What It's Like To Accompany Dance Classes…When You're Also a Dancer

My name is Jonathan Matthews, and I wear a lot of hats. One is being a dancer; another is being a musician. A third is attempting to call myself a professional at both in New York City.

Accompanying dance classes is one of those attempts.

Some accompanists scramble into the studio with disintegrating folders, barely able to keep their piles of sheet music from flying out, one unordered page at a time. Others are human jukeboxes.

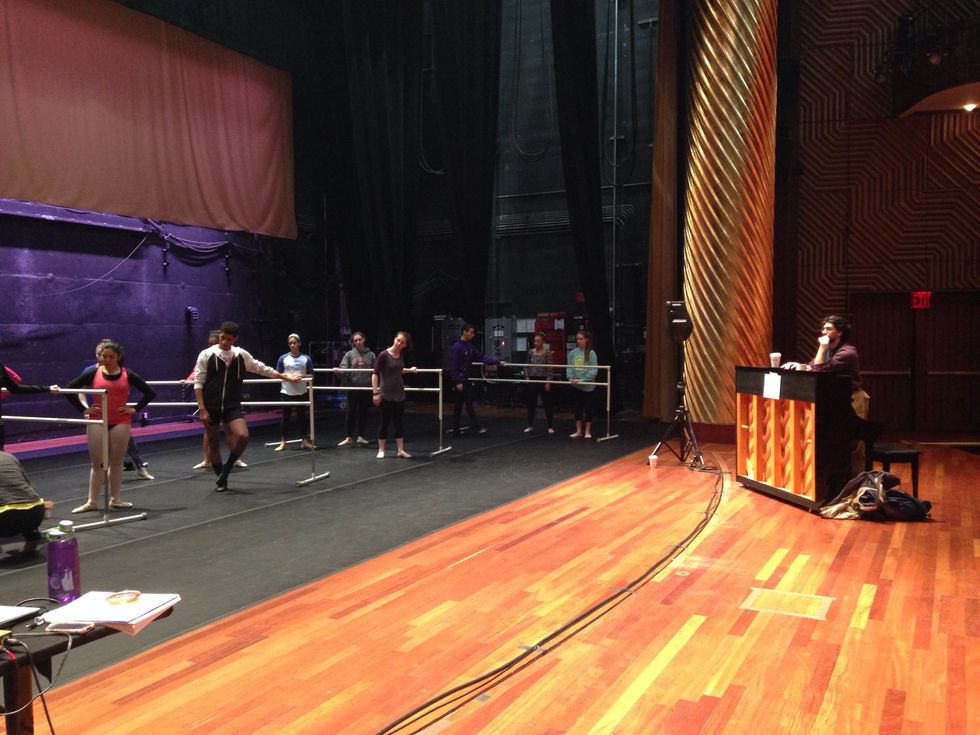

The author, accompanying a class onstage. Photo by Indah Walsh, courtesy Matthews.

I spend my long commutes taking screen shots of tunes that strike me as particularly dance-able on my iPod. I learn them and later log them into an ever-expanding word document, arranged into broad categories of meter, from which smaller subcategories emerge including subdivision, genre, and whether they’re ideal for a battement tendu or perhaps something grander.

The truth is that I’m not a very good pianist. I am admitting to this now, just so we’re clear.

I faked playing second violin in elementary school and didn’t even notice when I got switched to viola. I had a band in middle school, but quit taking guitar lessons as soon as my teacher weaned me off power chords for jazz and classical, at which point I was already learning Philip Glass pieces by ear on my dinky Casio keyboard at home, realizing I liked that better.

When I started as a dance major at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, I had a whopping two years of beginner piano lessons under my belt. While there I adamantly signed up for non-major piano lessons every semester, ambitiously hopping between Bach, Chopin, Debussy and Bartók. Building rep was not the point—I knew I would never be a soloist—I simply sought to absorb as many lessons from within the music as I could to build a true relationship with a musical instrument for the first time.

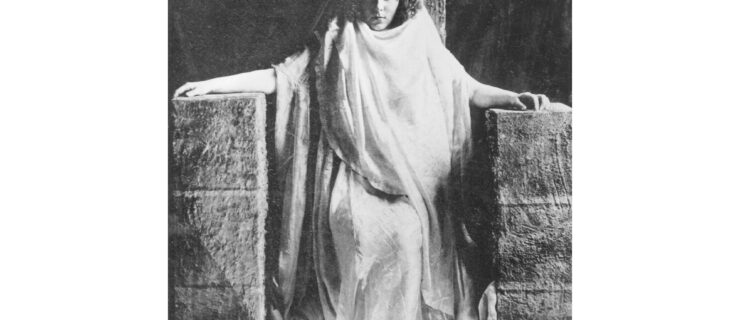

The author dancing in ChristinaNoel & The Creature’s Belly. Photo by Michelle Zassenhaus, courtesy Matthews.

Nowadays, having no time to keep a consistent practice, much of that information has left my hands, but it enabled me to develop a relatively good veil of proficient playing—a relaxed but rhythmically-curious style, way too influenced by Tori Amos and the gamut of ’70s progressive rock for its own good.

I started playing for dance in my second year at Tisch. I had become known in the department as the kid who prettily tinkered on the studio pianos between classes. Slowly but surely my classmates started asking me to compose music for them.

