Are You Still a "Dancer" After You Retire?

Every dancer knows deep in their heart that dance is only a temporary profession, yet we devote our lives to it anyway. We feel called to it.

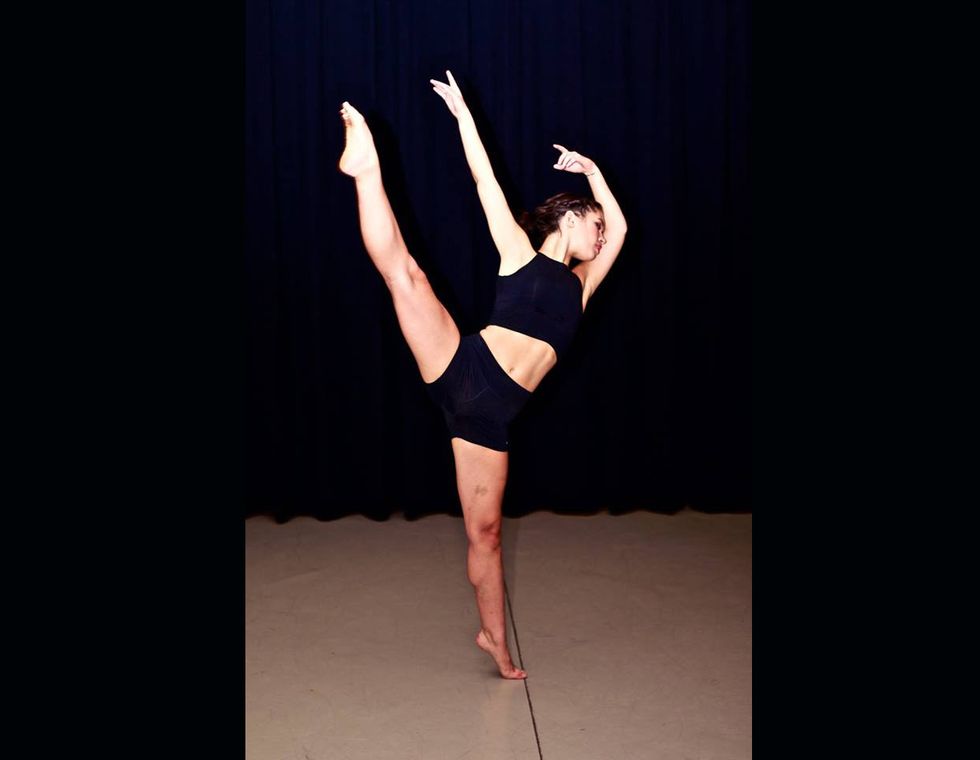

I never felt like I had a choice; I could not imagine doing anything else with my life. I started training at 3, and became immediately obsessed, grand jeté-ing down grocery store aisles forevermore. I described myself as a dancer before even thinking of myself as female, bisexual, American, feminist or teacher.

The phrase “I am a dancer,” is such a source of masochistic pride that I am not sure it reads to people outside the performing arts community, but it is often the only way we can see ourselves.

Growing up, I did all the dancer things. I went to intensives every summer, I paged through Dance Magazine longingly, waited anxiously for new packages from Discount Dance Supply, counted down the minutes to performances. My sweet 16 was even at Chicago the Musical because I was, and am, a Fosse fanatic. In college, along with dance, I double majored in psychology but was usually I was watching videos of Sylvie Guillem on YouTube in the back row.

I was never a confident dancer. For whatever reason, I was always distracted by a fear of inadequacy, a hesitation that definitely read in my performances. Dance was a profound source of joy but caused me just as much pain; it led me to years of boomeranging between anorexia and bulimia, and crippling self-doubt.

“Dance was a profound source of joy but caused me just as much pain.”

I could never fully believe anyone who told me I was talented, or that I had a great run-through, or that I had beautiful lines. I was convinced that everyone was participating in a polite conspiracy to avoid hurting my feelings, that no one dared tell me to give it up. I believed that I got into intensives and internships and colleges by luck or SAT scores over my artistic abilities and hard work.

After college, I spent a few months gigging in New York City doing the downtown dance thing: tiny black box theaters and site-specific work with obscure choreography that your non-dance friends do not “get,” performances done for exposure instead of compensation. I was perfectly content to work three jobs to ensure that I could dance forever.

When I booked a cruise line contract, I was thrilled to finally feel like a “professional dancer.” Halfway through rehearsals, I stress-fractured my left foot in three places and was immobile for eight months.

Just like that, I could not bear weight, let alone dance. I can say without the faintest hint of hyperbole that it was devastating. No words exist to fully explain the pain of feeling trapped in a body that could not dance. Dance was my outlet for the good, the bad, and the ugly, and at 22, I had never fully cultivated any other form of expression.

When I was finally released from physical therapy and rehabbed with Pilates, I was fully intent on returning to dance, not just because I wanted to, but also because I didn’t believe I had anything else to offer.

I started my Pilates certification with every intention of it just being my day job. I had never enjoyed Pilates until my injury; it felt like the cross-training you have to do before you can get to the phrase-work in class. But I was really, really, bad at waitressing, so I had to figure out some way to support myself financially. Dance fed my soul, but didn’t help me buy actual food to feed my physical self.

