When Your Choreography Is Literally Fire: Billy Bell Combines His Dance Career With Design

Like most children, Billy Bell tried a bit of everything. Sports, martial arts, academics, dance classes and video games all mixed together into one happy, busy, West Palm Beach upbringing. But when it came to picking which interest to follow into adulthood, he felt he had to choose between two worlds.

Through the door on the left, he could follow his passion for math and science, attending a university for civil engineering and leaping into a structured life of equations and innovation.

Through the door on the right, he could appease his persistent dance teacher by confirming his acceptance to Juilliard and trying to make a hobby into a career he didn’t yet understand.

Everything was pulling him left, but with enough convincing, he eventually swerved right.

What followed was an undeniably successful career as a performer. His bespectacled baby face may be most recognizable from his stint on two seasons of “So You Think You Can Dance,” but he also danced in Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, the hit immersive show Sleep No More, José Navas/Compagnie Flak in Montreal and a Britney Spears music video, all while choreographing his own work and teaching across the country.

But even as his dancing took off, he couldn’t stop wondering: Why did it have to be only one door or the other, anyway?

Amy Gardner, Courtesy Bell

Most of us have been taught that our brains have two separate sides: The left performs tasks based on logic, while the right is responsible for all things creative. Generally, we think one of our halves is stronger, more dominant. Artistry and science are naturally competing paths—choosing one must surely mean abandoning the other.

But Bell, now 30 and living in Los Angeles, has learned to see it differently.

In 2014, he was set to join the cast of Sleep No More and attended the show every night to study the role he’d soon take over. “I would watch the track I was supposed to be learning, but then every other show, I would just sit there, I would just wait and watch the environments pass me by and watch the audience interact with space,” he says. “And it was fascinating.”

How the room’s structure and form affected the experience of both the performers and the audience became as interesting to him as the dances themselves. He saw how the movement was inspired by tangibly interacting with the set; dancers and crowds pushed past each other to get through doors or run up stairways. The loud, energetic scenes occurring in one area were as captivating as the silence and stillness that hung in a room nearby. “It fully changed the way I had perceived performance,” he says. “There are huge swathes of time when you don’t even see a performer. And there are still ways to really understand beautiful narrative. That intrigued me immensely.”

This awakening allowed his analytical interests to reignite inside a space of art, and he decided to keep fanning the flame. He had recently gone back to school at the Fashion Institute of Technology to get a degree in advertising and marketing communications, with a focus on visual presentation and exhibition design, and decided to keep expanding on that. When he left Sleep No More in 2016, he moved to Georgia to get his BFA in interior design, focusing on themed entertainment design from Savannah College of Art and Design.

Today, Bell’s multidisciplinary artistic firm, Cinereal Productions, started in 2014, produces its own work and also curates immersive experiences, consulting and collaborating with other production, design and marketing firms. The company conceived and produced The Unbrunch—an immersive, theatrical dining experience that led guests through the five floors of New York’s Norwood Club—and before last year’s shutdown, they were developing The Acey Deucey Club, a Cold War–era, submarine-themed immersive pop-up bar that hopes to dock in multiple cities next year.

Recently Bell’s career has continued down an even more unconventional path. Since 2019, he has worked as a project designer and choreographer for the environmental architecture firm WET (Water Entertainment Technologies), the company behind the famous Bellagio fountains. He programs the movement of water and fire in large-scale spectacles by writing code and blending technology with architecture to compose the overall experience an exhibition delivers. Recent international projects include the 2020 and 2021 New Year’s Eve celebrations on The Dubai Fountain at the Burj Khalifa, and the show Aquanura, at the Efteling Theme Park in the Netherlands.

It’s a long way from a dance studio, but he’s learned that the principles of creating movement remain the same. “When you’re choreographing on a fountain, the equipment itself is your dancer. However, that dancer, that equipment, is fixed in space. It’s not going to move. It’s hundreds and hundreds of pounds and bolted to cement underneath eight feet of water. So we work with what’s called ‘expressions’—a simple stream of water, a fan of water,” he says.

“As a choreographer, I’ve really learned that an audience is quite patient, actually. We think about developing material so the audience doesn’t get bored, when in reality, if you watch a show at the Bellagio, there’s quite a few phrases that are pure duplicates, that you just watch over and over because it’s satisfying enough of a pattern that you really settle into it.”

