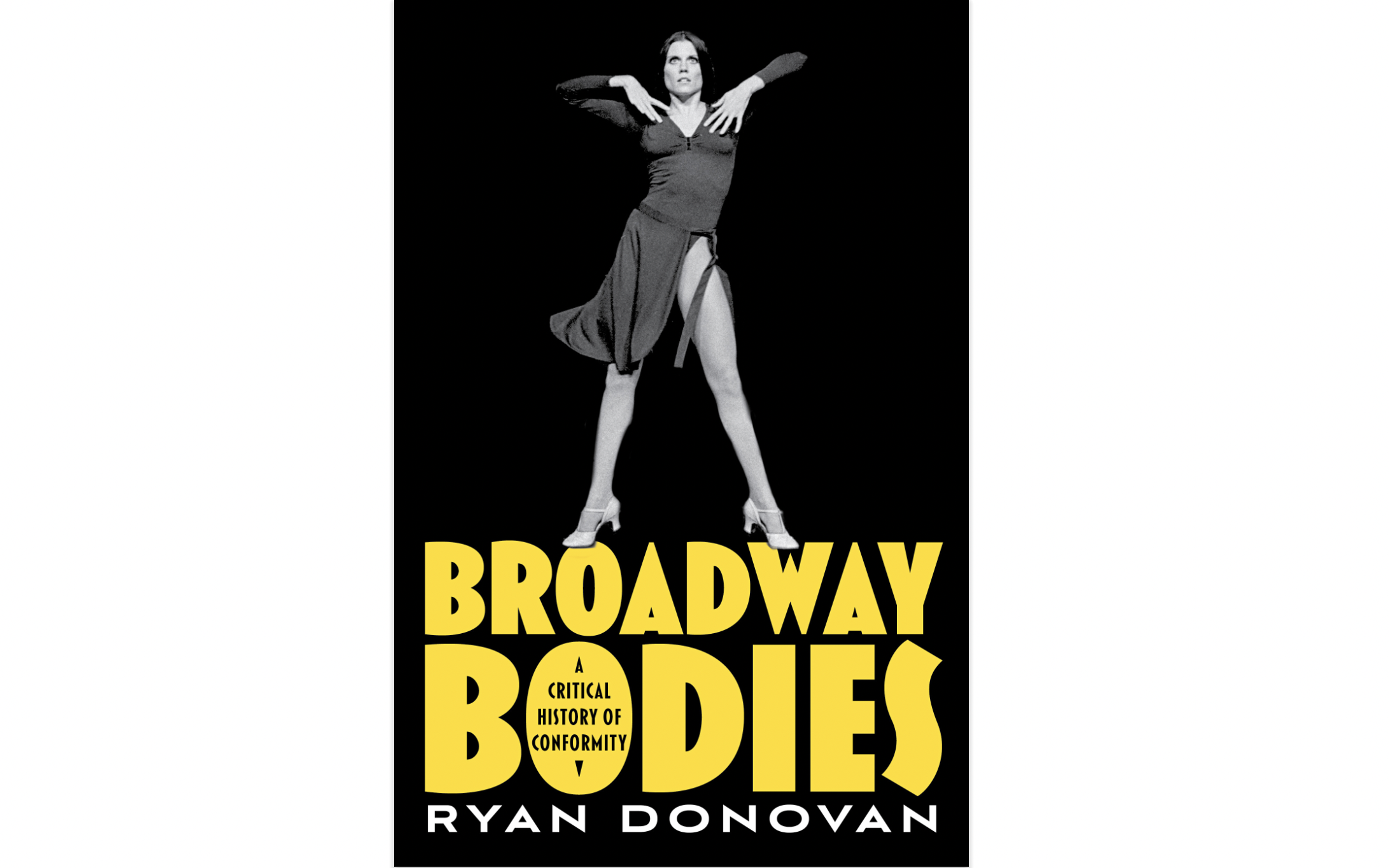

The Body Politics of Broadway: An Excerpt From the Recently Released Book Broadway Bodies: A Critical History of Conformity Sheds Light on Musical Theater’s Longtime Fixation on Physique

From Broadway Bodies: A Critical History of Conformity by Ryan Donovan. Copyright © 2023 by Ryan Donovan and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

I lied about my height on my résumé the entire time I was a dancer, though in truth I don’t think the extra inch ever actually made a difference. In the United States, 5’6″ still reads as short for a man no matter how you slice it. The reason for my deception was that height was frequently the reason I was disqualified: choreographers often wanted taller male dancers for the ensemble and listed a minimum height requirement (usually 5’11” and up) in the casting breakdown. More than once, I was disqualified before I could even set foot in the audition because I possessed an unchangeable physical characteristic that frequently made me unemployable in the industry.

