Dance Renegades

Here, we salute the troublemakers, the rule breakers, the artists who turn their backs on convention to push the field in new directions. Every dance artist, in their own way, is a renegade—it takes a certain kind of rebellious spirit to choose this career. But some also have the guts to disrupt the status quo of what is considered “right” and “good” even within the dance world. Dance Magazine chose 10 who particularly intrigue and inspire us. Sometimes they make us uncomfortable. Often, they make us think. Always, we love them for it.

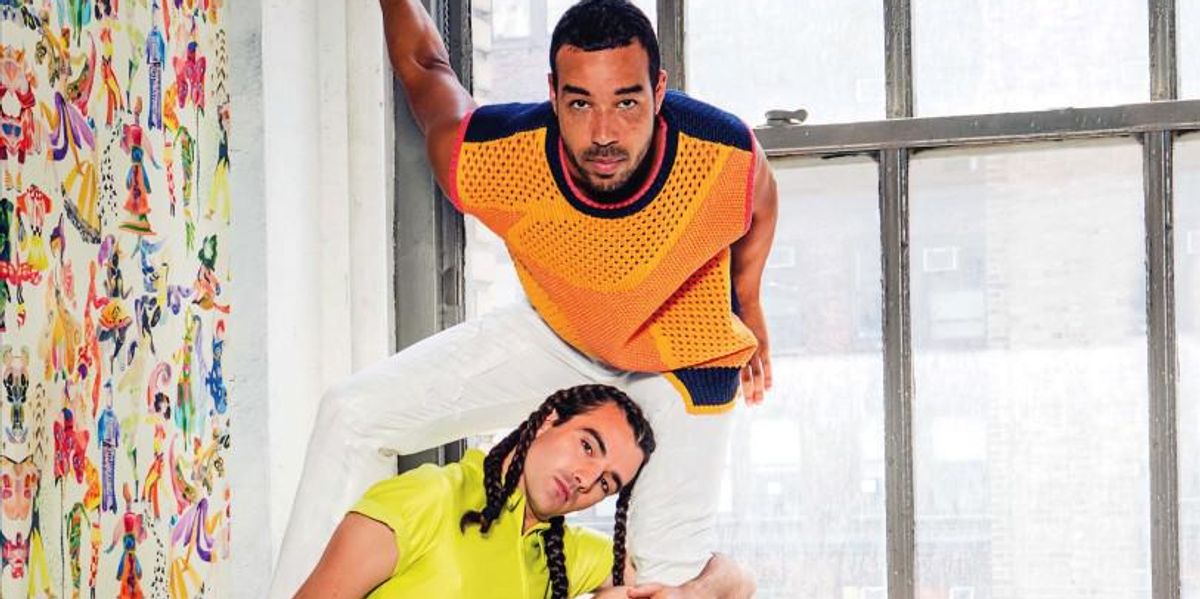

Dynamic Duo

: Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener don’t just break the rules. They break them in a new way each time.

The first rule of being a renegade is that you don’t admit to being a renegade. Like being a rock star or a superhero, it’s a title bestowed upon you by others, admiringly, while you just do what you do. So Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener pass the test when presented with the proposition that they are dance renegades. “I have no idea what that means,” says Riener. “I think it means that we’re not to be trusted.” Next to him, Mitchell concurs: “It means we’re treacherous.”

The two spoke from a residency in upstate New York where, in collaboration with video artist Charles Atlas, they’re embarking on a new challenge: a 3-D dance film. It’s yet another unexpected project from the perpetually curious artists who have captivated the New York dance community with their transition from accomplished dancers in one of the most revered companies of the past century to acclaimed dancemakers in their own right.

Both were members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s last generation of dancers—Mitchell joined in 2004, Riener in 2007, and both drew attention for their astute interpretations of classic roles. They had already started creating work together before the company shuttered at the end of 2011, two years after Cunningham’s death. Their first collaboration, Nox, was based on the writer Anne Carson’s elegy to her brother. The project, with text, projected drawings and non-dance artists, signaled impressive artistic ambition—and a talent for channeling it effectively. “We discovered that we really complement each other physically as well as mentally and artistically,” says Mitchell.

