These Three Tap Legends Argue That Tap Deserves More Respect

In 1989, Congress passed a resolution naming May 25—the birthday of tap legend Bill “Bojangles” Robinson—as National Tap Dance Day, and it has been celebrated annually on that date ever since. For years, the May issue of Dance Magazine featured a tap dancer on its cover to coincide with the holiday and highlight the form.

But some considered the gesture to be mere tokenism. “It feels like a handout,” says tap dancer Jason Samuels Smith. “Our art form deserves more than that.”

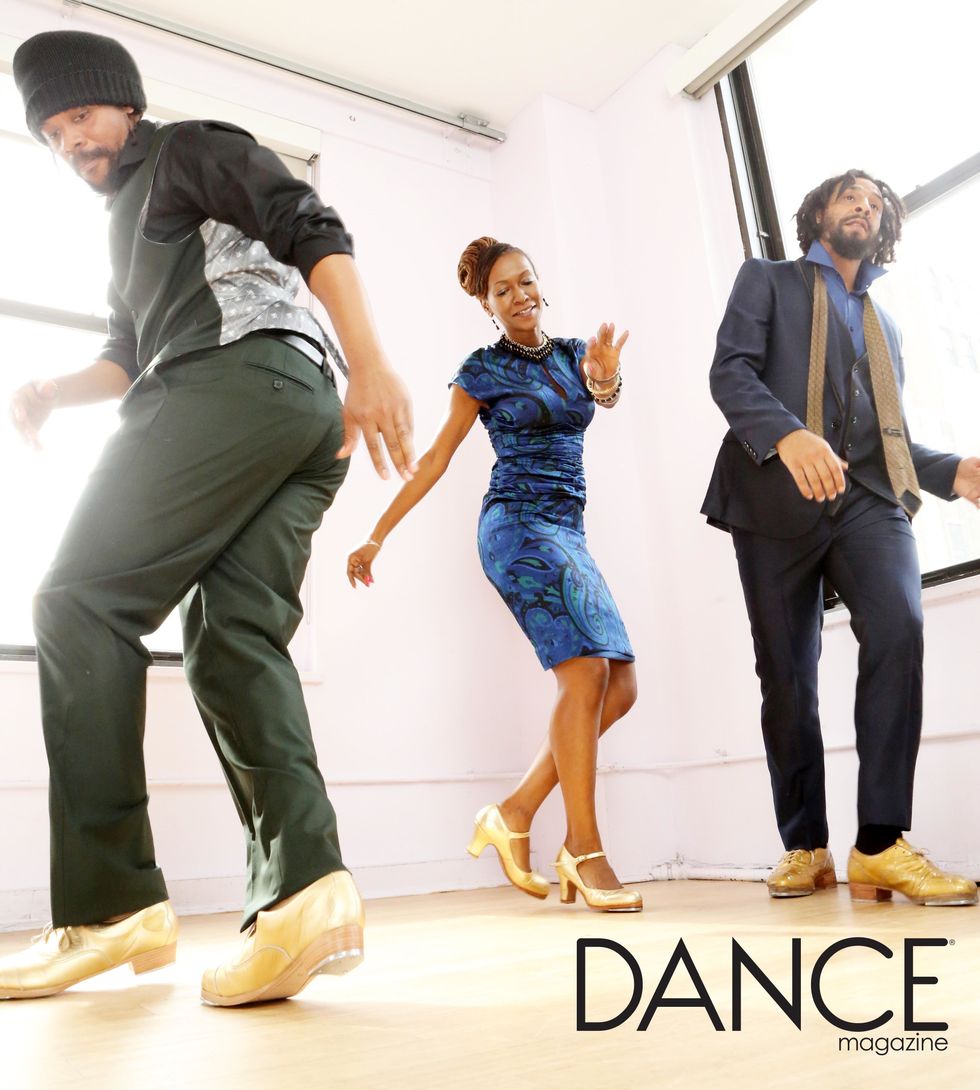

Derick K. Grant, Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards and Jason Samuels Smith. Photo by Jayme Thornton.

The magazine no longer designates a tap issue, but frustrations persist about how, and how much, tap is represented in the broader dance world.

When Smith, 37, and his fellow tap dignitaries Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, 42, and Derick K. Grant, 45, gathered recently for an intimate conversation at Dance Magazine‘s New York offices, they offered frank assessments of the current state of tap and its relationship to other dance forms. They also laughed about the early years of their decades-long friendship, discussed with pride their recent collaborations and championed a new generation of dancers who give them hope for tap’s future.