I was learning an object lesson in Broadway’s body politics—and, of course, had I not been a white cisgender non-disabled man, the barriers to employment would have been compounded even further. I wasn’t alone in feeling stuck in a catch-22. Not being cast because of your appearance, or “type” in industry lingo, is casting’s status quo. The casting process openly discriminates on the basis of appearance. This truism even made its way into a song cut from A Chorus Line (1975) called “Broadway Boogie Woogie,” which comically lists all the reasons one might not be cast: “I’m much too tall, much too short, much too thin/Much too fat, much too young for the role/I sing too high, sing too low, sing too loud.” Funny Girl (1964) put it even more bluntly: “If a Girl isn’t pretty/Like a Miss Atlantic City/She should dump the stage/And try another route.” Broadway profoundly ties an actor’s employability to their appearance; when an actor enters the audition room they put their body on the line: do they have a Broadway Body or not? A Chorus Line’s “Dance: Ten, Looks: Three” memorably musicalizes this moment when the character Val relates how her appearance prevented her from booking jobs until she had plastic surgery.

The dominance of what I call the Broadway Body—the hyper-fit, muscular, tall, conventionally attractive, exceptionally able triple-threat performer (one highly skilled in acting, dancing, and singing)—became Broadway’s ideal body as the result of a confluence of aesthetic, economic, and sociocultural factors. The Broadway Body is akin to the ballet body since it too contains the paradox of remaining an unattainable ideal since even those who come close to the ideal must still strive for it, too. Dancers internalize this quest for perfection and know it well.

In theatre, the Broadway Body ideal sets unrealistic standards enforced by industry gatekeepers—from agents and casting directors to producers and college professors. That appearance matters for performers is old news (the Ziegfeld girls were not all chosen for their dance talent back in the 1910s), but Broadway’s pervasive body-shaming is only beginning to be openly discussed in the industry itself. A 2019 study found that two-thirds of performers had been asked to change their appearance, and that 33% of those had been told to lose weight. As a result of the pressure to look a certain way, a small industry of Broadway-focused fitness companies like Built for the Stage and Mark Fisher Fitness sprang up in response.

Backstage noted that Mark Fisher Fitness “is particularly popular among those in the performing arts community looking to get a ‘Broadway Body.’” Other theatrical press picked up on the idea; an article in Playbill asked, “Who doesn’t want a Broadway body?” The Broadway Body is not merely a marketing ploy but a concept grounded in an appearance-based hierarchy. Even some notable Broadway stars capitalized on the connection of Broadway and fitness: in the 1980s, original West Side Story star Carol Lawrence released a workout video titled Carol Lawrence’s Broadway Body Workout, Broadway dancer Ann Reinking wrote a book called The Dancer’s Workout, and even six-time Tony Award winner Angela Lansbury got in on the game by releasing a workout video called Angela Lansbury’s Positive Moves.

The ever-increasing demands of performing a Broadway musical eight times a week necessitate some of the changes seen in Broadway Bodies, from notably higher technical demands placed on dancers to challenging vocal tracks. Artistic choices carry economic implications in commercial entertainment. The wear and tear on the body caused by the repetitive nature of performing a musical eight times a week increases the financial pressure and the physical toll for performers; life offstage becomes about staying fit to prevent injury and staying ready for the next job. Performers must pay more attention than ever to their bodies to remain competitive and employable.

Because the number of spots in the chorus typically outnumber speaking roles, Broadway’s bodily norms most often adhere to the body fascism of the dance and fitness worlds, which strictly regulates and disciplines the appearance and behaviors of the performer’s body into thinness. But these norms do not only impact those in the ensemble: the New York Times reported how Dreamgirls (1981) star Jennifer “Holliday’s weight fluctuations were often the subject of tabloid fodder, but much of the cast felt the pressure to be unrealistically thin,” including Holliday’s co-star Sheryl Lee Ralph, who “realized she was wasting away” due to this pressure. The emphasis on thinness comes at a cost to performers. On Broadway, casting is the site where these concerns come to a head. Even though there is a newfound awareness around the dangers of promoting thinness at all costs, it remains all-too-common for performers, especially dancers, to be told they are somehow inferior because of their appearance.