This L.A. Exhibit Honors Blondell Cummings Through Rare Videos and Interviews

Rarely has a woman dance artist (other than Martha Graham or Anna Pavlova) been given an entire exhibit all to herself. But Art + Practice, in South Los Angeles, has teamed up with the Getty Research Institute to highlight Blondell Cummings’ unique place in the dance firmament. Cummings didn’t have big-name recognition like Judith Jamison, Carmen de Lavallade or Suzanne Farrell, but she was an essential bridge to the current dances of cultural identity. The exhibit, “Blondell Cummings: Dance as Moving Pictures,” includes 17 video excerpts of rarely seen works, as well as interviews. It is now at Art + Practice until February 19.

For those who think that “Black dance” and postmodern dance have no intersection, Cummings (1944–2015) is a revelatory figure. She danced with Meredith Monk for 10 years and worked briefly with Yvonne Rainer and David Gordon. Monk’s visionary work, with its dreamlike imagery, haunting vocal flights and repetitive use of gesture, was a strong influence on Cummings. Like Monk, Cummings plumbed her memory, delving deep into her imagination to tell stories through dance. She brought her Black self—body and spirit—into every performance. Her authenticity and fierceness inspired many dance artists, including Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Edisa Weeks and Marjani Forté-Saunders.

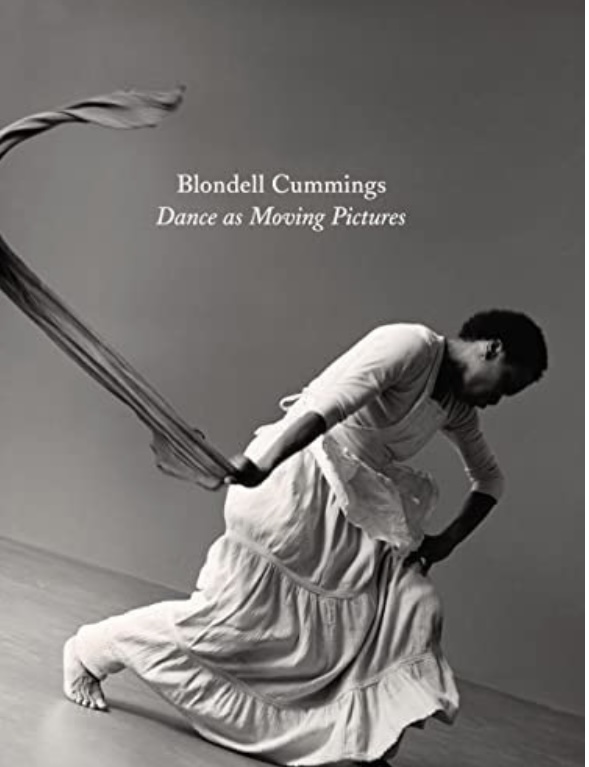

Because of her interest in photography, Cummings developed a stop-action way of moving that became her signature, and she called it “moving pictures.” It was startling to see her actually do this onstage, to click through intense poses with a fevered precision that seemed about to burst into chaos.

Cummings grew up in Harlem and always had a sense of community. The Harlem community. The dance community. The community of women. The community of Black dancers. As I quoted her in “Remembering Blondell Cummings,” she focused on what she called “the poetics of the human condition.” In every work, her hands, her face, her whole body animated the details of daily living, of joy and sorrow, of laughter and pain.

Her 1981 work Chicken Soup was deemed an American masterpiece by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2006. This new status enabled Urban Bush Women to get funding to learn and perform this dance of kitchen memories expanded to keenly felt artistry. Cummings thrusting a frying pan in manic rhythm was unforgettable. Zollar has said, “I wanted another generation of dancers to see the power of the work and know the history of innovation in our field, particularly Black female innovation.” Indeed, one of the UBW dancers who learned Chicken Soup, Marjani Forté-Saunders, was so affected by it that she wedged a brief ode to it into her Bessie Award–winning work, Memoirs of a…Unicorn (2017).

Cummings’ projects were many and varied. She collaborated with Jessica Hagedorn for a harrowing theater piece about war; with Tom Thayer for a tender piece about fatherhood; with Junko Kikuchi in Women in the Dunes; and with body percussionist Keith Terry in intimate duets. She loved traveling and learning, spending much time in Asia, and her travels fed her work. One time, when she was making a dance with rice as the central theme, she commented to me that all cultures have some kind of rice in their diet. She always looked for commonality.

The catalog for “Blondell Cummings: Dance as Moving Pictures,” with gorgeous photos by Lois Greenfield, Beatriz Schiller, Kei Orihara and Cherry Kim, actually completes the exhibit, which is mostly a video installation. We see Cummings in various modes, from glamorous to rough-hewn. The corners of the pages are like a flip-book, so you can thumb through to watch her sequences for hands and legs on the right. It’s her “moving pictures” in book form.

Scholar Thomas F. DeFrantz’s leading essay suggests that Cummings bridged not only the divide between postmodern dance and the more narrative tradition of “Black dance,” but also the divide between Black experimental work and more mainstream Black dance companies. He lovingly describes her bold choreographic investigations over the years. Among his many insights, I felt this one was particularly apt: “She demonstrated how autobiography could be an act of community.”

In another essay, written in 1995 for the publication High Performance, Black dance scholar Veta Goler wrote that Cummings “does not treat the Black experience as isolated from other cultural experiences.” Similarly, in a piece titled “Memories of Blondell,” Meredith Monk writes: “What was unique and extraordinary about Blondell was her inclusivity, her sense of existing comfortably in many worlds. She certainly drew on the cultural roots and background of being a Black woman as her source and inspiration but she was never afraid to expand her vision and transcend labels.”

The exhibit, co-curated by the Getty Research Institute’s Kristin Juarez, Rebecca Peabody and Glenn Phillips, and the catalog are the first presentation by the GRI’s African American Art History Initiative. If you can’t get to Art + Practice before the exhibit closes, take a virtual tour.

Wouldn’t it be great if the exhibit could come to New York City, where Cummings lived, worked, danced and enjoyed time with her friends? In the meantime, the book is available here.