, in which she uses her character, the White Rabbit, to slyly address transgender issues.

Arrie Davidson with Cecily McCullough in Wonder/Through the Looking-Glass Houses. Photo by Caitlin Shea, Courtesy Davidson

She has also learned to take pleasure in, and laugh at, the process of dealing with a new center of gravity as her body develops curves. Fortunately, she’s been able to use her well-honed physical intuition as a dancer to adjust her workouts to give her changing body what it needs. The shift has been psychological, too—losing a bit of control over her body has led to an “openness of exploration on a deeper level” because she no longer judges herself based on past expectations.

Initially, the San Francisco–based Dorsey decided not to physically alter his body. “I was really out and outspoken as trans and making work for 10 years before I chose to take testosterone,” he says. “There’s a spectrum of the way people express as transgender.” During that time, he dealt with the discomfort of dancing with a binder, a restrictive wrap that flattens the chest. He decided to have top surgery (a chest reconstruction similar to a double mastectomy), which he calls a “massive removal of a daily, hourly stress that I lived with moving through the world.” Several years later, he began to take testosterone.

The gradual transition allowed Dorsey to closely observe how his dancing changed in relation to his body. His shoulders and chest broadened, which, like Davidson, shifted his center of gravity; he noticed greater physical strength, too. As all dancers learn to do, Dorsey was checking in with his body every step of the way. “It felt very aligned and very right, every moment of that progression.”

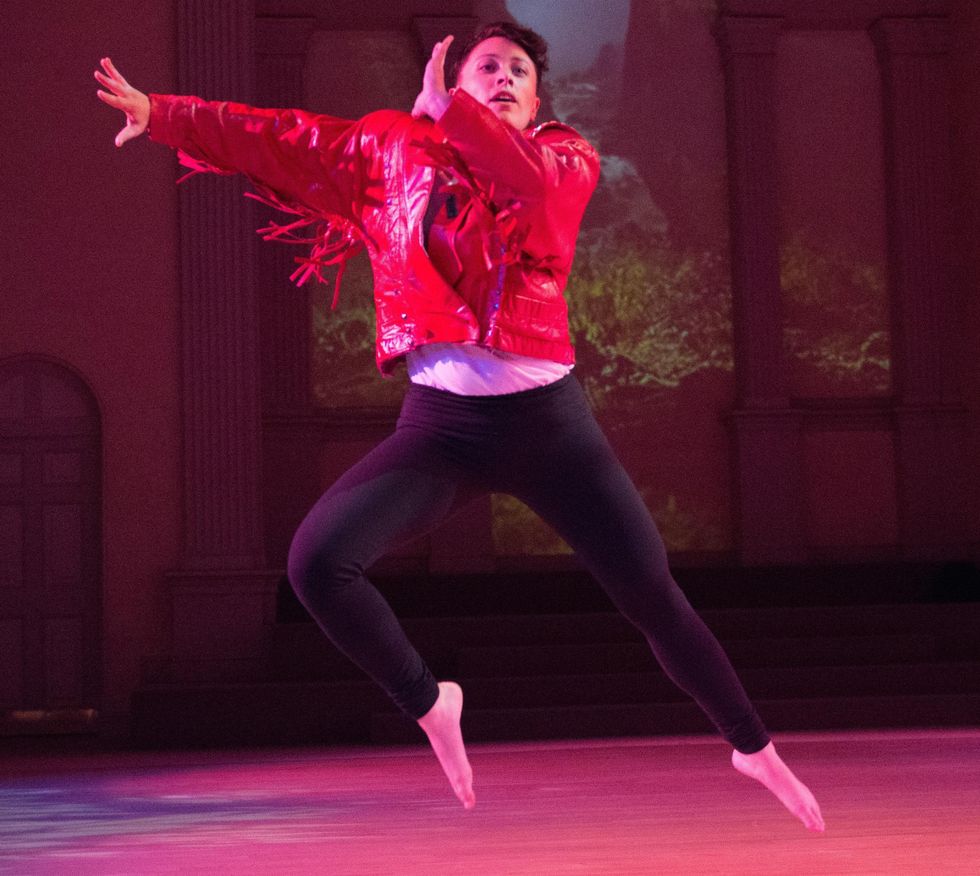

Sean Dorsey. Photo by Lydia Daniller, courtesy Dorsey

That careful attention has served him well in teaching. “I have a unique insider perspective from different parts of the gender spectrum,” he says, which helps him connect with students and dancers of all genders.

Transitioning is a very personal journey, but dance is a communal art form. Transgender performers point out that most studios, schools, performance venues, companies and choreographers can do more to make transgender and gender-nonconforming dancers feel welcome. Dorsey shares that many avoid dance studios, yoga studios and gyms because “all of these spaces continue to be profoundly unsafe for trans people, both physically and emotionally.”

Over the past several years, Dorsey’s company has traveled around the country presenting work like The Missing Generation, The Secret History of Love and Uncovered: The Diary Project, which each address aspects of LGBTQ experiences. He says that “one of the seeds we plant” is asking venues to provide at least one non-gendered restroom.

In terms of training and performance, children who come out at a young age should be welcomed into the class that corresponds to their preferred gender identity, says Davidson. Later in their career, making transgender and gender-nonconforming dancers feel welcome at auditions is another step of inclusion. “Every audition, I put ‘All Genders Welcome,’ ” says Davidson.

Some styles of dance, like ballet, which are more driven by tradition, seem to be less open to transgender dancers compared with contemporary and experimental dance, which tend to be more interested in challenging social norms. Still, Skloot warns choreographers against using transgender dancers just for the sake of incorporating edgy politics, which can feel “tokenizing.” “There are so many other parts of me,” he says. “And so many other things I want to explore artistically.”