What the Reactions to Debora Chase-Hicks’ Death Revealed About Divisions in the Dance World

On May 6, there was a tear in the universe and a void opened up when Debora Chase-Hicks died. For a large portion of the Black dance community, her name needs no qualifiers like “former star of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.”

A dance giant fell, and yet, if one paid close attention to news outlets and social media, taking notice of who acknowledged her loss, one could have easily drawn a line between the separate, parallel societies of the “Black dance community” and the larger body that is dance (the implied white being silent).

Indian freedom fighter Jawaharlal Nehru said, “History is almost always written by the victors and conquerors and gives their view.” And Philip Graham, the former publisher of The Washington Post, spoke only truth when he stated “journalism is the first rough draft of history.”

Today all aspects of history are being reevaluated through the lens of anti-racism and equity, and hopefully being crafted anew.

Yet the dance world still mirrors the inequity of the world at large where whiteness is the dominant culture. There are, however, a multiplicity of parallel societies (Black, Asian, Latinx, LGBTQ+, etc.) derived from marginalized communities. They are full and fecund, organically reflecting the value systems of their respective cultures. They crown their own leaders, heroes and martyrs, measured by their own barometer of greatness and excellence developed independently, but in full acknowledgment of the standards of the culture of whiteness.

Chase-Hicks was a game changer, an inspiration, an example for generations of dancers. Her sweet blend of technical prowess, artistry, integrity, grace and humility in classic roles in Talley Beatty’s Stack-Up, Ulysses Dove’s Episodes, George Faison’s Suite Otis, and Alvin Ailey’s For ‘Bird’ – With Love and Masekela Langage as well as the iconic solo Cry, garnered her the respect of her peers.

She was an anchor in a cohort of dancers who raised the standard of American modern dance. In the 1980s, she, along with fellow Philadelphians Gary DeLoach, Kevin Brown, Deborah Manning and David St. Charles, in addition to the likes of Marilyn Banks, Sarita Allen, Donna Wood, April Berry, Raquelle Chavis, Neisha Folkes, Sharrell Mesh, Dwight Rhoden and Desmond Richardson, were some of the final dancers handpicked by Mr. Ailey. It was this generation that set the model that has become the brand of excellence associated with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

