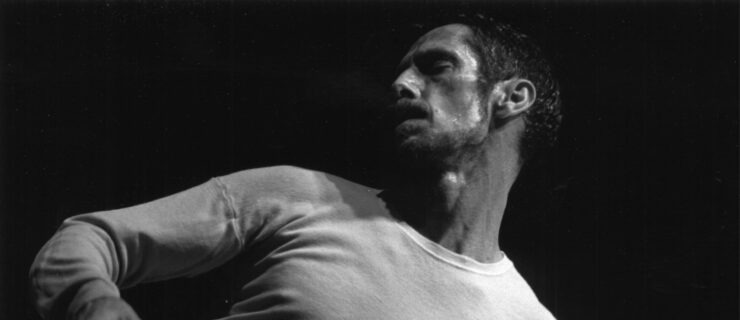

Remembering Blondell Cummings (1944–2015)

A dancer/choreographer who crossed over from modern to postmodern, from the black dance community to the avant-garde community, Blondell Cummings was a riveting presence onstage and a steadying presence offstage. She died of pancreatic cancer last Sunday, Aug. 30.

Cummings grew up in Harlem; she attended NYU and studied at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance. As a dancer/choreographer, she created dozens of solo and group works often touring to Asia or Africa. She was profiled, along with eight other choreographers, in the Michael Blackwood documentary Retracing Steps: American Dance Since Postmodernism (1988) and was included in the PBS series Free to Dance, about black choreographers within the modern dance field.

A founding member of Meredith Monk’s The House, Cummings made a vivid impression in Monk’s Education of the Girlchild (1973). She also appeared in Yvonne Rainer’s film Kristina Talking Pictures (1976). She had a strong presence and a keen focus in every onstage action. Originally a photographer, she developed a type of movement that stuttered like a stop-action film, contained and explosive at once. She used this discovery when performing in The Photographer/Far From the Truth (1983), the collaboration directed by Joanne Akalaitis and choreographed by David Gordon that inaugurated Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival.

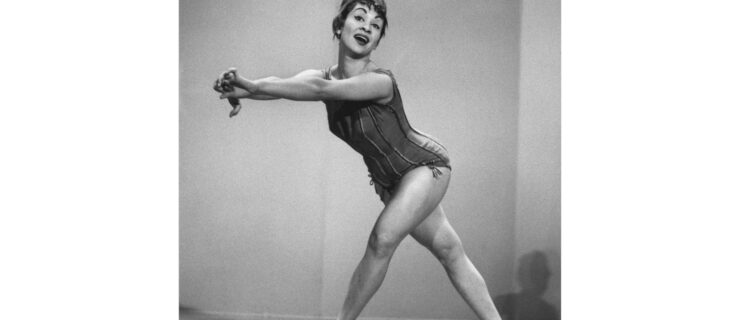

Her solo Chicken Soup (1981) will forever be remembered by those who saw it. Joan Acocella wrote this about it The New Yorker:

“In 1981 Blondell Cummings made a dance, Chicken Soup, in which, while scrubbing a floor on her hands and knees—an act of exemplary realism—she would repeatedly break off, rear up, and shake, in jagged, convulsive movements, as if she were in a strobe light. Then, with no acknowledgement of this interruption, she would go back, serenely, to scrubbing the floor. This strange back and forth made the piece very interesting psychologically: the floor-scrubbing so homey and soapy and nice (Cummings wore a white dress), the convulsions so violent and weird. Was this woman happy, doing this domestic task, or did she hate it so much that she was going crazy? Then there was just the formal interest: the texture, the tension.”

Acocella goes on to say that the dance was interpreted by some as depicting a black domestic working for a white household. But for Cummings, it was just about being a mother taking care of things in her kitchen. In fact, Blondell once told me that the title was going to be Black Bean Soup, but our friend Barbara Roan told her if she wanted it to be universal she should change it to Chicken Soup.

When Ishmael Houston-Jones came up with his brainstorm “Parallels,” the 1982 series at Danspace that opened up downtown dance to African-American choreographers, Cummings was one of the few who had already broken into that world.

Caring deeply about politics and culture, she collaborated with Filipino writer/activist Jessica Hagedorn on the hard-hitting multi-disciplinary production, The Art of War (1984) In her New York Times review, Jennifer Dunning praised Cummings’ “rare physical acting” and wrote that the piece was “hard to look away from.”

Blondell’s values stayed true to the mission of her cross-cultural arts collaborative, Cycle Arts Foundation, which was to bring artist and audience together to focus on “the poetics of the human condition.” She made pieces for student groups at Hunter College and The New School, and for Philadanco. But Chicken Soup remained her signature work.

She toured often to Asia and Africa. If you knew her, you were constantly learning new things about her past. When Blondell and I went to see Bill T. Jones’ musical Fela!, about the Nigerian singer/activist’s days of tumult in a Lagos nightclub called The Shrine, she casually mentioned that she had been to The Shrine and had met Fela Kuti there.

I believe her last public appearance was on the “Fridays at Noon” series at the 92nd Street Y Dance Center last March. She asked Edisa Weeks to show a work in progress and then gathered a panel of diverse experts—for example a social worker, a scientist, a visual artist—to describe their perceptions. When, at the end of the session, she showed the film version of Chicken Soup, the audience was mesmerized.

On Facebook there’s been an outpouring of love and respect for this woman who crossed genres, cultures, and populations. Here are some other memories that came through email or phone calls:

Joan Finkelstein, director of Harkness Foundation for Dance: “Blondell had what I call a ‘questing mind’—she was extremely thoughtful and considered. I served on the Bessies committee with her for a number of years and always learned from the insightful way she spoke about choreography and performance. Her deep humanism informed workshops she crafted to help dancers and non-dancers alike feel more whole, more connected with themselves and each other. As a performer, she was an electric presence and a beautiful mover. As a choreographer she broke through expected norms to find her own unique original form.”

And this from Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, artistic director of Urban Bush Women: “Blondell and Dianne McIntyre were the first African American women I saw doing experimental work rooted in a black experience and identity. They were pushing the form. It gave me courage, a possibility to see ways of creating and thinking and doing that I hadn’t seen.”

Later when celebrating the 20th anniversary of UBW, Zollar invited Cummings to teach Chicken Soup to some of her dancers. “I wanted another generation of dancers to see the power of the work and know the history of innovation in our field, particularly black female innovation.”

One of those UBW dancers was Marjani Forté, who said, “Chicken Soup was score building, a kind of improvisation that I realized later I would be doing the rest of my career with my collective Love/Forté. It was the first time I was performing and reflecting on my lineage—learning how to braid hair with my mom, snapping peas or catching fish. There’s a moment on the rocking chair with a stream of gestures that are coming from things that happen in the kitchen. It was a profound experience I could only understand in hindsight. I am currently doing conjuring-based improvisation, creating or recreating an environment and expression. In Chicken Soup it was frying chicken or making cornbread in a cast iron skillet. Acting doesn’t work; you have to be invoking the memory.” After a pause, Marjani said of Blondell, “She supported all of my work.” Many of us will recognize that sentiment; we were blessed by her friendship.

Blondell had talent, moxie, depth, a kind of poetics of cultural awareness, and unfailing kindness and good cheer. We will miss her.

A memorial service will be held at New York Live Arts on Sunday, October 4 from 5:00 to 7:00. Blondell wanted to have a bench named for her in Central Park, so the family has asked that, in place of flowers, contributions be made toward the bench. Blondell’s sister, Gaynell Cummings, will receive the donations. Her address is 201 Washington Park, Brooklyn, NY 11205.