Introducing Our 2020 “25 to Watch”

Breakout stars, paradigm shifters, game changers. Our annual list of the dancers, choreographers and companies that are on the verge of skyrocketing has a knack for illuminating where the dance world is headed. Here they are: the 25 up-and-coming artists we believe are ready to take our field by storm.

Gabrielle Hamilton

It’s rare that your first job out of college gets you noticed, much less wins you both a Chita Rivera Award and a Bessie Award. But that’s what happened when Gabrielle Hamilton was hired to dance in Daniel Fish’s edgy production of Oklahoma! in Brooklyn in 2018. It ended up on Broadway, where John Heginbotham’s punchy, barefoot, 13-minute solo—a complete rethinking of the show’s famous dream ballet, originally choreographed by Agnes de Mille—showcases Hamilton’s fluid, tensile line and the explosive intensity she brings to every moment.

The 24-year-old Harlem native began at 3, training in a wide range of forms—gymnastics, African dance, ballet and more—and had envisioned dancing on Broadway as the ultimate goal of a long career slog. Instead, it’s the beginning, a unique launching pad that can send her in any number of directions. She doesn’t mind. “I’ve always wanted to dabble in different things,” she says. “I never wanted to be restricted to only one.” So she’s looking ahead to more Broadway, of course, and whatever follows. “I want to see what else is for me as a dancer and as an artist,” she says. And so do we. —Sylviane Gold

Steve Smith, Courtesy LED

LED

LED is as much about music as it is about dance. The two are developed simultaneously in a seamless process that choreographer Lauren Edson describes as “completely fluid,” telling visual and kinetic stories set to music that is often played live by the troupe’s in-house band. Founded in 2015 by the Boise-based Edson and her husband, composer Andrew Stensaas, LED and its project-based model are taking off, garnering support from the local community that grew to love dance during the Trey McIntyre Project years.

Edson’s brand of theatricality borders on whimsy with a whiff of narrative. She has a way of fusing slippery pedestrian movement with virtuosic eye candy that invites the audience into another world, mining the dancers’ nuanced idiosyncrasies to imbue the work with texture and charm. The result is dances that are fun, sexy and downright cinematic. With the troupe’s penchant for dance filmmaking, look for LED to expand its influence beyond Idaho. —Nancy Wozny

Maya Taylor

From sensual, free-flowing swirls to sharp walking formations, commercial choreographer Maya Taylor’s movement layers styles with a subtle maturity. She was nominated for a 2019 MTV Video Music Award for Best Choreography for Solange Knowles’ edgy “Almeda” video and has collaborated with Solange on four others since 2016. Taylor’s chameleon-like approach has also led to commissions from St. Vincent, SZA and Arcade Fire’s Régine Chassagne.

A former Elisa Monte dancer and an Ailey School alumna, Taylor now bounces from the set of TNT’s “Claws” to touring with Solange as a concert movement director. Even as her commercial opportunities have increased—including recently choreographing her first feature film, Netflix’s Dirt—contemporary commissions have kept Taylor’s concert dance chops sharp. Those roots bring a refreshingly nuanced depth and intrigue to her work that is unusual for the scene. —Jen Peters

A Little Old, A Little New at Jacob’s Pillow Christopher Duggan, Courtesy Hickey

Luke Hickey

It’s hard to sit still watching Luke Hickey perform—and he never seems to stop moving either. In his solo “What’s New,” he’s rarely in the same place for more than a few seconds, crisscrossing the stage with impeccable footwork and inventive phrasing. A swinging step borrowed from Bill “Bojangles” Robinson morphs seamlessly into a heel-heavy triplet rhythm. A simple shuffle sequence in place suddenly sends him skittering across the floor with impressive clarity and agility. With each new step, he finds ways to explore and expand the rhythm, like a musical Russian doll.

