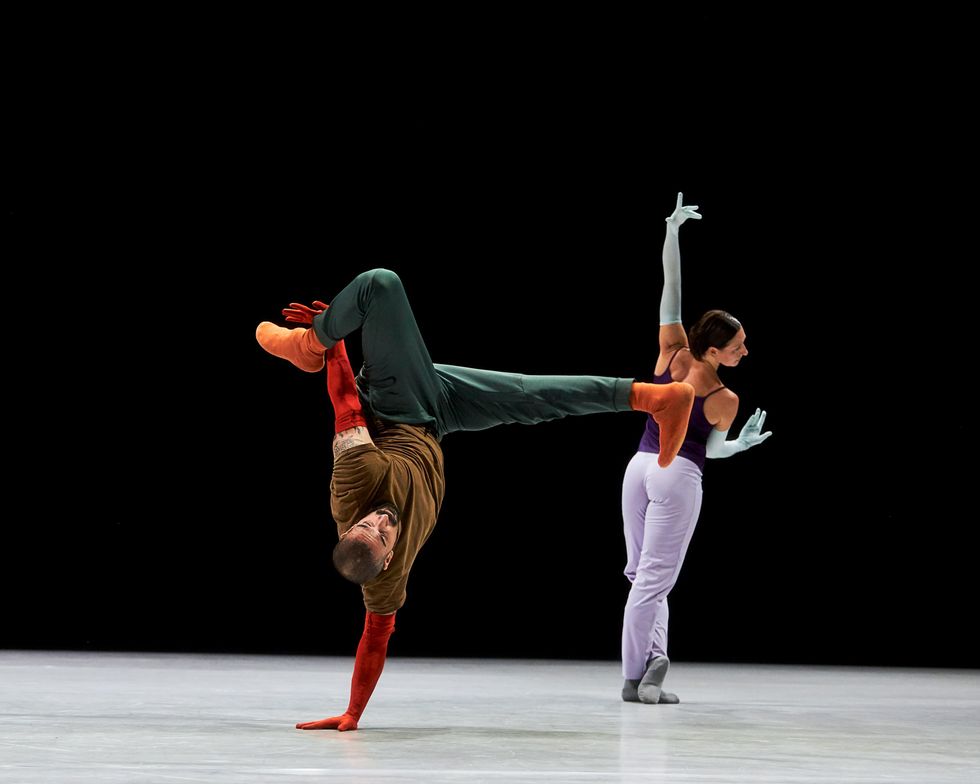

Rauf "RubberLegz" Yasit: The B-Boy Who Throws Genre Distinctions Out the Window

Scroll through the Instagram feed of Rauf “RubberLegz” Yasit, and you’d be forgiven for not being able to define exactly what kind of dancer you’re watching. The way he spins on his head might remind you of classic break-dancing, but then he’ll balance in a headstand like a yogi as his arms and legs twist to create intricate shapes in the air. Some of his movement experiments have a contemporary flair, but in his intense flexibility and contortion-like poses, you may also see glimpses of a circus acrobat.

Defining him, as it turns out, is completely beside the point, and his ability to exist in the space between genres is one of his greatest assets. Since beginning his career as a self-taught b-boy competing in Germany, Yasit has become one of the most sought-out collaborators in the contemporary dance world, working with choreographers like William Forsythe and James Gregg, collaborating with companies like Puma and Burberry, and lending his skills to multidisciplinary projects.

“There have been very few street dancers that have been able to enter the concert scene,” says choreographer Jacob Jonas, a friend and frequent collaborator. “Rauf has definitely bridged that gap.” Through years of meticulously honing his craft and staying curious, he’s carved out his own unique place in the dance world.

Mohamed Sadek, Courtesy The Shed

Yasit grew up in Celle, a small city in Western Germany. By age 3 or 4, he had already started learning from his father, who taught traditional Kurdish folk dances. “It’s part of our culture—we dance a lot at weddings and family gatherings,” Yasit says.

Another dimension of the dance world opened to him when he saw the 1997 music video for “It’s Like That,” a Jason Nevins remix of the Run-D.M.C. song. The video depicts a dance battle, and Yasit was especially captivated by a b-boy named Jacob “Kujo” Lyons, whose wild, lightning-fast solo feels at once frenetic and hyper-controlled. Yasit wasn’t sure exactly what he’d seen, but he knew he had to be a part of it.

He learned about a local school where a group of dancers met twice a week, bringing their own cassette player and reserving a room to practice. Yasit began attending religiously, plus training on his own at home. He started making connections with as many dancers as possible, and entering competitions.

“In breaking it’s very normal that you create your own identity,” he says. Having a signature style or moves that you’re best at helps you stand out in competitions. But Yasit often found himself drawing inspiration from things outside of traditional breaking. After he hurt his back doing flares, a classic power move, he learned some yoga stretches and got the idea to go into a lotus pose while in a handstand. He loved Cirque du Soleil, and looked at the way those artists balanced on their hands.