When the Cunningham company closed, an understandable impulse would have been to capitalize on that association. “It could be very easy as former Cunningham dancers to coast on that legacy and create Cunningham-Lite work,” says Claudia La Rocco, a critic and writer who has collaborated with them. Instead, they decided to channel the physical and intellectual rigor of Cunningham but reshape it in their own image.

One might expect renegades to break with the past in flamboyant fashion, but Mitchell and Riener refuse to play that role. Their history with Cunningham is a source of pride as well as something useful to push against. “We have a multifaceted relationship with it,” says Riener, who still teaches Cunningham technique and repertoire. Mitchell agrees. “We recognize that people are always going to contextualize us as ex-Cunningham dancers and in some ways we like to have fun with that,” he says. That may be as simple as donning a Cunningham-esque unitard, or it may be more qualitative—drawing on the precision that gives Cunningham’s work its crispness but using it to blur lines and explore ambiguity.

In the past five years, the two have collaborated on 11 works that are perhaps most notable for having very little in common. That might be the result of letting each space—whether theater, gallery or outdoor setting—shape the mood of a work. It also comes from being unafraid to walk into the creative process willing to embrace whatever comes. “They don’t go in knowing what the finished product will be,” says collaborator Melissa Toogood. As a result, each work has a distinct individuality. Interface, for example, mines the emotions of facial expression, while Way In is an intellectual investigation of objectification. “What I love about how they work is they don’t make either/or distinctions between rigorous physical movement and conceptual ideas,” says La Rocco. The result can ricochet between Jackson Pollock–like spurts of energy and Mark Rothko–like landscapes of contemplation.

In their collaborations, some choreography is credited to Mitchell, some to Riener, and some is shared. Part of divvying up tasks has to do with where they are in their individual journeys. Mitchell, 36, grew up in Georgia and began formal dance training at 15 before earning a BFA in dance at Sarah Lawrence and embarking on a professional career. Riener, 31, was born and raised in Washington, DC, and played soccer until discovering dance at Princeton, where he studied comparative literature. “I think I just had more time to get the dance out of my body,” says Mitchell of his current focus on dance-making. After the Cunningham company closed, Riener sought other performance opportunities with choreographers like Tere O’Connor, Wally Cardona, Kota Yamazaki, Rebecca Lazier and Joanna Kotze. “I wanted to be creatively involved in other people’s dances,” he says.

Regardless of who’s officially heading a project, dialogue flows in all directions, and, inside the studio, there’s a healthy tension of ideas and a casual relationship with any sense of ownership. “One makes something and the other will take liberties to change it the next day, and they’re okay with that,” notes Toogood. But they aren’t afraid to push one another. “They’re questioning each other in a way that’s really generous,” says La Rocco. “You see the physical conversation between them.”

That generosity is helpful when rehearsal is over and the duo, who are romantically involved, retire to their shared apartment in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Yet separating work from leisure can be a challenge. “I don’t think we have very good boundaries,” admits Riener. Muses Mitchell: “Choreographing is a lifestyle,” he says. “The things we do in our downtime also influence the things we do when we’re working.” And the downtime is a rare commodity, given the balance of the opportunities coming their way and the pressures of making a living as freelance dance artists in New York. (Mitchell is an assistant professor at New York University; Riener dances, teaches occasionally and sets Cunningham work on companies.)

In facing that reality, it’s fair to say that all artists are renegades because they trade comfort for creation. Mitchell and Riener epitomize that drive while subverting expectations and balking at the rules of tradition and collaboration. Maybe Riener was right—maybe they shouldn’t be trusted. And that’s a good thing. – Brian Schaefer

Online Oddball: Michelle Ellsworth

Snapping her fingers like a ticking bomb, Michelle Ellsworth enters the stage in Preparation for the Obsolescence of the Y Chromosome, and says, “I don’t mean to make any trouble.” Oh, yes you do, Ms. Ellsworth! The end of men is just the kind of subject that Ellsworth likes to tackle full-on. The choreographer/provocateur is known for her relentless musings on science, culture and technology, as well as her quirky website installations. She explores the relationship between hamburgers and humans in The Burger Foundation, while in The Motivational Video Archive she dispenses such advice as “Don’t Collaborate” and “Dump the Girlfriend.” Her web app Choreography Generator, which accompanies a larger live piece, mixes and matches sound and dance in a box that can be manipulated by the user, addressing the fact that we have all seen the same thing too much. She’s funny, heady and delights in finding odd ways into serious material. —Nancy Wozny

