As He Retires from The Royal Ballet, Edward Watson Leaves a Lasting Legacy in His Wake

There are two sides to Edward Watson, the mold-breaking principal who is bidding farewell to The Royal Ballet this fall. Wayne McGregor and Christopher Wheeldon, who have created landmark roles for him over the past two decades, both call him “shy,” and the 45-year-old agrees, describing himself bashfully as “quite tense about my abilities.”

Yet, as anyone who has seen Watson perform can attest, he has also been one of the most consistently fearless performers to grace the ballet stage—from his bendy and mind-bending turns in McGregor’s repertoire to the depths of suffering he lent to Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s Mayerling and Arthur Pita’s The Metamorphosis. Fittingly, he will retire with an evening-length creation by McGregor, The Dante Project.

“Everything I’ve done, I’ve questioned and felt that it’s all going to be a disaster, but somehow I’m on there doing it,” Watson says. “I found a way of being able to decide ‘I’m deciding to be good tonight. I won’t let that doubt override everything.’ “

Along the way, his instinct and wiry intensity have broken new ground for male dancers. Gone are the days when—as a young, gangly redhead whose strengths didn’t lie in bravura male technique—Watson wasn’t deemed “English prince” material. While he joined The Royal straight after graduating from The Royal Ballet School, in 1994, his promotion to principal only came in 2005. In his entire career, he never danced the lead roles in The Sleeping Beauty or The Nutcracker. With a laugh, Wheeldon calls him “anti-cute.”

What Watson did instead was carve a new space in British ballet, with the help of a generation of choreographers and stage partners. When McGregor was first invited to work at the Royal Opera House, as part of an experimental program in a small studio in 1999, Watson showed up at the first rehearsal, in his free time. “He was this alien presence in this tiny room,” McGregor remembers.

As McGregor’s choreographic career took off, Watson went on to become one of his most rewarding artistic partners. Watson calls 2006’s Chroma “a huge bomb, it was so exciting.” A dozen ballets ensued, with his role as the traumatized war veteran Septimus in Woolf Works an astounding high point. “He has all that somatic intelligence, layers of it. He’s never been bound by his classical technique,” McGregor says.

Wheeldon, who overlapped with Watson at The Royal Ballet School for a few years, also turned to him for creations early on, starting with Tryst in 2002. Watson was the inspiration behind the roles of Lewis Carroll/The White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the jealous Leontes in The Winter’s Tale. “I made The Winter’s Tale for Ed,” Wheeldon says. “His interpretation of what I give him is almost always so much more interesting than what I gave initially. He’s so distinct, so unusual.”

McGregor and Wheeldon see Watson as an astute collaborator in the studio. “He’s really discerning. You can always tell with Ed when he politely doesn’t like something,” Wheeldon says. “He’s brutally honest, and he has a wicked sense of humor,” McGregor adds.

Has either of them ever asked Watson to do something he found impossible? “No, that’s not my way,” Watson says. “My way would be going ‘Let me have a try, think about how I could do that.’ “

“He’s made a massive contribution to The Royal Ballet,” says the company’s director, Kevin O’Hare. “He’s right up there in the history books of the company as one of the great dramatic artists, with an extraordinary physicality.”

His impact behind the scenes in London has been no less significant. Joseph Sissens, who joined The Royal Ballet in 2016 and is now a first artist, calls Watson “an enormous queer role model”: “Ballet tends to have a filtered look on sexuality, and he changed that for a lot of us.”