The piece is part of A Little Old, A Little New, Hickey’s first full-length endeavor as a choreographer, which debuted at New York City’s Birdland Jazz Club before its Jacob’s Pillow premiere last summer. Yet he’s anything but new to the stage: An alumnus of the North Carolina Youth Tap Ensemble and the touring show Tap Kids, the Brooklyn-based hoofer and filmmaker has performed with many of the field’s leading dancemakers. In the past year alone, he appeared with Michelle Dorrance at New York City Center, Caleb Teicher at The New Victory Theater and Ayodele Casel at The Joyce Theater. At 23, the charming young performer isn’t just holding his own among the Big Apple’s top tap talent—he’s quickly joining their ranks. —Ryan P. Casey

Annie Morgan

Stage presence seems to be in Annie Morgan’s DNA. When she performs, it washes over the audience, drawing them ever closer. Even the wonkiest of moves are infused with her inherent grace and fluidity. In David Shimotakahara’s Sud Buster’s Dream, she twists and contorts her body like Houdini struggling to escape a straight jacket. In Brian Brooks’ Unwritten, she dips, sways and turns through intricate patterns as if immune to gravity’s power.

“My strengths are in the emotional side of performance,” says the 24-year-old. Trained at the Alabama School of Fine Arts and Pittsburgh’s Point Park University, Morgan joined Cleveland’s GroundWorks DanceTheater right out of college in 2018. Shimotakahara, GroundWorks’ artistic director, says, “She takes in information and brings it together with what’s inside in ways that go someplace unexpected.” That skill has already made her a favorite with visiting choreographers and audiences alike.

—Steve Sucato

prettygirl264264 Fred Attenborough, Courtesy Yergens

Ashley R.T. Yergens

Go-go dancing may only be a side gig for Ashley R.T. Yergens. But it has taught him an important lesson: Audiences pay hard-earned money for the performances—whether in tips at clubs or for tickets to downtown dance venues. He’s applied this transactional mind-set to his own concert dance work, aiming (successfully) to appeal to more than just dance insiders.

In his prettygirl264264, the 27-year-old throws himself a living funeral, responding to the ways in which trans people are often disrespected in death as well as in life. But the dance-theater work is anything but dark and pedantic: Yergens incorporates mountains of party balloons, a Celine Dion singalong and scenes from Becoming Chaz, the 2011 documentary about Cher and Sonny Bono’s son, who is also trans. It’s all part of Yergen’s desire to “meld aesthetics that don’t belong together” and to show how, actually, they aren’t so opposed.

Next up, Yergens is developing a piece called C*NT C*NTEMPORARY as part of a two-year residency at New York Live Arts. Long-term, Yergens wants to forge a legacy of trans artists in dance—without always having to make work that’s about being trans. —Lauren Wingenroth

Abdiel Figueroa Reyes

There’s a subtle playfulness to Abdiel Figueroa Reyes’ gangly limbs, his ability to gain quick control like a game of catch-and-release. Keen partnering skills, a silky-smooth style and a compelling balance between youth and maturity have quickly propelled him into a career with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

Reyes started dancing at age 4 in Puerto Rico, where his mom and aunt owned a studio. The family moved to Las Vegas when he was 13 so he and his brother could pursue dance seriously. A summer at Axis Connect introduced Reyes to Alexandra Wells, who convinced him to enroll in the inaugural class of HS Pro, Hubbard Street’s professional training program. A few weeks later, he was onstage with the company, performing in Peter Chu’s Space, In Perspective. After an apprenticeship in the 2018–19 season, he made his debut as a member of the main company this November, entering just as three other men departed—fortuitous timing that might land him center stage even sooner than expected.

—Lauren Warnecke

Out of Bounds Andrew Mandinach, Courtesy Carlon

Jay Carlon

If you want to be utterly transported, look to choreographer Jay Carlon. His work is so theatrical, so absorbing that you forget where you are—which is often the most mundane of spaces. He transforms a dark parking lot, a beach, a public park or a sand-filled backyard into another world populated by fully realized characters.