Guerilla Techie: Adam H. Weinert

Deeply invested in what makes American dance American, Adam H. Weinert isn’t above guerrilla action to get a point across. In The Reaccession of Ted Shawn, Weinert asked viewers to download the Dance-Tech Augmented Reality app on their smartphones or tablets, which played videos of Weinert performing Shawn solos when the device was pointed at particular signs and art work in the Museum of Modern Art. It was a covert way to address the fact that MoMA gave away Ted Shawn’s archives after being gifted them in the 1940s. The result activated the past with the here-and-now of the latest technology. The final stage of the project, Without Consent, included contributions from the public. Weinert has the utmost respect for tradition, but is unafraid to experiment with novel ways to share his work. —NW

Throwback Success: Iain Webb

Trendiness has no place in Iain Webb’s repertoire. “When I first got here, I looked at all the companies with a similar budget, and they were all doing more or less the same ballets,” says the Sarasota Ballet artistic director. “I thought, If I were a presenter, what would make me choose a company?” Webb found his niche by focusing Sarasota’s rep around historic one-acts—particularly those by choreographers he’d worked with at The Royal Ballet, like Frederick Ashton—and investing in the necessary coaching to give them authenticity and personality. Not that Webb ignores new creations: In his eight years as artistic director, he’s introduced 123 ballets to Sarasota Ballet’s rep, with 35 world premieres. “I have to be careful we don’t become a museum company,” says Webb. “But I also want to show these great ballets that aren’t performed anywhere else today.” —Jennifer Stahl

Redeemed Bad Boy: Sergei Polunin

When Sergei Polunin abandoned his career at The Royal Ballet in 2012, he complained, “The artist in me was dying.” Luckily, he’s brought that artist back to life. After two years with the Stanislavsky Ballet, he’s gone freelance, partnering stars like Natalia Osipova and delving into film projects, including a documentary about his career, called DANCER. What’s more, he’s launching an organization called Project Polunin in association with Sadler’s Wells to bring together dance, music, film and contemporary art collaborators to create new classical ballets for the stage and film. He also hopes to help fund talented students, and provide them with managers who can advocate for their interests. As Polunin has told journalists recently, he’s tired of being seen as a rebel; he wants to become a role model. —JS

Rock-star Rebel: Steven Reker

Steven Reker doesn’t just make moves to music; often, his moves make the music. The former David Byrne guitarist and dancer has a vision for merging dance, music and theater. In a typical hybrid performance—where a set is never just a set, a dancer never just a dancer—Reker’s musician/dancers might tear up the floor under them to explore the sounds the panels make when waved in the air; shred through modern-dance–style floorwork with an electric guitar hanging from their backs; and accomplish partnered lifts with cords and drum kits as much in the mix as the other dancers. With a 2015 American Dance Institute Solange MacArthur Award for New Choreography at his back, he’s recently formed a new Brooklyn-based band called Open House. The contemporary world can look forward to more movement that sounds as good as it looks. —Candice Thompson

Queer Classicists: Ballez

Some might argue that ballet clings to outdated ideals of gender and sexuality. Not so at Ballez, which rewrites the narratives of story ballets to tackle those very topics using a cast of lesbian, queer and transgendered female-assigned and identified dancers. The idea grew out of conversations—and a pun—artistic director Katy Pyle had with friends in New York’s downtown dance scene. She had always had a deep love for ballet, but grew disenchanted while in high school at University of North Carolina School of the Arts. “I felt restrictions put upon me about the size and shape of my body,” says Pyle. “I loved men’s class, those jumps and turns, and I was like, Why is this not a part of our training? It doesn’t make any sense to me.” So she began work-shopping and assembling material for a ballet. A year later, she started offering ballet classes that prioritized queer bodies, and in 2013, she staged a performance of The Firebird, a Ballez. Featuring a Lesbian Princess and a “Tranimal” dancing classical ballet vocabulary, the show was received warmly: “This Firebird blazes with heart,” wrote Gia Kourlas in The New York Times. A new production, Sleeping Beauty & the Beast, premieres in spring 2016. “There’s something we all love deeply about ballet, and still connect to,” says Pyle. “I feel like the ballet world is missing out by not having us in it. Ballez is a gateway for these incredible performers to be seen.” —Lea Marshall

Thinking Out of the Black Box: AUNTS, SALTA & Others

Today’s audience members are given a chance to do more than just witness: They’re asked to participate. By using nontraditional spaces, a new generation of choreographers has begun offering not just performances but one-of-a-kind experiences.