“While teaching Pilates I felt smart, strong, expert, necessary, loved—things I was unable to receive from dance.”

Immediately after finishing my equipment certification in Pilates, I got an opportunity to dance in Israel and lunged at it. I thought this was my big break—and in hindsight, it was the best dancing I’ve ever done. I pushed my physical boundaries and I could tell that I was making progress artistically.

At the same time, I would leave the studio each day depressed. I was lonely and isolated in a foreign country, and while the other dancers were lovely, they didn’t make me any less sad. I started to realize that dance wasn’t enough to make me happy anymore, because I was doing the best dancing of my career and it wasn’t enough. After giving it a few months of crying myself to sleep, I came home.

I no longer felt as resilient when I got cut at an audition. Apart from project-based work with friends, I stopped actively pursuing auditions or taking dance classes with any semblance of regularity. I started teaching Pilates. I was awful at first. But with each class and client, I improved. The more I learned, the more fascinated I became with teaching. It was clear to me that I was on an upward trajectory, whereas a lifetime of dance had made me believe that I’d never be good enough. While teaching I felt smart, strong, expert, necessary, loved—things I was unable to receive from dance, my own traumas blocked me from receiving any of those things from it.

As I taught Pilates more and danced less, I felt a new part of my identity growing. I had honestly never had outside interests before—dance was the only thing that had ever existed. At the time, I felt guilty not spending my time dancing. I felt like a quitter.

I remembered judgements I had made of the talented girls who slowly distanced themselves from dance in favor of more reliable professions, thinking them mentally weak, not determined enough, even lazy. I would get annoyed if someone who gave up described themselves a dancer. The title of dancer demanded the drive to constantly earn it. I did not feel I was permitted to claim that honor anymore.

While I was devoting my time to teaching, talented dancers I trained with went on to Broadway, Radio City, Complexions, Sleep No More, “So You Think You Can Dance”—and I felt like a failure, even though I loved what I was doing. When clients inquired, “You are a dancer, right?” I’d freeze for a moment, not knowing what to say. What am I now? When you spend 24 years of your life answering that question affirmatively, it’s unsettling to be unsure if you’re “allowed” to call yourself a dancer.

When I first moved to New York, I was in class every day, spending all of my (little) money on expensive Broadway Dance Center and Peridance classes and struggling to pay rent. Then when I finally started making a livable income, I couldn’t be bothered to make the trip to Midtown for class.

“When clients inquired, ‘You are a dancer, right?’ I’d freeze for a moment, not knowing what to say.”

Then, out of nowhere, I got an opportunity to dance for Tracie Stanfield, a choreographer I’d long dreamed of working with. The external validation that I’d never been able to trust finally came. But with it came more confusion. I had come to terms with the idea that I wasn’t good enough and that I never would be, and I’d let that close the chapter on dancing professionally.

If this opportunity had come five years earlier, I would have been ecstatic. Truthfully, tears did come to my eyes when I opened the email inviting me to perform in her summer concert, but it wasn’t the excitement I always assumed booking “the job” would feel like—it was an “Oh, thank God, my art and I are actually of value to someone.”

Our first rehearsal together was a blur. I did not have time to reflect about how I felt because there was so much information. But as the days passed I found myself staring at the clock, thinking about my Pilates classes, my schedule, and inevitably comparing myself to the other company members who had much sharper technique as a result of consistency in their training.

For the first time, though, I didn’t feel inadequate next to beautiful movers; I was very aware that their prowess came from the work they were doing that I simply was not. Eventually, after several conversations about how to get the movement out of me and trying to get me up to speed with the other performers, Tracie let me go from the project. She told me she had every confidence I had “it” in me, but that I was not working on my craft. She told me to stay in touch and get in her class regularly, but I found myself not wanting to put in that work.

Somehow, I believed her when she told me I had potential. I realized that my mediocrity in this piece was not lack of talent, but lack of will. I was resisting because I had new callings: teaching fitness, rehabbing other people’s injuries, building other people up. I did cry—but not tears of devastation. My tears were of relief, a very heavy weight was lifted.

The grief I’d felt for the past few years as I wrestled with the constant voice in my head asking, “Can I dance? Do I even want to dance?” lessened, and I found some closure.

Getting cut from the show was ultimately a gift. Dance has been with me since age 3, and at 27, while I’ll never say never, I finally have the courage to admit that dance is not my priority anymore. I do not want that life anymore. It’s not of interest to me to detract from my teaching work to devote time to training for it. It still feels strange to write those words.

So, am I dancer? I think the answer is yes. I will always have this bittersweet relationship with dance, since it had been the driving force of my entire life. I do not have conscious memories of life before I danced. From a neuroscience perspective, the stimulus for virtually all of my associative learning was dance. All the brain development I’ve experienced was based on a dancer’s experience of the world. My neurons, after 24 years of dancing, have been wired so that a dancer’s perspective and habits are automatic and deeply rooted.

A few years of teaching Pilates is not, and I doubt will ever be, enough to disconnect that patterning. I don’t think I could release that identity, even if I wanted to be someone else.