He subverts the audience’s expectations and point of view, pulling them deeply into his vision: a 1950s ballroom; refugees wrapped in golden “blankets” stepping onto a beach; a wrestling gym; a funeral home where a traditional Filipino bench dance transforms into a coffin and resurrection. His movement is often highly physical, relentless and acrobatic—you can see the ferocity and athleticism he demands of his emotionally committed dancers. The Los Angeles–based, Filipino-American 12th child of a “migrant working family,” Carlon uses his choreography to touch on race, identity, colonialism and gender—as well as love, family and belonging. —Abigail Rasminsky

Hannah Garner

It isn’t easy to make an audience feel like they’re a character in your show. But in Hannah Garner’s RED, the audience plays Little Red Riding Hood. That is, when Red isn’t played by one of the four performers, who switch characters—one moment the wolf, the next the grandmother—seamlessly.

RED

was Garner’s first work that heavily relied on audience participation, but you wouldn’t have guessed. Each choice felt necessary, rather than just an excuse to break the fourth wall. Moments of humor added dimension, not distraction. (In one of these, the audience learns a melody from the performers, only to later realize they’re singing ABBA’s “Dancing Queen.”)

Garner, who founded her New York City–based 2nd Best Dance Company in 2016 with three friends from SUNY Purchase, creates work that “stands at the border of humor and tragedy,” she says, and tackles topics like death and queer identity through rigorous, inventive movement and wit. A year as artists-in-residence at Brooklyn’s Triskelion Arts and a performance with Gibney’s dance-mobile series have recently boosted the company’s New York profile. But with music videos for artists like Stolen Jars on the docket, Garner’s work will soon be seen by a more global audience. —Lauren Wingenroth

Obsidian Tear Tristram Kenton, Courtesy ROH

Joseph Sissens

Joseph Sissens’ long, long legs are the first thing you notice. The 22-year-old from Cambridge, England, is a dancer of lean elegance, expansive lines and beautiful footwork. Choreographers at The Royal Ballet make a beeline for him. Wayne McGregor—a man with an astute eye for talented dancers in the corps—cast him in Obsidian Tear and Yugen. Twyla Tharp chose him for The Illustrated ‘Farewell’. And the first artist’s appearance in new work by contemporary choreographer Alexander Whitley and a slinking, grooving solo, jojo, by up-and-comer Charlotte Edmonds suggests a dancer with a curious mind, as well as a protean facility for whatever physical demands are thrown his way.

Outside of The Royal, Sissens stood out among a superlative lineup in the Merce Cunningham celebration Night of 100 Solos, where he gave Cunningham’s exacting geometry a gossamer edge. But he’s flexing his elongated muscles in some classics, too, making his debut as Lensky in John Cranko’s Onegin this year. —Lyndsey Winship

Dean Paul, Courtesy Ensemble Español

Luis Beltran

Luis Beltran has an intrepid mix of charisma, confidence and sex appeal. He seduces audiences with a fair share of tantalizing machismo, but it’s not boorish, and it’s balanced by a blithe and jaunty stage presence in Ensemble Español Spanish Dance Theater’s folk dance repertoire. Beltran manages to find the nuances in each Spanish style—folkloric, flamenco, classical and contemporary—but shines most in the company’s big, bold, unabashed and spectacularly over-the-top group works.

The native Ecuadorian started dancing with an outreach program hosted by Chicago’s Ensemble Español at age 7, then rose through the ranks to join the company in his late teens. Now 25, he’s on track to rise to the top of a company whose Spanish dancers are among the best in the world.

—Lauren Warnecke

Pitkin Grove Maria Baranova, Courtesy Edwards

Joyce Edwards

In Beth Gill’s Pitkin Grove, Joyce Edwards shone. Wearing glowing gold makeup and lace-up high-top boxing shoes, she glided around the four-sided stage in a solo made on her. Often with fists raised, she deliberately stepped and sometimes stomped in a riveting dance of composed combat with an invisible enemy. Her ease, suppleness and confidence captivated—and she was still an undergraduate student at SUNY Brockport.