AUNTS, a roving party of dance performances in New York City, uses lofts, theaters and repurposed buildings to contain a series of dance experiments in which audience members can wander as they please. An AUNTS show can feel like the Wild West of dance: There are few rules, if any. Their aesthetic would have trouble squeezing into even the most avant-garde theater—and that’s the whole point.

On the opposite coast, Oakland-based curatorial collective SALTA hosts performances, parties, happenings and group encounters everywhere from warehouses to cafes. The same performance could be held in two different locations and take on entirely different meanings depending on where it is and who’s present.

Does the use of a nontraditional space make contemporary dance inherently more urgent or relevant? Not necessarily. But, as a co-curator of a similar presenting series called The Bunker, I’ve seen the possibilities for the way it can challenge the static relationship between performer and viewer. At our warehouse performances, the audience can crowd in close, hang back, take photos or talk to each other. They can even walk away. But they don’t. And they certainly don’t doze off in their seats. —Nicole Loeffler-Gladstone

Postmodern Provocateur: Trajal Harrell

Trajal Harrell’s eight-part Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church series has challenged the conceptual temper of the contemporary dance scene. His premise? “What would have happened in 1963 if someone from the voguing-ball scene in Harlem had come downtown to perform alongside the early postmoderns at Judson Church?” By combining Judson minimalism with the flamboyant presentation of street voguing, Harrell has pushed Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto forward to create a unique creative impulse that brings spectacle back to the postmodern stage, once again working to seduce downtown audiences. The avant-garde work has catapulted to prominent venues everywhere from Vienna to Rio de Janeiro to Montpellier, a success that has inspired both younger and more established artists to try to capitalize on the series format. Harrell’s latest work, The Ghost of Montpellier Meets the Samurai, explores an imaginary meeting between the founder of Butoh, a leader of French nouvelle danse and the namesake of La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. —Christopher Atamian

An Original Iconoclast: Simone Forti

Choreographer and improvisation artist Simone Forti has been immersed in the dance world for over 50 years. Her inquisitive spirit has placed her at the forefront of many evolutions in dance, from the early roots of improvisation with Anna Halprin to Robert Dunn’s famed composition workshops which birthed the Judson Dance Theater. Throughout her career Forti has pioneered the idea of thinking with the body, eschewing technique and instead relating words and pedestrian movement. Now 80 years old, this mother renegade offers her perspective on the movers and shakers she’s witnessed and her continuous creative hunger.

What is the role of renegades in our field?

Dance deals with physicality, which has a special place in this age of cyberspace. It provides a language for exploring questions, such as an evolving sense of personal identity.

Tell me about some renegades you’ve admired over the years.

Rather than teaching certain movements, Anna Halprin had us explore basic elements such as momentum and space, had us focus on sensing aspects of our bodies and observing movements in our daily world.

I also think of dancer Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage, poet Charles Olson, painter Josef Albers, to name a few, who worked in rich communication with each other, artists who looked to each other’s concerns, rather than to the concerns of the predecessors in their own fields.

But maybe there were some true renegades to start with. Marcel Duchamp, who presented a urinal as found artwork, turned basic questions upside-down by responding against the cultural moment. John Cage, who used chance as a tool for composition, was reaching for a Zen experience of pure sound. But once the new ideas, the new urgencies, have been stated, are the followers in those areas renegades?

Are you working on anything right now?

I sometimes joke that I’ve become Simone Forti’s secretary—my work has become part of our cultural heritage, and I have responsibilities towards that which don’t leave me much time to wonder about what I’d like to do. But I’ve recently done some performances with musician/composer Charlemagne Palestine. It was wonderful to again be moving fast, in circles, experiencing momentum and centrifugal forces.

—Madeline Schrock