How Circa Contemporary Circus Pulls Off the "Impossible" Onstage

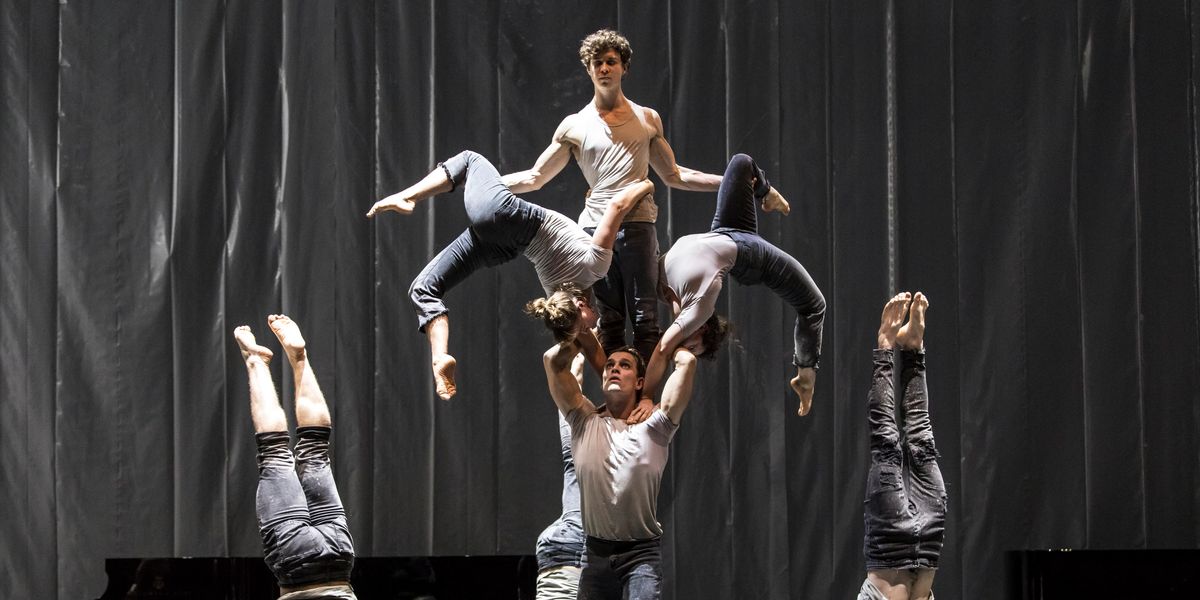

Watching Circa Contemporary Circus is a nail-biting experience. The acrobats climb the limbs of their fellow cast members, fly through the air without wires or ropes, and create human architecture that leaves audience members’ mouths agape. The venues they perform in—from Jacob’s Pillow in Massachusetts to the Barbican in London—grow abuzz with anxious energy. It’s impossible not to wonder, “How do they pull it off?”

How they create the work

The Australian company’s process begins with a series of improvisational provocations given by artistic director Yaron Lifschitz. “He often comes to us with an image, and divides us into groups to create it with our bodies,” says ensemble member Caroline Baillon.

Her colleague Marty Evans adds that this improvisational element is crucial to the ethos of the company. “It’s important that everyone moves the way that they move,” he says. “Otherwise, it won’t work. The show comes from the natural tendencies of our bodies, supervised and stimulated by Yaron.”

This strategy stems, in part, from the specific acrobatic skills of the artists. “Often the structures we develop are tricks we are already capable of,” Evans says. “We find a way to make them fit in the world we are creating.” With such a collaborative process, Lifschitz says he does not consider himself a choreographer.

What it takes to do the impossible

In one tower balance called “The Batman” (a crowd favorite), Evans stands on the ground as the base. On top of his shoulders stand the feet of a man referred to as “the middle,” as well as two female flyers on either side, balancing in handstands also on his shoulders (yes, you read that right). The middle holds on to the upside-down flyers’ legs while they arch into double attitudes, making an image that loosely resembles the Bat-Signal.

“I’ve learned to build connections between a base and a middle so the feet sit comfortably on my shoulders without any wobble at the joint,” Evans says. “Everyone’s feet are different, so the way I move changes depending on who is on top of me, and the things they need to balance.”

Baillon’s experience as a flyer reflects the other end of that exchange: “If I’m out of balance, I need to push on my base, and use pressure to communicate where I need them to move me.”

The role of fear

All of Circa’s work is done without wires or harnesses, meaning the danger is very real. For Baillon, whose circus training began at 7 years old, fear is a challenging but necessary component. “It stops me from doing things that could potentially injure me,” she says. “But at other times it can be a block that needs to be managed.”

In the end, her sense of security comes down to trust. “The more I work on something, the less scared I feel because I learn to trust my body,” she says. “The closer I get to my base, and the more trust I build with them, the safer I feel.”

For Evans, it’s a bit more complicated. “I won’t do something that I’m afraid of,” he says. “A flyer may be able to do a skill they are scared of because they trust their base, but I can’t do that because I’m not the one in danger. I’m the base they are trusting.”

To get to a place where the artists can feel confident that they are safe, they spend months training and working through progressions for each trick. If that confidence doesn’t eventually come, the artists are always free to communicate their physical limits with Lifschitz.

“Every human should have the right to go to work and be looked after,” says Lifschitz. “They will take risks, but there will always be comparative safety. There is a strong shared culture here where we never ask people to do things they are uncomfortable with.”

How they avoid injury

Even while managing these dangers, injury is obviously still a possibility. To avoid it, the ensemble has a standard three-hour call before each performance. The first hour is an individualized warm-up in which the artists work through the specific needs of their own bodies. Then, during the second and third hours, they run through group and partner skills to make sure they are solid before doing a group improvisation with the music that will be used in the show.

“The big injuries come from a lack of control, but other injuries come from overuse and incorrect use,” says Baillon. “The preshow warm-up with TheraBands and individual exercises help avoid that.”

Advice for dancers who want to be acrobats

For artists looking to reroute their dancing careers to something more acrobatic, Baillon has three words: “Don’t restrain yourself,” then adds, “What you have from your dance experience can bring something amazing to circus.”