Edwards speaks about dance in the same precise and intentional way she moves. She says, “I don’t think I could arrive at a place of performance without failure in the studio, without time and space to try on a bunch of different things. And I feel like I can’t, as a black, queer woman, always do that safely. So, I turn to dance for love, for clarity, for a lot of things that I don’t necessarily have access to always.” During her undergraduate career she performed with Ronald K. Brown/Evidence at Bard’s SummerScape festival and worked with Netta Yerushalmy. When she returned to the U.S. this winter after a semester abroad in Spain, a company position with Evidence was waiting for her.

—Caroline Shadle

Zenon Zubyk

With lanky limbs and wild red hair, Zenon Zubyk revels in a uniquely awkward virtuosity. During an unforgettable solo in To this day—a work Emily Molnar crafted with Ballet BC’s brilliant dancers-as-collaborators—the 22-year-old masterfully navigates between a comedic courting ritual and mesmerizing showmanship. In an insect-like mating dance set to Jimi Hendrix, he turns himself inside out for an unamused female observer, somehow meshing gangliness with serious cool.

The dancer is a recent alumnus of the Arts Umbrella Graduate Program, and after one year at Ballet BC’s emerging artist rank, Zubyk was promoted to full company artist for the 2019–20 season. Although he has plenty of technical tricks up his sleeve—he was a comp kid prodigy who won the 2013 New York Teen Male Best Dancer title at The Dance Awards—he investigates movement with extreme care for detail. Molnar will leave her artistic director post at the end of this season, but Zubyk’s idiosyncratic performances guarantee he’ll continue to be a standout. —Jen Peters

Julie Crothers

With a penchant for both the heartfelt and the hilarious, Julie Crothers is taking the San Francisco Bay Area by storm with her autobiographical solos. “I like to make people laugh and then cry,” she says. “I want to encourage audiences to look inward and feel more connected.” Whether she’s regaling them with the romantic escapades of her beloved grandmother or winding her way through a tiny glass menagerie—her comfort items from childhood—Crothers has an uncanny knack for appealing to her audience’s sense of humor, compassion and curiosity.

As a congenital amputee, Crothers, 27, began using a prosthetic arm at just 5 months old. After an eye-opening visit to Bates Dance Festival during college, she stopped using the prosthetic altogether (except occasionally as a prop in her work). Following a three-year stint with AXIS Dance Company, Crothers set out on her own in 2017. “I have a little sadness when I think about my former self who was so terrified of sticking out,” she says. “I want to encourage audiences to look at the things that make them different and see how that’s something you can own, claim, declare and utilize for good.”

—Rachel Caldwell

Lizzie Tripp

Contemporary movement flows from Lizzie Tripp like a Shakespeare sonnet. In the opening solo of Enrico Morelli’s The Noise of Whispers in 2017, she bewitched audiences with supple airiness, nuanced complexity and heartfelt intensity. Now in her fourth season with Milwaukee Ballet, the 23-year-old has not only performed featured roles in several contemporary ballets, but has also appeared as the Snow Queen in The Nutcracker and the Enchantress in Michael Pink’s Beauty and The Beast—a role she originated in 2018.

Tripp trained at the company’s official school and started her career at its second company, growing up and into her artistic identity within the organization. Dancing in Pink’s Peter Pan this spring as a company member, she’ll come full circle: She performed in the premiere as a child. —Steve Sucato

Loreto Jamlig, Courtesy Desardouin

Tatiana Desardouin

A graceful powerhouse, both onstage and off-, Tatiana Desardouin is on a mission. She moved to New York City in 2016 to pursue her dream of creating a dance company in the birthplace of hip hop. The resulting all-female Passion Fruit Dance Company embodies the complexities of street and club dance, using vocabulary that stems from both hip hop and house. Desardouin emphasizes these styles’ roots in black culture and is dedicated to exploring them as cultural forms, approaching her work as a call to action. “You cannot be about this culture, about this movement, and not support the struggle of my people,” she says.

