This New Book Explores a Dancer's Identity After a Career-Ending Injury

For dancers, few things are as worrisome as the thought of a career-ending injury. But when that nightmare becomes a reality, how do you readjust to life without the part that made you whole? And what can you uncover in this fight to discover your new identity and place in the world?

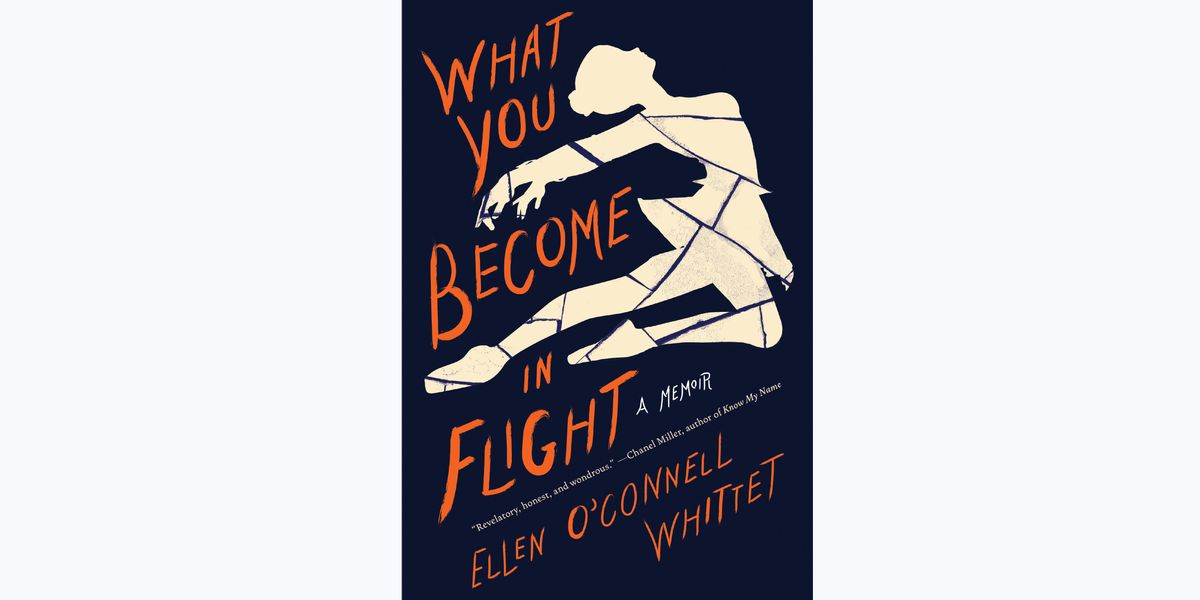

These questions and more serve as the basis for What You Become in Flight, a new memoir by Ellen O’Connell Whittet. When numerous injuries finally prevented her from pursuing ballet professionally, she began to analyze the role dance had played in her life, and the hole it left. Throughout this journey, she uncovered many truths that were swept away by the beauty of ballet: her troubling eating disorder, a lack of consideration for her body’s limits, and the ways in which the world of dance values and treats women.

Ahead of the book’s release, O’Connell Whittet spoke with Dance Magazine about writing her raw memoir and the journey she’s taken post-injury.

After being told you wouldn’t be returning to dance, what went through your head?

Looking back, I think that I didn’t realize the momentousness of it. I knew that it was different from other injuries: It was sort of a continuation of a series of back injuries that I already had, and probably should have paid attention to more and differently than I did. In the moment, I just thought, “Okay, well, I’ve overcome back injuries before.” But when I realized that wasn’t possible, I felt really agitated and angry at myself for having let it get that far.

The topic of identity is heavily weaved throughout your book. How did you begin to find your identity without dance?

If you see your identity as something that has to do with movement and physical expression, then the immobility of being injured is really disorienting. What I did instead was read, which was also something I always loved. And reading allowed me the same escape where I was able to fully inhabit another world, a world that felt like reality.

Throughout the book, you uncover ways in which focusing so heavily on dance throughout your adolescence made you neglect your body, including in the outcome of an eating disorder. What did your healing process show about the world you’d grown up in?

It’s a really patriarchal and hierarchical system that I never thought that I had the power to question. And it’s because I didn’t feel that I had the power to question it that I think it had such a profound toll on my body.

Many eating disorders come from something much deeper than just the desire to look thin; it comes from the desire for control when you have lost control in other ways. I would probably want to tell my younger self to have a lot more compassion for the reasons I was doing it. And also to know that recovery is not linear.

And what would you tell dancers who have, like you, sustained a career-threatening injury, and suddenly feel like they’ve lost the person they were?

I would say that you are more than what someone tells you your body should be able to do. Think about what else you love to do that doesn’t feel like such a struggle all the time.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

I hope that it helps them feel softer towards their younger selves. And I hope that they’re able to see the ways dance is complicated. Because it is so beautiful and so fun. But it can also be damaging or dangerous when people don’t pay attention to the things that they are and are not able to do in dance. I hope it shows readers that our bodies change as we age and as we go through puberty, and there’s not really much of an outlet to talk about that. So I hope that they’re able to think about their own journeys with their bodies.