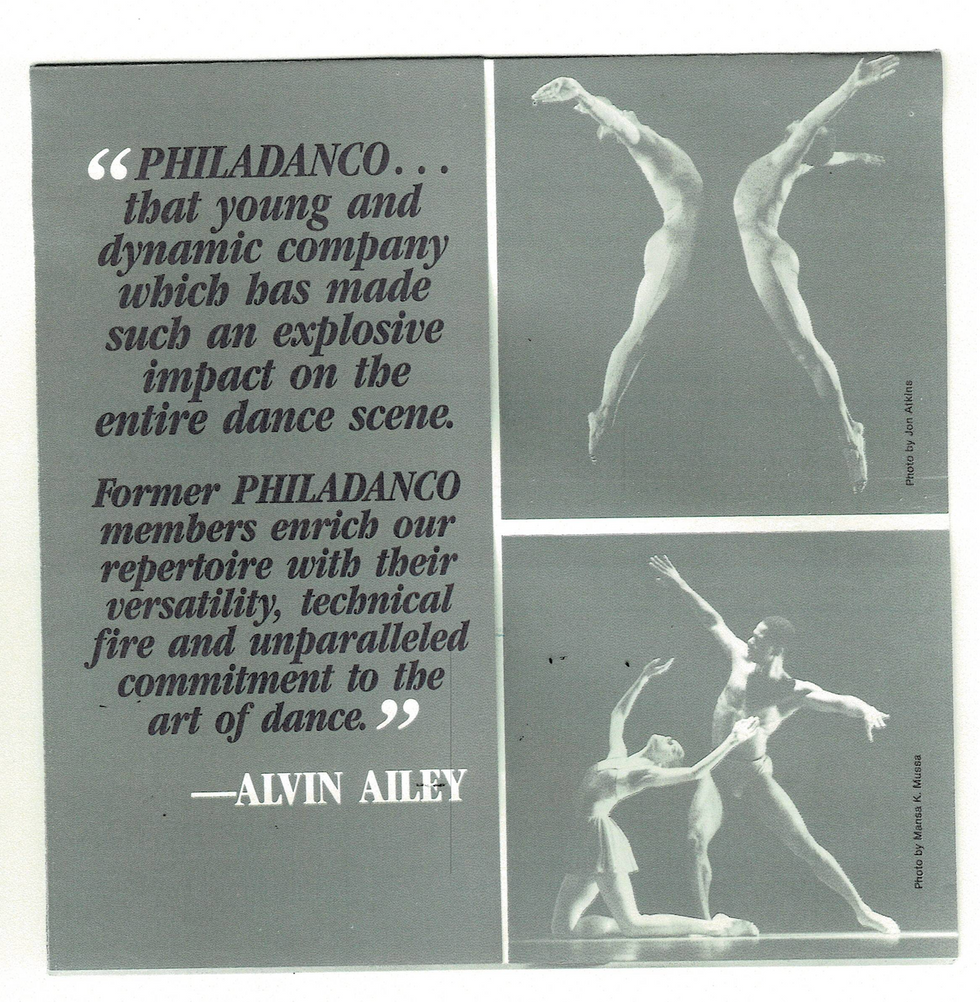

Debora Chase-Hicks was a blue blood of the Black dance world, a descendant from the lineage of Joan Myers Brown and her Philadelphia School of Dance Arts and Philadelphia Dance Company (Philadanco).

“Her movement quality,” muses Philadanco alum and recent Guggenheim fellow Tommie-Waheed Evans, “her captivating essence, her stage presence—she was as smooth as ice, so crystal-clear and so consistent. She had a deep understanding of her port de bras and also this deep understanding of what she was doing in space. She could get buck with it, or she could be soft and graceful. She was so diverse. And she was just gorgeous.”

“It was Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. It was not just ‘American Dance Company,’ ” says Raquelle Chavis, who was Chase-Hicks’ tour roommate and closest confidant. Reflecting on her friend, she says: “She made good choices. That acting, that dance-theater thing—she knew where she was in the space and how she’s going to utilize that space and bring you with her on that journey.”

We speak often of cultural appropriation, but less of cultural segregation. As the dominant culture, whiteness dictates the standard, assigns value and has power to ration and control access to opportunity. It has the authority to define how people of color are permitted to present themselves within their constructs, like the “urban” section in bookstores (where is the “suburban” section?) or the subdivision of Black, Asian or Latinx movies or shows (we don’t call them “white shows”). Lacking access and the ability to self-define, people of color empower themselves by creating their own spaces (BET Networks, Ebony, Essence, Netspan/Telemundo, La Opinión).

When we compare the legacies of George Balanchine and Alvin Ailey, two juggernauts in American dance history, the rolling imprint of systemic racism is quite evident. Both choreographers created dance companies and signature works, and they cultivated world-class dancers. Their divergent origin stories illustrate the role racial inequity played in the building of their careers. Balanchine came to the U.S. highly pedigreed via his work with the Ballets Russes, which led to his financial backing by elite arts society. Ailey climbed the ladder without much of a boost, and the tiny one he received in 1962 from the U.S. State Department came with huge caveats. The first was the insistence that the company be marketed as an “ethnic,” not a modern, company. The second was more insidious: The government threatened that if he “displayed” homosexual or effeminate behaviors on tour (in Asia and East and West Africa), it would bankrupt the company.

This same inequity can be read through the different ways dancers are presented with opportunities post-retirement. White dancers of pedigree are often headhunted for positions in leadership, sought out by legacy organizations to partner or collaborate, their projects supported by funders, presenters and the press. The extension of access and opportunities is an act of preserving and carrying on these ordained artistic bloodlines. The system determines what is “important” enough to preserve (this bias is markedly evident in the world of archiving).