They Are All Passionate Ambassadors For Tap

In the 20-plus years since they’ve known each other, Smith, Sumbry-Edwards and Grant, who interact with the ease of siblings, have emerged as some of their generation’s most passionate tap ambassadors and among the most exciting performers in dance.

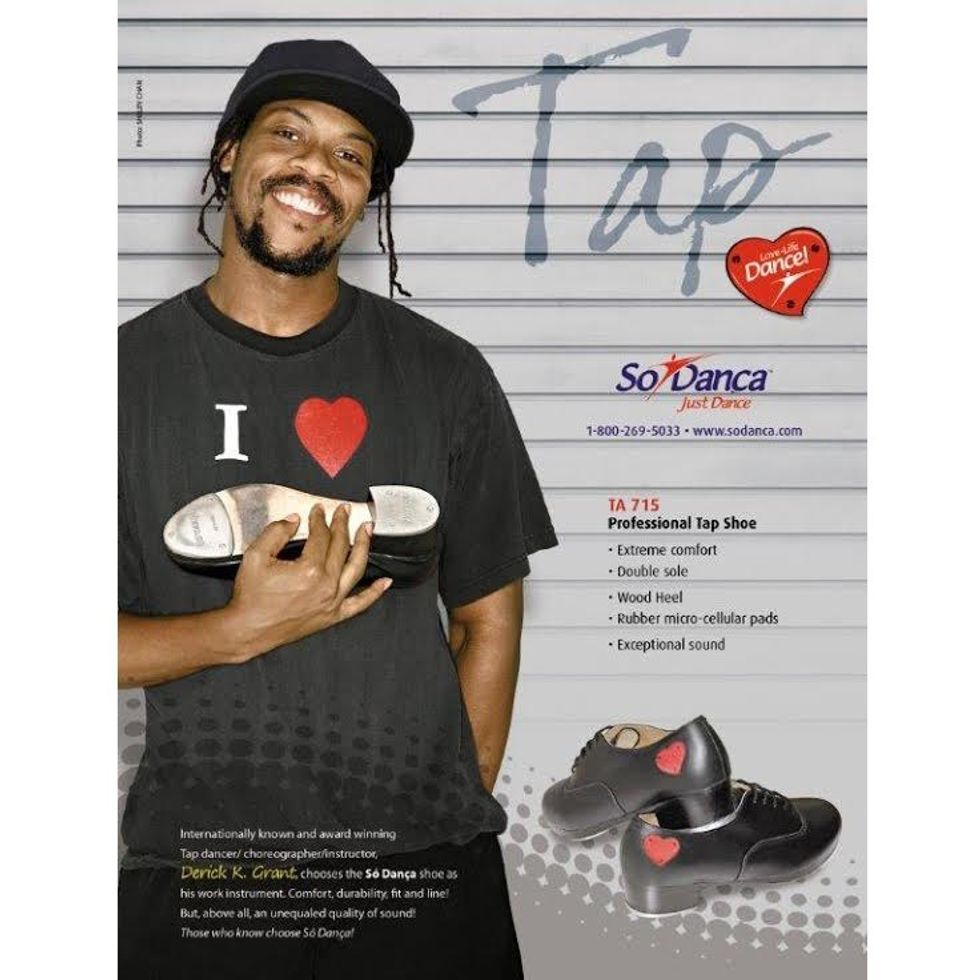

Sumbry-Edwards is known for her elegance and precision, Grant exhibits uncanny power and lightness, and Smith is lauded for his suaveness and attack. (Shoe brands have taken note of their reputation and influence: Sumbry-Edwards represents Capezio, Grant is an ambassador for Só Dança, and Smith has designed a tap shoe for Bloch. “I couldn’t even afford tap shoes when I was growing up,” Smith says in disbelief.)

Grant is an ambassador for Só Dança, while Sumbry-Edwards represents Capezio and Smith has designed a tap shoe for Bloch.

This May, the three co-directed the first annual Tap Family Reunion in New York, a three-day celebration of National Tap Dance Day. Events spanned the city, honoring New York’s contribution to tap and the city’s tap landmarks, like the Apollo Theater, the Minskoff Theatre (where the acclaimed blues, jazz and tap revue Black and Blue ran on Broadway from 1989 to 1991) and the Tree of Hope in Harlem, now a sculpture representing an elm that Robinson used to rub for good luck. “We’re trying to elevate the general tap community’s consciousness,” Smith says.