With subtle, precise torso isolations layered over quick-fire footwork, polyrhythms and counterpoint predominate. Desardouin’s eye for transitions and her ability to shift effortlessly from powerful and dynamic to soft and smooth result in stylistically multifaceted pieces. Within, she creates tensions that encourage audiences to ask questions surrounding the racial and identity politics of these styles: Who created them? Who does these dances, and where? Who consumes them, and why? Challenging her dancers as much as her audience, Desardouin leads by example. “Create the world you want to live in,” she says. “There’s no other way.” —Ephrat Asherie

The Sleeping Beauty Rich Sofranko, Courtesy PBT

Tommie Kesten

Tommie Kesten is not one to go unnoticed. The 19-year-old Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre corps member couples joie de vivre with mature movement choices. A Pittsburgh native, she joined the company in 2018 and has already garnered featured roles.

As the “tall girl” in Balanchine’s “Rubies,” Kesten, who at 5′ 4″ is not the traditional height for the role, filled the stage, her beautiful extension paired with bright, darting eyes and a brilliant smile. In The Sleeping Beauty, she took a thoughtful approach to her pacing and characterization in the Bluebird pas de deux. The athletic dancer’s unquenchable drive has her on a fast track to company stardom.

—Steve Sucato

The Sleeping Beauty Gene Schiavone, Courtesy ABT

Zimmi Coker

She has only been a fully fledged member of the corps since June 2018, but already American Ballet Theatre’s Zimmi Coker is popping up everywhere. She tore into Michelle Dorrance’s highly syncopated, tap-infused movement in Dream within a Dream (deferred). She scampered about the stage with feverish intensity as the young Adele in Cathy Marston’s Jane Eyre. And she exuded confidence and joy as one of the two sneaker-clad “stompers” that open and close Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room.

What you notice about Coker is the clarity and intention with which she dances. Whatever she’s doing, from the smallest character role to an ensemble part, she does full-out. “I’ve learned the importance of expressing detail with each movement,” she says. “And I try to be mentally fully present for any rehearsal or performance.” It shows. —Marina Harss

Principia Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Mira Nadon

Eyes find Mira Nadon quickly onstage, even when she’s stationed in the tall-girl back row of the corps. The 19-year-old New York City Ballet dancer has an open, large-featured face that’s strikingly readable from the audience. And her dancing is every bit as legible: expressive but never sentimental, authoritative but never overbearing. She says what she wants to say in simple sentences, free of italicization.

Nadon can also parse multiple choreographic languages. As the Fairy of Courage in The Sleeping Beauty, she delivers Petipa with nary an accent. Choreographer Pam Tanowitz’s sophisticated phrases are the dance equivalent of tongue twisters, but last spring, in Tanowitz’s Bartók Ballet, Nadon spoke them fluently. And in her mother tongue, Balanchine, she’s unstoppable. Her debut as the siren soloist in “Rubies” last fall had polish, panache, power—a performance in full voice. You won’t need to seek out her face in the corps crowd for long. —Margaret Fuhrer