“As b-boys we get on our hands too, but I said, ‘I want to balance like a circus artist, because there’s so much I could do,’ ” he remembers. “People would say, ‘This has nothing to do with dance,’ because I was not a traditional b-boy.” That didn’t stop him. Instead, he embraced the name RubberLegz, given to him by a mentor named Maxim from his first dance crew.

Yasit’s first theatrical opportunity came in 2007, when Zekai Fenerci, co-founder of the German company Renegade Theatre, met him at a competition and hired him to be a part of a production, Cage. The show blended hip-hop, contemporary and circus movement. “I fell in love with theater. I was like, ‘Wow, I can play more, I can take my time more,’ ” Yasit says. “I had to dance a long solo where I had to build up. I was able to dive more into my style and see what I was able to do every night—some of this difficult stuff that I was doing in competition, I can do one or two times and then I’ll be exhausted.”

He loved the freedom he found in contemporary dance, and found a mentor in former Pina Bausch dancer Malou Airaudo, who worked on the show. “I remember she was giving me some corrections or ideas, and I could feel how different it was, and I said, ‘This is where I belong,’ ” Yasit says.

After Cage ended, Yasit spent the next five years focusing on his training. His practice was mostly solitary: He often recorded videos of himself and took photos of poses or shapes that he was working on. He would study the images and continue making adjustments until he felt satisfied.

He also earned his degree in 3-D visualization and animation, which added new facets to his dancing. “I could go back and truly work on all my shapes, and think about negative space, how to make something look more complicated, how to create optical illusions in the body,” he says. “Through design I was able to deconstruct and reconstruct what I was doing. I was always saying, ‘How can I make 30 more poses out of the exact same pose, as you are able to do in a 3-D model?’ ”

The next time he took the stage was in 2012, with the German company Flying Steps, for a production of Red Bull Flying Illusion. But after a couple years of touring, he started feeling the urge to explore new ideas. “I saw dancers in the States producing their own films,” Yasit says. “I was like, ‘I need to do that.’ ”

In 2015, Yasit had barely arrived in Los Angeles when he received a phone call asking if he’d be interested in a collaboration with a well-known choreographer. That choreographer turned out to be William Forsythe, and the project turned out to be a short film for the Paris Opéra Ballet’s 3e Scène (“Third Stage”), the company’s online platform for digital creations.

“I had been working on making these really complicated physical knots with pairs of people,” Forsythe says. At the time, he was inspired by the movement in Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and during a Google image search, his team came across a photo of Yasit that popped up under related images.

The resulting film, Alignigung, features Yasit and dancer Riley Watts woven together in a tangle of limbs. Over the course of about 15 minutes, they continuously transform, flowing slowly and deliberately through a series of shapes as the camera circles them from different perspectives.

For Yasit, the experience was slower and more toned down than an adrenaline-filled competition or theater performance. Working with Forsythe taught him to be intentional about each decision, to stretch each movement and let it carry him, instead of constantly shifting from one pose to the next.

That first collaboration led to others, including performing in Forsythe’s A Quiet Evening of Dance at Sadler’s Wells in London and The Shed in New York City. “I did not realize how quickly he absorbed physical information—his capacity to learn, and his desire to learn,” Forsythe says. “He learned some very important ballet fundamentals in five weeks, and he totally got it.”

Yasit had rarely danced primarily on his legs before (he was more often on the floor, on his hands or head). Still, in his conversations with Forsythe, the two found overlap in their search for solving problems through movement. “He’s interested in ideas,” says Forsythe. “When Rauf dances, that’s what his thinking looks like. His work is a picture of his mind.”

Since moving to L.A., Yasit’s list of collaborators has only grown, as more people become captivated by his singular style and his ability to work in a variety of contexts. Jonas first connected with him after coming across his photos on Instagram, and has since brought on Yasit as a choreographer and associate producer for his Films.Dance series. “When I think about Rauf, I think about looking at life through a kaleidoscope—there’s a lot of shapes and transition and abstraction,” Jonas says. “Being able to intersect vocabularies requires a deep sense of inquisitiveness. He’s really had to show a sense of vulnerability.”

For Yasit, breaking is still at the root of everything he does. “I compose like a b-boy. This is my main mindset,” he says. He has even come full-circle and worked with his childhood idol, Kujo, whom he now calls a friend. But some of his most rewarding moments come when younger dancers find him on social media and reach out for advice, or tell him he’s inspired them to dance, just as Kujo did for him back in the ’90s.

“Somewhere on the other end of the world, someone is watching your videos and is training, and they want to now become a dancer,” he says. “This is superhuman for me to think about.”