That focus on history is meant to reconnect the tap festival to its origins: Robinson’s birthday, the role tap plays in American and African-American history and its connection to jazz music. “When you make this culture-less and people-less,” Smith says, “you start changing the dialogue of what tap is.” In August, Smith will also co-direct the L.A. Tap Fest with Cathie Nicholas, the granddaughter of tap legend Fayard Nicholas.

One factor contributing to what they see as a weakening of the link between tap and its roots is happening overseas, where despite growing popularity, the history of tap is not always taught alongside the movement.

Another factor is the enthusiasm for tap that is combined with other styles, like modern dance or hip hop. (All groaned when the word “contaporary” was mentioned.) They say they feel institutional pressure to “dress like other forms in order to sneak into these rooms and be accepted, in order to sneak into this money and get funded,” as Grant explains it. “Tap as it is, for what it is, doesn’t seem to be enough.”

“When you make this culture-less and people-less,” Smith says, “you start changing the dialogue of what tap is.” Photo by Jayme Thornton

The three have largely managed to resist that trend by focusing on producing their own programming of the types of shows that they find meaningful. “We just have to stay true to who we are,” Sumbry-Edwards says. “We know our lineage, we know our history. We want it to be that way, so we walk like that.”

They’ve Been Dancing Together Since They Were Kids

They’ve been walking like that for a long time. Sumbry-Edwards and Grant met in 1984: She was 8 and he was 11 and they were on their way to Rome for a show called the Tip Tap Festival. Both were budding tap phenoms brought to Italy by their teachers, the tap legends Dianne Walker and the brother-sister team of Paul and Arlene Kennedy.

“They’re family,” says Sumbry-Edwards of their teachers, “so that made us family immediately.” (Walker studied with Paul and Arlene’s mother, Mildred Kennedy Bradic, so Sumbry-Edwards and Grant share lineage on the tap family tree.)

And Still You Must Swing at Jacob’s Pillow. Photo by Christopher Duggan, courtesy Divine Rhythm Productions

As a kid Smith was a student of Grant’s, and he recalls watching a 13-year-old Sumbry-Edwards in Black and Blue with a young Savion Glover. Since then, these three have frequently performed together and share resumé highlights: All are alumni of the game-changing, Tony Award–winning Broadway musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk; all have worked with the pioneering Jazz Tap Ensemble. And they continue to collaborate on a number of projects and productions.

In 2006, Smith and Sumbry-Edwards were featured in Grant’s well-received revue Imagine Tap! Two years later, Sumbry-Edwards starred in Smith’s ode to Charlie Parker, called Charlie’s Angels. And in 2016, the three garnered praise for And Still You Must Swing, which Sumbry-Edwards conceptualized and directed. When she was commissioned by the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival to create the show, she knew who to call.

“It was a no-brainer,” she says, pointing to Smith and Grant, sitting on either side of her. Smith pipes up: “It was one of the funnest shows I’ve ever done.”

When Sumbry-Edwards was commissioned by Jacob’s Pillow, she knew who to call. Photo by Jayme Thornton.

Sumbry-Edwards says her intention with that production was to address “the state of the dance,” to connect it back to its history, specifically to jazz and swing music.

They Value Experimentation, But Also Integrity

Offstage, the artists imbue these values in the classes and workshops they teach across the United States and around the globe. “It starts with talking about our teachers, and our teachers’ teachers,” Smith says. “That lineage leads us all the way back to the roots of this dance.”

In this way, they maintain the authenticity of the form from one generation to the next. Though they admit to being strict guardians of the origins of steps, they also appreciate thoughtful innovation.

“Inside of tap you’re seeing people do different things with the foot, with the shoe, things musically, inverted steps, twisted steps,” says Grant. They agree that experimentation has a place in tap as long as the experimenter honors the precedent set by others. “Through the connection, you’ll maintain integrity,” Grant says.

Despite some of their concerns about tap’s direction, the three are heartened by the talent they see coming up. “There’s some young bucks on the rise,” Smith says, and the three mention young hoofers like Jumaane Taylor, Josette and Joseph Wiggan, and Star Dixon, among others.

“Some of these young tap dancers I see, they have the potential to be leaders beyond tap dance in the world in general,” Smith adds. “I think tap is one of the ways these positive messages of enlightenment are going to be carried on.”

Looking at the generation of dancers that they helped cultivate, Sumbry-Edwards, Smith and Grant reflected on their own roles as some of the form’s future elders, though to apply the term to such a young, active trio feels laughably premature.

Still, they’ve watched tap change—and have helped shape it—for decades, so maybe the term applies. “We’ve been here for 30 years, so if you consider experience a badge, then we are vets,” says Smith. “We are elders.”