Ounce of Faith Paul Kolnik, Courtesy AAADT

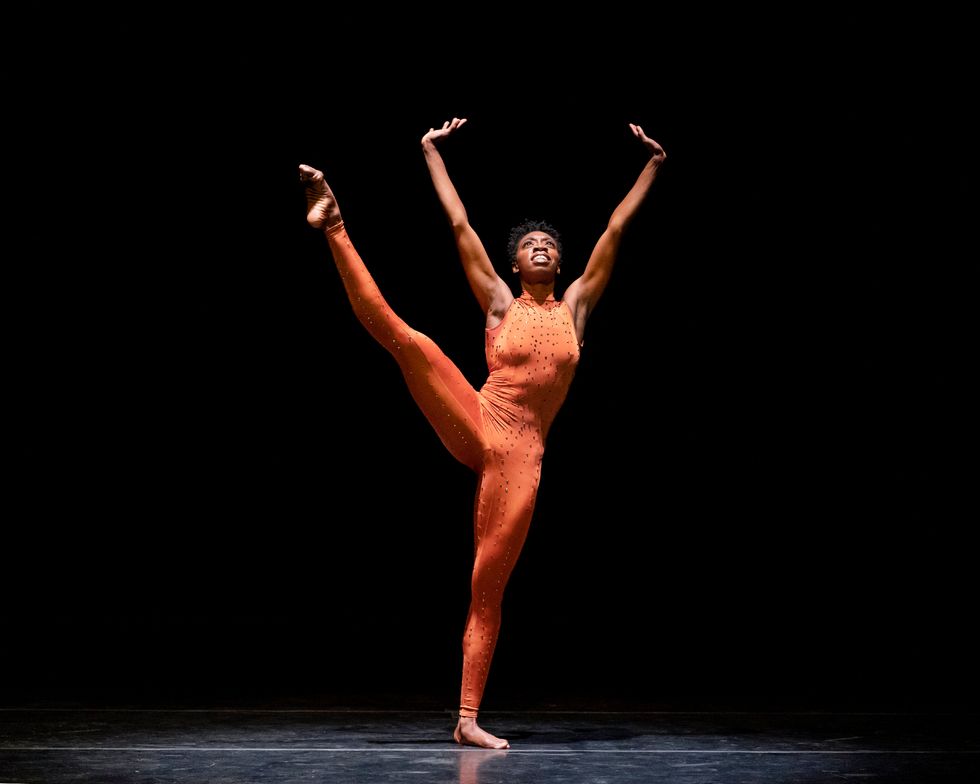

Khalia Campbell

Emotions flood through Khalia Campbell’s every move. As “the umbrella woman” in Ailey’s Revelations, her torso and arms ripple with joy. As a soloist in Darrell Grand Moultrie’s Ounce of Faith, she turns heads with dancing that’s smooth and silky, yet sharp and purposeful.

Campbell first stood out as a long-legged gazelle on the Ailey II stage. But since joining the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2018, she’s become even more commanding. Proud of her role in the company’s legacy, the Bronx native holds nothing back onstage, generously giving her all to the work—not just physically, but spiritually. —Charmaine Warren

Body, Movement, Language at the Google Creative Lab Courtesy Man

Maya Man

Maya Man works at the intersection of movement and machines. As a technologist at the Google Creative Lab, she recently collaborated with Bill T. Jones to complement his improvisatory practice with state-of-the-art machine learning, exploring how the new technology can augment artistic expression. The project lives at BillTJonesAI.com, where anyone can try out the resulting web experiments and watch the film documenting the process.

Man considers herself an artist, dancer and technologist hybrid, and across those roles one can glimpse the dancemaking of the future: where bodies are augmented digitally, performances are enjoyed as much online as off- and the choreographer also codes. Man isn’t waiting for that future to arrive, though. An exceptional hip-hop dancer, she regularly shares videos of her dancing (as well as her technological pursuits) with her growing Instagram audience. She’s also been a persuasive presence on the public speaking circuit, featured recently in New York Live Arts’ Live Ideas festival. Her genre-warping career defies conventional expectations of what it means to be a successful dance artist. —Sydney Skybetter

Four Quartets Maria Baranova, Courtesy Chan

Kara Chan

Kara Chan has emerged in the latest iteration of Twyla Tharp’s troupe as a petite yet powerful force. She recently tackled Tharp’s own role in a reconstruction of Eight Jelly Rolls and nailed the quintessentially Tharpian “drunk” solo, swinging and loping across the stage in a full-bodied, loosey-goosey romp. In The Fugue, Chan masterfully flew through the complex direction changes and footwork. No matter the choreographic undertaking, she dances with what has become a characteristic warmth.

Tharp, a notoriously tough nut to crack, trusts Chan not only as a dancer, but as a right-hand woman in the rehearsal room. Chan helped set Deuce Coupe on American Ballet Theatre last season and Tharp’s new A Gathering of Ghosts in October.