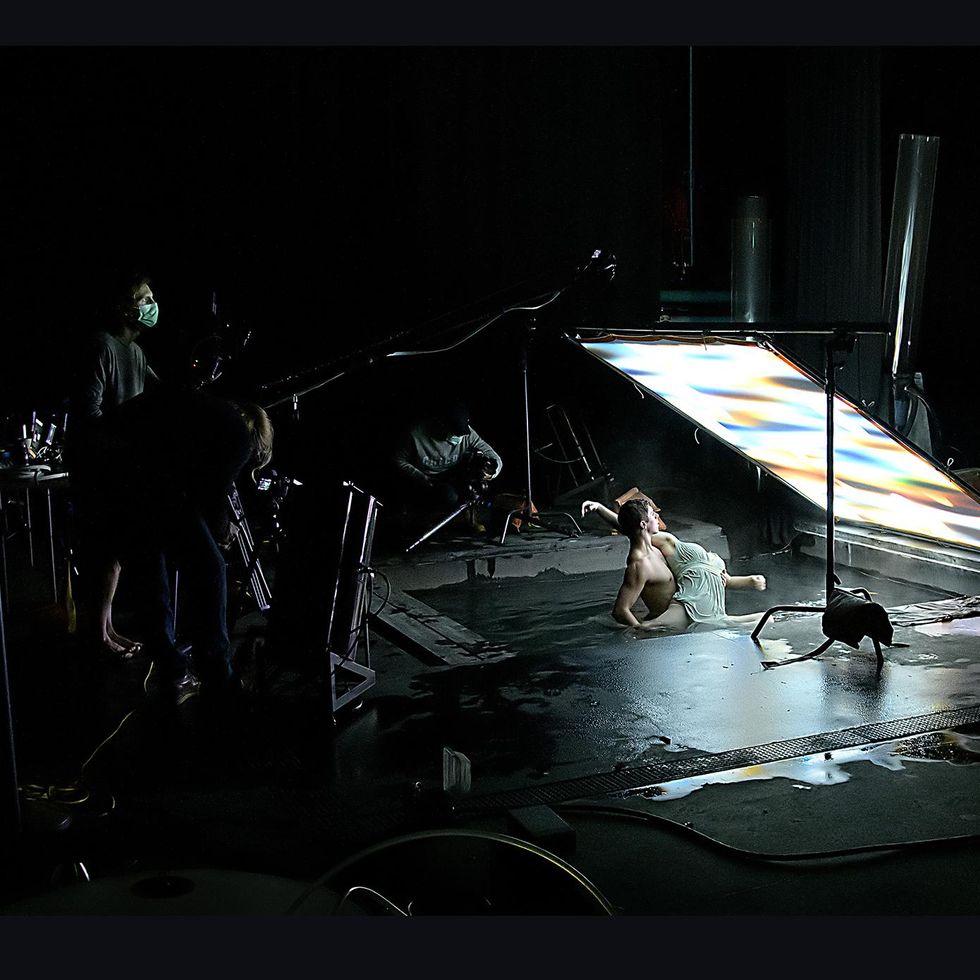

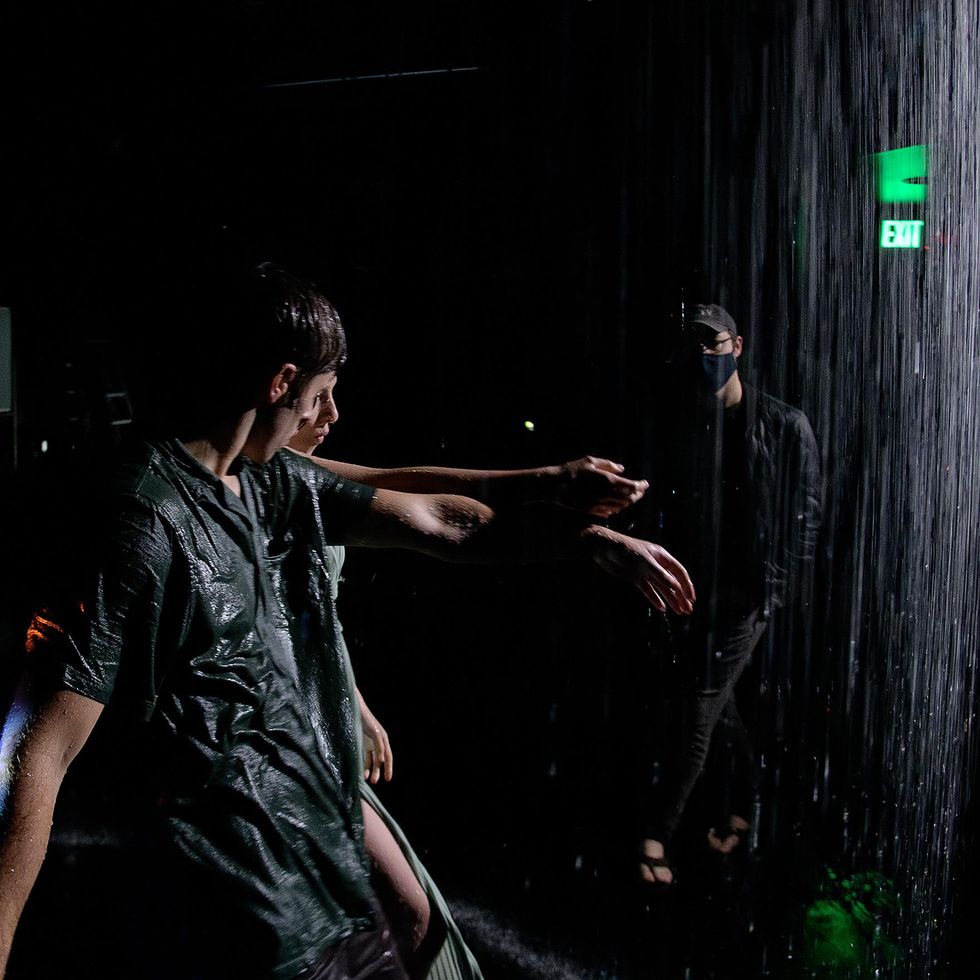

This abstract work pushes him to be a better creator overall, he says. Grand, ethereal designs fit neatly into calculated structure. Most recently, he applied this by blending water, projections and dance in a series of music videos with Lachlan Turczan and Travis Chao for Grammy-nominated artist Phoebe Bridgers.

Ali Castro, one of Bell’s oldest friends and the operations director of Cinereal, told me she’s never been fazed by his atypical direction. “He always, in a really positive way, does what he wants,” she says. “If he’s interested, he’ll bite. He can always find the value in what’s presented to him, whether it’s a completely realized version or an idea about a shoebox. Everything’s valid.”

Bell looks on while filming a music video for Phoebe Bridgers

Jim Doyle, Courtesy Bell

On an individual level, Bell has created a life for himself that erases the left door/right door dichotomy altogether and leaves one big open space where ideas are free to mingle. On a larger scale, everything he’s built is a means of proving that dancers are more expansive than most people think. When asked if his unique career path was possibly a conscious or unconscious slap in the face to the all-too-common stereotype of dancers being one-dimensional, his answer is quickly “Yes, very consciously.”

“I think dance training creates the perfect employee for any field,” he says. “We’re incredibly obedient. We have the ability to lead a group, but also be flexible and trust the group, fall back into it. We’re idea generators, we’re very creative. Brainstorming tends to be very easy with dancers involved.…We’re great at presenting work, we’re great at selling work. That’s what we’re doing already, just in a very specific way that’s tailored to selling a choreographer’s idea to an audience. We are the perfect workforce, in my opinion.”

