Dancer Crystaldawn Bell on the Unconventional Process of Crafting Solos with Choreographer Robert Moses

When choreographer Robert Moses recently asked longtime dancer Crystaldawn Bell to work on a new solo with him, it wasn’t his first time proposing a rather unconventional creative process. Over the past decade, the two artists have created a handful of pieces together, with Moses as choreographer and Bell as collaborator: Typically Moses presents Bell with a concept and some source material—usually lots of videos of phrases from past classes and rehearsals and written directions. Bell stitches together whatever she’s inspired by, along with her own movement, and Moses directs, edits, and makes changes.

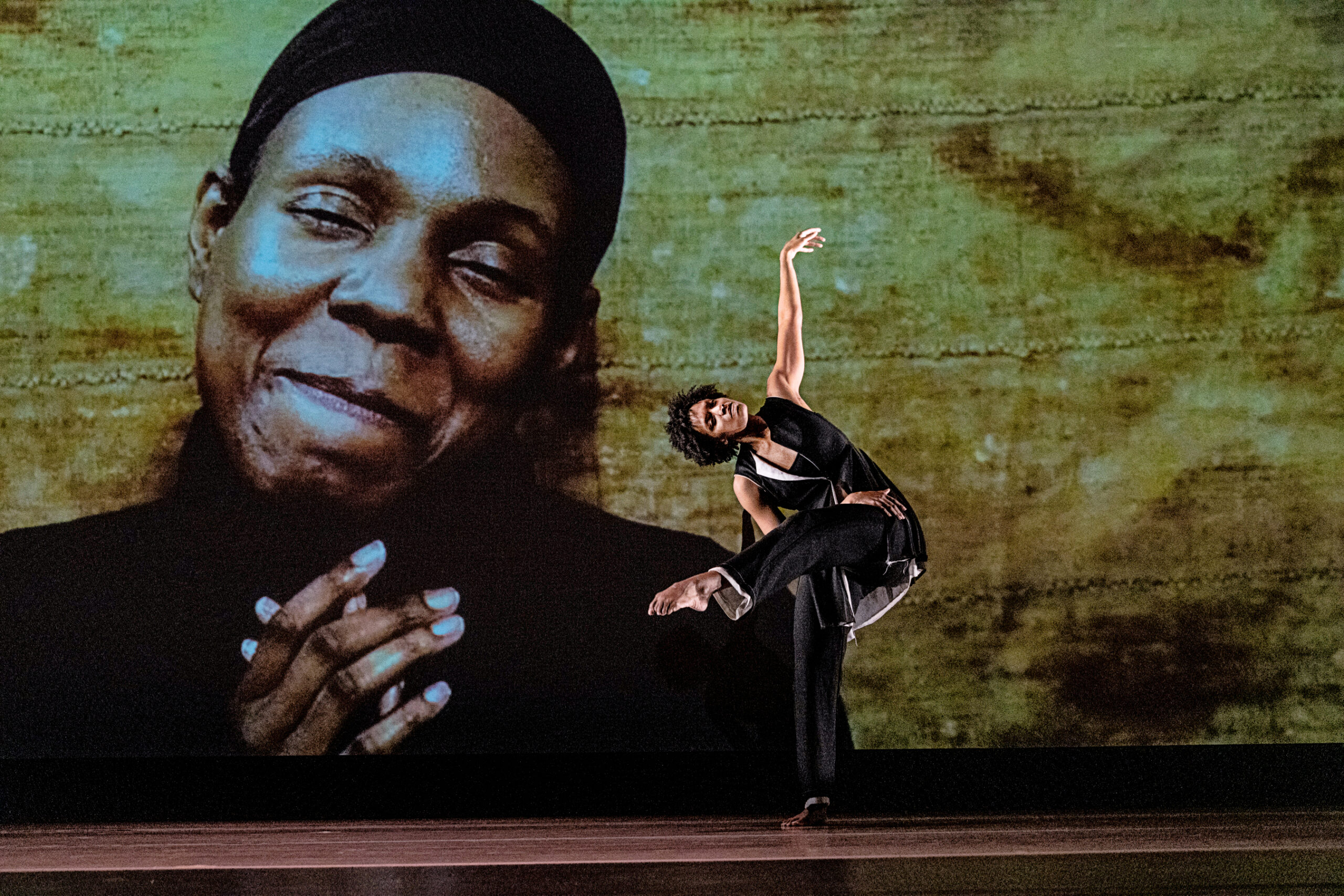

The latest result of their collaboration: Can’t I Keep Just One?, which premiered in March in San Francisco as part of Robert Moses’ Kin’s spring season, deals with truly harrowing subject matter. Performed in front of an excerpt of the video From Slavery to the White House, originally an evening-length production written and directed by Moses’ niece, Monica C. Moses, Can’t I Keep Just One? tells the story of an enslaved woman, Cora, who must go to great, horrifying lengths to ensure her baby is not sold, as her other children have been. “It’s heavy, but I’m glad it’s on the table,” says Bell. “I’m glad Robert is willing to go there—to make people think; to make people uncomfortable. He doesn’t just make pieces to make pieces.”

When Robert sends me videos, it’s like going into a closet of everything you’ve ever wanted and being like, “I’m gonna wear this jacket.” Often I will learn things and then splice them move for move, building my own transitions so that I’m a part of the piece instead of just reiterating what he’s already created.

I love gestures. Because I can add legs to them, I can make them faster, I can make them slower, I can repeat them. Sometimes, I tie them to words that the actress in the video is saying. Because it’s a lot to watch; it’s a lot to listen to; it’s a lot to comprehend. So I try to pull movement that can aid in the storytelling.

It’s not about the technique. It’s not about showing that I’ve been training since I was 3 years old—”Look, I can balance on one foot.” It’s about, how are you going to gel with the audience? That is the most important thing, making that connection.

I did a piece a few years ago [with Robert] called Black Woman, Black Girl. That was the first time that I was like, “Oh, it’s an emotional thing we’re trying to do here.” We’re not trying to wow people in the audience with dance; we’re trying to make people leave the theater changed.

To have Robert’s movement and splice in just a little bit of me, like a comma, it doesn’t feel like performing. It just feels like I’m having a conversation. I haven’t been able to experience that with any other company or any other performance. I’m literally going through something every time I do something with Robert. It’s deeper than dance.

It feels almost icky to bow at the end, and get the applause. You just want to let it resonate with people. It’s tough to put myself in the character’s shoes, and think that I am where I am today because of the sacrifices that other people before me were able to make.