Chan is also a member of Pam Tanowitz Dance, and the 2015 Juilliard grad has already performed for two seasons in Mark Morris’ The Hard Nut and danced as a guest artist with the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company. What will she add to her resumé next? —Caroline Shadle

27’52” Henrik Stenberg, Courtesy RDB

Tobias Praetorius

As a young student at the Royal Danish Ballet School, Tobias Praetorius got to perch in a tree onstage during August Bournonville’s A Folk Tale and watch the dancers below, imagining himself in their place. Now 23 and in the corps, he is a mainstay at the company, where he has danced everything from the mild-mannered troll Viderik in A Folk Tale to Benvolio in John Neumeier’s Romeo and Juliet, as well as works by Jiří Kylián, Liam Scarlett and Cathy Marston. But what’s unique about Praetorius is how he embraces all aspects of his craft: He’s equally at home in character and pure dance roles, and is also a budding choreographer.

During a recent appearance in New York City, Praetorius gave a riveting rendition—slithering, androgynous, menacing—of the vindictive witch, Madge, in La Sylphide. A few moments later he was dancing the first variation from the tarantella in Bournonville’s Napoli with total ease, displaying that plush Bournonville plié and relaxed upper body. “I’m happy the Royal Danish Ballet still produces dancers like Tobias,” his former RDB colleague Ulrik Birkkjaer says of him. “That sense of character and storytelling, at that level, and at such a young age, is rare.” —Marina Harss

La Sylphide Kim Kenney, Courtesy Atlanta Ballet

Airi Igarashi

When Atlanta Ballet debuted Yuri Possokhov’s Nutcracker just over a year ago, a then-22-year-old Airi Igarashi gave an opening-night star turn. As a second-year company member, she carried the ballet, dancing both major pas de deux in the role of Marie. Partnered by Sergio Masero-Olarte, Igarashi spun and burst into broad, luminous lines, looping, diving and etching spirals across the space.

Igarashi trained at the Reiko Yamamoto Ballet School in Gunma, Japan, and accepted a Prix de Lausanne scholarship from Hamburg Ballet’s school in 2013. She joined Atlanta Ballet in 2017 after impressing artistic director Gennadi Nedvigin with a variation from Balanchine’s Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux, and her artistry has only grown more compelling since. Her performances in Don Quixote and Bournonville’s La Sylphide have shown the warmth, generosity and multi-dimensionality of a rising ballerina. —Cynthia Bond Perry