Cinereal serves as a home where his movement background, design education and business savvy can all come into play. After years of dancing in environments he felt were inequitable towards performers, Bell also structured the company to give them greater power.

“Businesspeople should not be creating art,” he says. “Artists should be creating art, and then understanding the business of art. I want to empower dancers to understand that what they do is valuable, incredibly valuable, not just on an emotional and societal level, but on a monetary level.”

His versatile toolbox allows him to see that artistic solutions can help solve business challenges. “If you orient a show a little bit differently, you can have more people in that space, or you can have more of a turnover, or it can be reset quicker. Really clear design choices can affect the business of art.”

Kamille Upshaw, who attended Juilliard with Bell and later toured with him in Hugh Jackman’s international arena show The Man. The Music. The Show., says she could always tell he was itching for more. “His brain moves a mile a minute. Yes, he’s focused on what he’s doing in the moment, but you can see from the outside he’s also thinking about a million other things.”

This idea of never getting too comfortable, and the pull to deconstruct, rework and change courses has always felt natural to Bell. It reminds him of his father’s work as a general contractor, and he laughs remembering his family’s constantly evolving home. “We renovated the kitchen. When we finished the kitchen, we did the living room. When we finished the living room, we went to the master bedroom. But then by the time you got to your final room, it had been so long that you needed to go back to the kitchen again. It was always a fully functioning house, but it was never finished. I think that sticks with me subconsciously.”