The same cannot be said of the Black modern dancers who carry Ailey’s legacy, and for that matter the Dance Theatre of Harlem alumni who danced under Arthur Mitchell. Artistic directorships are not offered, full-time faculty positions can be hard to come by. When they do capture roles in leadership, it is often after paying a high tariff of work in the trenches of the dance field or academia, which often renders them overqualified while paid a fraction of the salary and, often, standing on a glass cliff. Meanwhile white dancers from prestigious ballet companies seemingly waltz into leadership straight from the stage; some are given multiple times to fail in such positions and are paid handsomely to do so.

In our racialized society, it could be argued that Black excellence is valued equally to white adequacy. Standards and criteria apply in a more fixed manner for people of color (specifically Black people) than for their white counterparts. One could argue that some of this is due to the hierarchy of dance, with ballet positioned at the apex. However, white modern and postmodern dancers also benefit from their proximity to what is deemed white genius.

And what of the genius in Blackness? The ingenuity of thwarting a system built to deny you can be categorized as little else. Philadelphia School of Dance Arts and Philadanco have consistently trained and prepared generations of dancers for professional careers in a variety of dance genres. Joan Myers Brown built a metaphoric underground railroad to possibility, not only for Black artists but for anyone who crossed the threshold of her organization. (Note the organic diversity and inclusion, no initiative required.) “We counted the other day. There were 22 dancers who went to Ailey from ‘Danco,” says Myers Brown. It makes you wonder if there’s something in that Philly “wooter.”

For years there was an urban legend that Myers Brown was resentful that her dancers left for Ailey. However, the opposite is true: The two directors worked together to create a pipeline of opportunity. Myers Brown remembers getting a call from Alvin Ailey. “He said, ‘I have two girls here from Philly.” It was Chase-Hicks and Deborah Manning, and he was asking which he should take. “‘I know you don’t want me to have both,'” Myers Brown recalls him saying. “I said, ‘You got to take both.’ That’s when they got to be ‘the two Debbies from Philly.'”

Which brings us back to Chase-Hicks. When asked where she acquired her formidable and versatile technique, Chase-Hicks proudly proclaimed “Joan Myers Brown was my ballet teacher,” Raquelle Chavis recalls. Myers Brown was classically trained by Sydney King and Marion Cuyjet; both women were known for exposing their students to a myriad of techniques and teachers. Following her mentor’s blueprint, Myers Brown amassed a cadre of master teachers for her students: Delores Browne, Marion Cuyjet, John Hines, Pat Thomas, Fred Benjamin, along with white teachers like William Dollar and Karel Shook. Denise Jefferson, while the director of The Ailey School, traveled from New York City weekly to teach at the Philadelphia School of Dance Arts, as did Milton Myers.

Courtesy Philadanco

“It was a time before Horton,” says Myers Brown. “I studied with Dunham, so I started them with ballet, jazz and Dunham. The kids talk about how it gave them that strength and perseverance and determination.” Her company dancers were built by choreographers like Fred Benjamin, Talley Beatty, Billy Wilson and Eugene Sagan. The result was a dancer who could do everything and anything.

“There was never a hierarchical understanding of dance. Ballet, Graham, Dunham, all the things were always treated with the same amount of respect,” recalls Robert Garland, director of the school at Dance Theatre of Harlem and resident choreographer, and a Philadanco alum. “The first time I saw 32 fouettés was Deborah Manning and Debora Chase-Hicks turning to a disco song called ‘Ring My Bell.’ I’ll never forget it,” he says with a chuckle. Everywhere the students looked they saw their likenesses in Black excellence.

This flattening of the hierarchy of genre is a crucial component to the “decolonization of ballet” the dance world is calling for in 2021. It has been a practice in the Black community for decades. It was the thinking that allowed for classically trained Black pioneers like Myers Brown, Katherine Dunham, Louis Johnson, Talley Beatty, John Hines, Delores Browne, Janet Collins and Billy Wilson to seamlessly move through the genres when opportunities opened up. Wilson started his professional career in musical theater and later transitioned to a soloist position as a founding member of the Dutch National Ballet (when usually it works the other way around). Ironically, a byproduct of the restrictions of systemic racism is versatility: Not only does it make Black folks twice as good but in twice the areas.