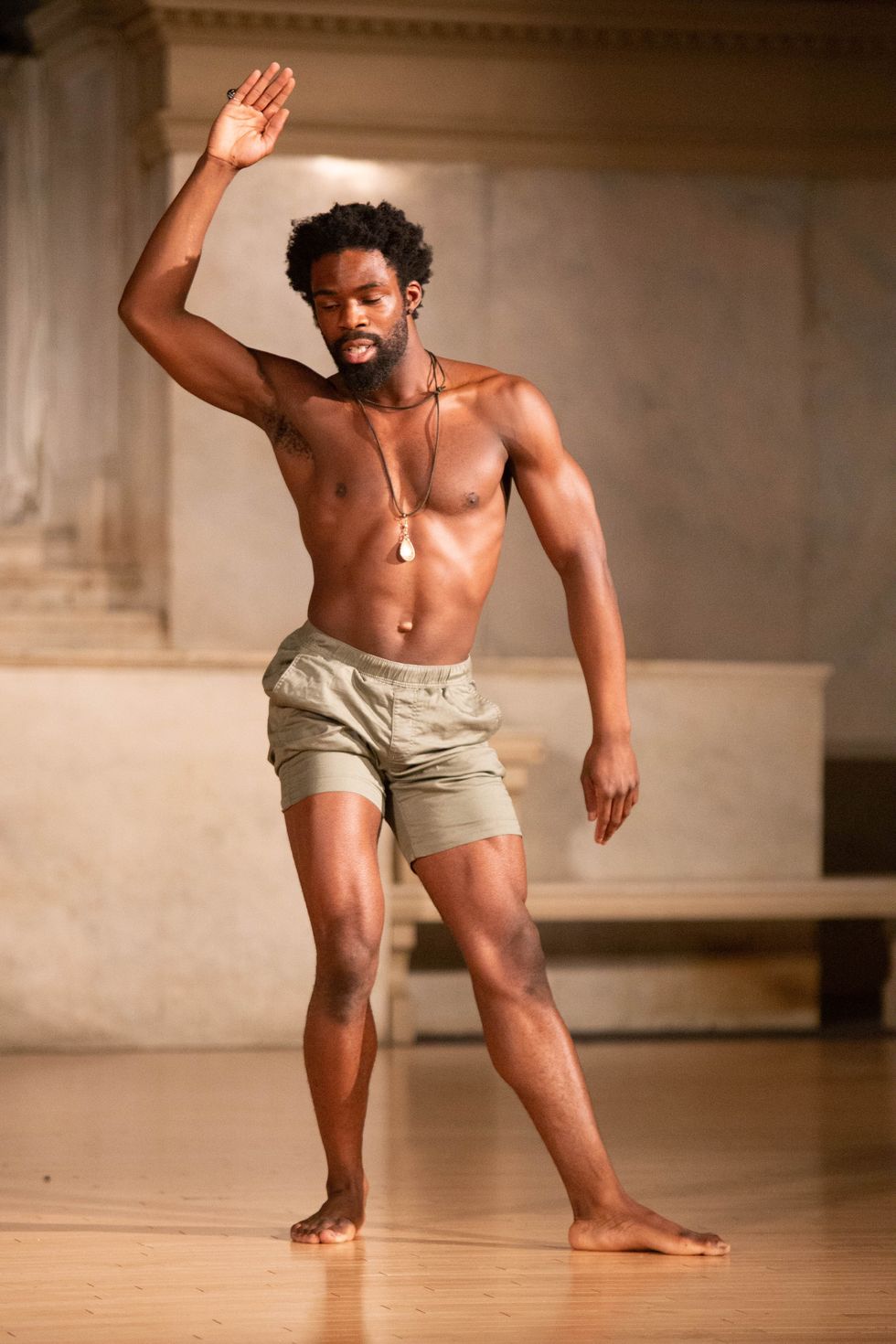

Oluwadamilare “Dare” Ayorinde

Oluwadamilare “Dare” Ayorinde transforms himself each and every time he performs, in pieces by drastically different choreographers. In Trisha Brown’s repertory, he dances as if each work was made during his still recent tenure with her eponymous company; those iconic gliding legs and arms seem fervent and fresh whenever he traverses the stage. For Kyle Marshall, Ayorinde is grounded and pulls from his soul in contemporary works that demand personal dredging of his African-American roots.

His passion is unquestionable, transforming any work brought his way. Recently, Ayorinde has begun to find his own voice in the role of choreographer, seeking to bring his Nigerian heritage to life.

—Charmaine Warren

Credits for header photo, l

eft to right, from top: Loreto Jamlig, Courtesy Desardouin; Todd Rosenberg, Courtesy Hubbard Street Dance Chicago; Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB; Jonathan Potter, Courtesy Carlon; Dallas Koby, Courtesy Edwards; Tony Turner, Courtesy Ayorinde; Jeff Downie, Courtesy GroundWorks DanceTheater; Tom Davenport, Courtesy Milwaukee Ballet; Ryan Duffin, Courtesy Yergens; Maria Baranova, Courtesy Chan; Sachs Grootjans, Courtesy RDB; Andrew Eccles, Courtesy AAADT; Kim Kenney, Courtesy Atlanta Ballet; Jayme Thornton; Jonathan Hsu, Courtesy Crothers; Tristram Kenton, Courtesy ROH; Aimee DiAndrea, Courtesy PBT; Marissa Mooney, Courtesy Taylor; Christopher Duggan, Courtesy Hickey; Gene Schiavone, Courtesy ABT; Michael Slobodian, Courtesy Ballet BC; Courtesy Man; Dean Paul, Courtesy Ensemble Español; Steve Smith, Courtesy Edson; Mike Lindle, Courtesy Garner