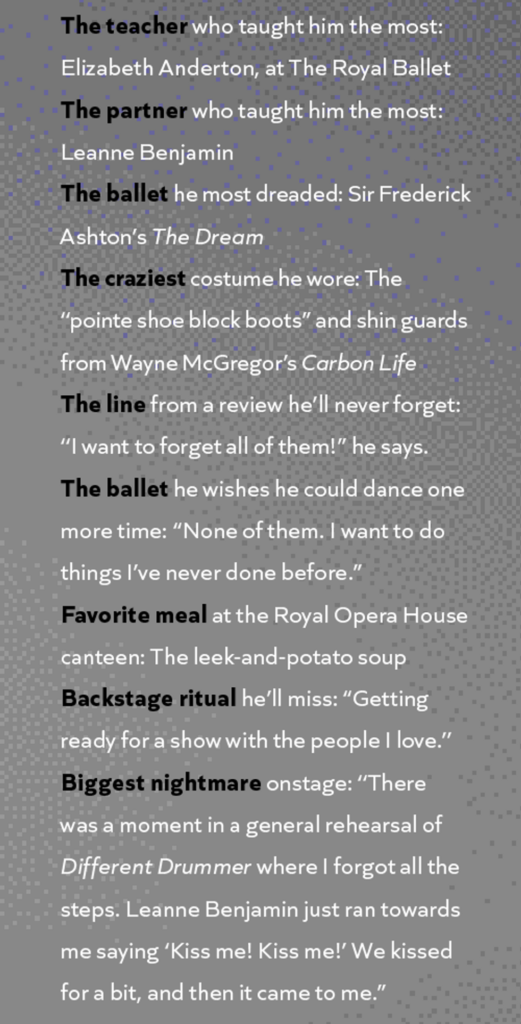

Over the years, successive directors made space for Watson’s individuality to mature in historical repertoire, too. Watson credits former principal Leanne Benjamin, known as an outstanding dramatic dancer, with helping to introduce him to works like Giselle, Firebird and Sir Frederick Ashton’s The Dream. “The two of them were so singular in their approach to movement—neither of them particularly Royal Ballet, even though they ended up almost defining a new generation of The Royal Ballet,” Wheeldon says of Benjamin and Watson.

Mara Galeazzi was another key partner in ballets, including Mayerling. “Seeing Leanne and Mara’s bravery, their confidence—we kind of rubbed off on each other,” Watson says. The two ballerinas’ retirements the same year, in 2013, were tough. “I didn’t have my backup team anymore. Suddenly I felt a little like I was starting again.”

Watson kept venturing out of his comfort zone, however, with experimental projects, like his 2015 collaboration with Wendy Whelan, Whelan/Watson: Other Stories. In 2011, after just one coffee date with the choreographer Arthur Pita, he agreed to help him bring Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis to life, and convinced Deborah Bull, who was running the Royal Opera House’s second stage, the Linbury, to produce it there. Onstage, Watson slowly morphed into a goo-covered, bug-like creature, with eye-popping articulation—down to individual toes. As with everything else he’s done, the process was all-consuming, he says. “If I’m working on a role or if I have a performance that evening, it’s all I think about. I don’t sleep. My brain is constantly on it.”

Watson believes he achieved a peak from about age 36 to 41: “I felt like technically, emotionally and experience-wise, it all came together.” That came to a halt when his plantar plate ruptured, in 2017. Two setbacks followed when he tried to get back to the stage (a sprained ankle, and a broken bone in his foot). “You realize the amazing things you’ve been asking your body to do for so many years.”

While his farewell was delayed by his injuries and the pandemic, retiring with a major new work like The Dante Project—in which he will take on a role based on Dante himself—is a fitting tribute to his many years as a creative force. “It feels right, working with Wayne for so long and finishing on a new ballet,” Watson says. That context will imbue the work, as McGregor sees it. “That whole Dante story is around a massive moment of change, it’s very personal—me in my 50s, Ed in his moment of transition.”

That transition is already well underway: Last year, Watson was appointed a full-time répétiteur with The Royal Ballet, after “helping out here and there” for a few years. “I like being surprised by what’s in front of me in the moment, making people feel brave enough to try something,” Watson says of his new role. Dancers are clamoring to work with him, O’Hare notes, with Sissens adding that Watson brings “an element of happiness” to the studio: “He wants us to enjoy the moment.”

Still, McGregor is convinced we will see Watson onstage again: “There’s no way he is stopping working physically and creatively.”

“I’m not saying I will never be seduced by an idea or a project,” is Watson’s answer. But he is ready to say goodbye to life as a Royal Ballet principal. “It will be very different—but what a thing to have done with the first half of my life.”