This got me a significant amount of (volunteer) mileage in my last two years as a dance major. Almost every student showing involved me making my way from the audience to the gorgeous red Kawai grand piano in the department’s black box theater. I had no musician friends and to this day don’t understand technology, so I would always play solo piano, which made me a better player and taught me how to be symbiotically supportive with something else happening in the same space.

In a particularly life-changing summer, my ballet professor Giada Ferrone decided I would take part in the first accompanist training module of her summer dance program, Toscana Dance HUB, in her hometown of Florence, Italy.

Accompanying Pamela Pietro’s Future Dancers and Dancemakers course at NYU. Photo by Indah Walsh.

I had flirted with the idea of taking up accompaniment, trying my hand playing for the students of Pamela Pietro’s pedagogy course at Tisch. I wasn’t quite ready, however, for Mark Morris’ former principal pianist and current Barnard dance department music director Robert Boston’s vigorous coaching as I tried over three weeks in the Tuscan heat to build the creative and technical endurance to play for an entire ballet class. But I absorbed as much as I could, shedding habits to generate some semblance of an approach to the work.

By the time I came back, one of NYU’s accompanists was leaving the department, and Pam needed a musician to play on Saturday mornings and mentor the students on teaching with a live musician. Being a newly-improved musician who teaches dance regularly, I never felt more suited for a position. Such was the beginning of my getting paid for what I have come to revere as my most sacred profession.

While I’ve played elsewhere off and on, I have been on the accompanist roster at Tisch since the fall of 2015. The department has one of the most diverse faculties—from Jolinda Menendez’s strict classicism, to Rashaun Mitchell’s personal take on Cunningham, and assorted one-off goodies like when the current senior class auditioned to perform Paul Taylor’s Promethean Fire. I often play for teachers who taught me, which moves me all the more to do my best work and continually improve, as I am still relatively infantile at the practice.

I will admit, this whole dancer/musician duality is a fun fact I tend to bring up in artistic circles when introducing myself. The reactions I get usually go something like, “Wowww, since you’re a dancer, too, you must be, like, the greatest accompanist EVER.” This is horrifically fallacious.

Dancing in ChristinaNoel & The Creature’s but, love. Photo by Michelle Zassenhaus

The other week I was playing for Wednesday morning ballet class with William Whitener, who gave me the note of being too speedy on the petit allegro. (Granted, as a compulsive coffee drinker, I get this a lot.)

After slowing down a smidgen and still getting the note, I looked up and realized the combination had quite a few ballonnés, which require a particularly spacious sort of subdivision that I was not offering. I immediately switched to another piece in 2/4 time, but with less forward drive and more bounce, and all was well (until, of course, the excitement of having solved the problem caused me to speed up again).

This is to say that while the notion of one’s class playing being enhanced by additionally being a dancer is certainly valid, it is an equally opportune trap—one’s being a dancer actually desensitizes you to what is happening in the room. You hear a teacher say “petit allegro,” wait to hear how they sing the movements’ names before deciding it’s a 2/4 or a 6/8, and then you just go. There’s a lot of potential for autopilot here.

This is where some of the best advice I have ever received comes into play: “You gotta treat the dancers like you’re all in a band together.”

James Martin—one of the most energizing ballet teachers one could ever hope to have—slipped that nugget of gold to me. This means looking up, following the teacher’s pulse, but modifying appropriately from the platonic ideal to accommodate bodies working through the material for the first time. If they seem sad, play something cheery. In short, react.

Performing an excerpt of ChristinaNoel & The Creature’s but, love. Photo by Darial Sneed, courtesy Matthews.

If you’re a dancer lucky enough to have taken class with live musical accompaniment, you are likely aware of that player who breaks out their flashiest concert repertoire for exercises as simple as bending your legs over and over again. The greatest relief I have ever sighed was let out upon realizing that great playing does not a great collaborative player make. A great collaborative player is, rather, simply an attentive human.

Accompanying dance is not the same as accompanying singers, which I occasionally do to a lesser degree. When supporting fellow musicians, tradition usually expects the player’s body to be invisible, constructing an illusion, believed by no one, that the sound they are producing just sort of magically exists. Accompanists of bodies in space and time, however, are no less present than their cohabiters. I’ll even learn combinations along with them, if I am so moved.

My playlist often draws on my physical memory. I play a lot of the church tunes I spent nine years in Catholic school processing to. Having rekindled my Irish dance practice with Darrah Carr Dance, I often defer to reels and jigs for petit allegros. Along with my beloved Philip Glass, I’ll dish out scattered showtunes from musicals I was either in or hope to be in someday, and other select favorites I know I personally would love to dance to. In this sense, playing for dancers has become one of the few things that begins to connect my many dots.

Contrary to what old-school teachers might believe, I maintain that it is not the accompanist’s job to hold the class as Atlas carries the Earth on his shoulders, nor is it the dancer’s job to catch every note that is played. It is actually the only way I can imagine the phrase “separate but equal” possibly connoting something positive:

The two forms cohabit the room, simultaneously produced, in the present moment. It is not simply an aesthetic nicety, but a living functional process, in which the musician’s segmentation of time meets the dancer’s modification of motion in space in a wholly intentional manner – a realization I probably would never have had simply as a musician if not for additionally inheriting a heavily Judson/Cunningham-influenced dance ideology from my very own alma mater-turned workplace.