A great number of these Black dance educators had their dance career dreams deferred or truncated due not to a lack of talent but to segregation. They poured that desire, passion into their students. They held high expectations, and did not mince words; they prepared their dancers for the real world onstage and off.

All artists are encouraged to have “something to fall back on,” but for dancers of color for whom the options are slimmer, it is seen as even more crucial. Myers Brown was adamant about students having a skill that could pay their bills. Chase-Hicks had been a bank teller while she danced with Philadanco, and when she retired from Ailey she enrolled in stenography school. When she returned to Philadanco as rehearsal director, her stenography skills served her well, allowing her to type notes while never taking her eye off the dancers. She missed nothing.

She did not consider herself to be a rehearsal director. She was once quoted as saying: “Rehearsal director? I’m a coach. The ultimate goal, of course, is to keep the ballet intact. But, I love to work one-on-one. Coaching is nurturing—teaching, actually—and I love that so much.” In a competitive field where younger dancers can be seen as a threat to seasoned veterans, and a rite of passage in old-school company culture is for newbies to “figure it out on their own,” Chase-Hicks did not subscribe to this mentality or behavior. “In the two years I got to share the stage with her, she would give me little tips and hints: how to secure a headdress or, in Blues Suite, how to hold the pink fan at the end,” says former Ailey dancer Danni Gee, one of the 22 who came through Philadanco. “One beautiful moment was when I was doing her track in House of the Rising Sun, she showed me this is how you bring the stool out in the dark, how to place it and get the scarf off on the chair, quickly.”

“She was your biggest cheerleader,” adds Chavis. “She never wanted to see anyone be defeated or fail. She was always pushing you to be the best that you can be. And if she saw something that might help you, it could be just a little thing, like what your pinky finger’s doing…”

Her process of welcoming a new dancer into Philadanco was a one-on-one rehearsal on her own time. “She came up to me and said, ‘I want to rehearse with you on our own.’ She went through that entire track with me, she told me what to expect in rehearsal later that night. She would get inside the work as if she were dancing it,” says Tommie-Waheed Evans. “She would talk to you about the character work that you were building and the nuances that you were stumbling on. She made us all artists, not just simply dancers.” In a way, she became a conductor on Myers Brown’s underground railroad, developing in them the skills they would need on their journey.

But it was her artistic eye and attention to detail that truly made her a great. “Debora Chase-Hicks was a master class,” is what choreographer Camille A. Brown says wistfully. Brown recalls working beside her while setting work on Philadanco. She was awed by Chase-Hicks’ ability to see, hear and reinforce her choreography’s intention and details as rehearsal director. When Brown returned after a hiatus, she recalls, “The piece was exactly how I left it in the best of ways. I didn’t have to reinforce all the stuff that I had said before I left. Walking in and seeing it felt like, ‘Oh, she cared for this piece while I was gone.’ And that’s so powerful because she provided a space for you to move to the next level of whatever you want to do. She held it so carefully that I didn’t have to think of all the extra stuff. I just had to focus on challenging myself and challenging the work.”

The institutional knowledge that Chase-Hicks literally embodied and the level of integrity in which she worked to preserve the intention of the choreographer’s work would have been lauded had she been a stager for a choreographic trust. Most choreographic works by Black masters are not held in trust but by family members. This is because most Black dance companies were founded out of passion and necessity—creating a space to dance and tell our stories. Often the nuts and bolts of business were cultivated on a need-to-know basis. Most organizations had to stay in the present, working to survive, leaving little bandwidth to think about the future (archiving, trusts, etc.). Historically, the contributions of artists of color have been sorely under-documented and when these incredible artists, with invaluable experiences and knowledge, die, the institutional knowledge dies with them.

If “journalism is the first rough draft of history,” and if we recognize history as a pillar in the process of creating equity and leveling the field, then it is incumbent on journalists and the media to use their pens and platforms to assist in correcting the narrative.