After the Breakup: Why These Three Former Couples Still Collaborate

Ending a long-term relationship is never easy, and, for couples connected both personally and professionally, it’s particularly complicated. But as these six leaders explain, it’s possible to cut ties romantically while remaining a creative team.

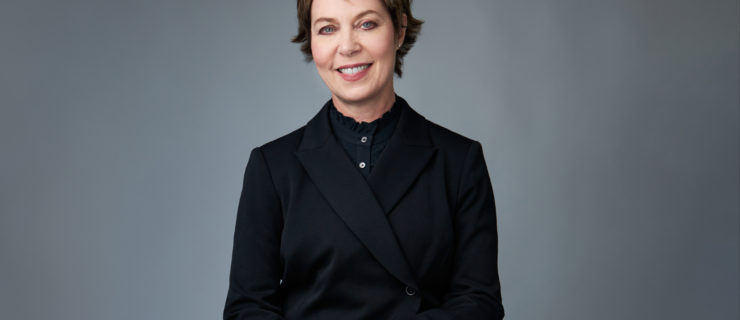

Staying Power: Sheila Lewandowski and Brian Rogers

Co-founders, The Chocolate Factory Theater

They dated long-distance after graduating college two years apart, then reunited in New York City. Together for more than 10 years before founding experimental performance venue The Chocolate Factory Theater in 2005, Sheila Lewandowski and Brian Rogers married in 2007, separated in 2014 and divorced in 2019. “We’d sacrificed a tremendous amount to get where we were,” says Lewandowski, “and made a conscious decision for the organization to exist beyond us.” The two agree the way they run it has never been healthier.

“There were few boundaries,” Rogers admits of the theater’s early years. “Anyone who worked for us entered the vortex of our relationship. While that’s still a dynamic that persists, we’ve worked hard to approach things differently.” That includes clearer distinctions between Lewandowski’s administrative authority and Rogers’ curatorial decisions, and setting rules about dating others within their creative and social circles.

The Chocolate Factory’s forthcoming move to a new building required them to carefully manage expectations and cultivate public confidence. “We both committed to stay through the new facility,” says Rogers, “which was just beginning to manifest as we split up. It was an effort to not dwell in the feeling one of us might destroy the business by leaving.”

They made a six-month plan to tell their staff, audience and funders. In late 2014, on the cusp of the venue’s 10th anniversary, Lewandowski wrote an e-blast summarizing its growth and achievements—and announcing their intention to continue running the venue together after separating.

“When people ask, ‘Did you break up because you worked together?’ I say no,” adds Lewandowski. “If anything, I think we lasted longer because we were working toward something that we both really cared about.”

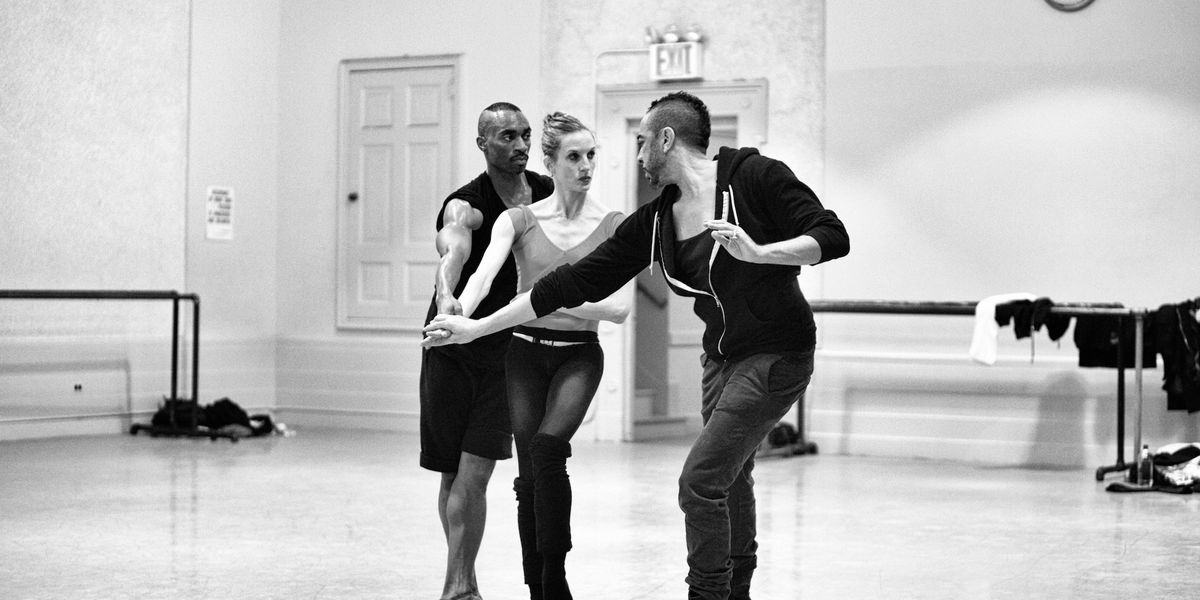

A United Front: Dwight Rhoden and Desmond Richardson

Founding co–artistic directors, Complexions

Contemporary Ballet

Dwight Rhoden traveled to Toronto in 1985 to audition for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and met one of the company’s newest members at a party. Rhoden joined Ailey the following year and, before long, his and Desmond Richardson’s friendship developed into something more.

They launched Complexions Contemporary Ballet in 1994 and dated long-distance using fax machines while Richardson danced in Germany with Ballett Frankfurt. They broke up just as Complexions approached its 10th anniversary but were confident their creative collaboration—and their close friendship—of nearly 20 years could continue. “We didn’t even consider breaking the partnership,” says Rhoden. “We saw the value of what the company offered and knew that it held the spark of our union in ways the relationship couldn’t any longer.” A 2005 article in The New York Times helped them break the news all at once.

“We wanted our audience to know that nothing was changing,” says Richardson. “Sure, either one of us could run the company by ourselves, but it’s the togetherness that makes it interesting.”

“For the dancers, they were like, ‘Who do I go to now?’ ” he says. “And we told them, ‘You go to whomever you want to go to, or come to both of us—we’re both sitting right here.’ A united front was how we always saw it and how it will always be until we’re finished with the company.”

Creative Processing: Sol León and Paul Lightfoot

Choreographers, Nederlands Dans Theater

Creative partners almost since they first met in 1987 as members of Nederlands Dans Theater 2, Sol León and Paul Lightfoot rose together through NDT’s ranks to artistic advisor and artistic director, respectively. (The two depart the company later this year.)

“In the beginning, it was ‘just me’ choreographing,” says Lightfoot, “but we were always creating together.” León notes how difficult it was at first to secure equal billing. “In that time there were not often two creators and not many women, either. It was hard for the system to understand that I wasn’t just his muse. Maybe sometimes he was my muse!”

Still legally married and with a daughter who uses both of their last names, the two separated around 2005. Premieres from that time are perhaps the best chronicle of how taxing the transition was, says Lightfoot. “I hate the word ‘therapy,’ but it did help us resolve our emotional issues. I won’t say we exploited it, but people noticed. ‘I don’t know what your ballet is about, but what the hell is going on?’ ”

” ‘Separate’ is a funny word because we were still together 24 hours a day,” says León. “But the work became quieter because we were not so volatile. ‘You go to your room and work on your pas de deux, I go to my room and work on my pas de deux.’ Everything became much more adult. For the dancers and other people it was actually easier.”