Dancer-Turned-Documentarian Paul Michael Bloodgood Focuses His Lens on the Making of Ballet Austin’s Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project

No other ballet has shaped Paul Michael Bloodgood’s life as much as Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project. He was a young dancer who’d recently joined Ballet Austin when he became part of the physical, educational and emotional process to create this singular work and community dialogue with artistic director and choreographer Stephen Mills and Holocaust survivor Naomi Warren—whose testimony is at the heart of the project.

Ahead of the ballet’s world premiere in 2005, Warren’s fellow survivor Elie Wiesel spoke in Austin. “Not everyone can make history. But it is given to all of us to take part in it,” he said. “And this, I believe, is at least one simple lesson that we draw from our stories: When people suffer, don’t sleep.”

Bloodgood had a chance to step into Light again when it was restaged in 2012 and on tour to Israel the following year. But as Ballet Austin prepares to perform the work March 31–April 2, Bloodgood has retired from the stage and turned to filmmaking, embracing a second career he’s no less passionate about. His first feature-length film, Trenches of Rock, told the story of his father’s Christian metal band whose tour bus was the setting for much of his childhood. “I had always been told, at least when it comes to documentaries, start with what you know,” he says.

Now, he’s trained his lens on another familiar story and formative experience with Finding Light, a documentary that revisits the making of Light in the hopes of spreading its universal themes—of hope and the protection of human rights in the face of hatred and bigotry—to a broader audience.

It’s definitely a tribute to Naomi. Because, to paraphrase Stephen [Mills], her sharing her testimony was a gift. And it was an even bigger gift that she allowed Stephen to create this work.

When 9/11 happened, I was feeling a lack of reason to be, in terms of being a dancer. Entertaining people just felt like a frivolous waste of time, quite honestly. And so what was my purpose in life?

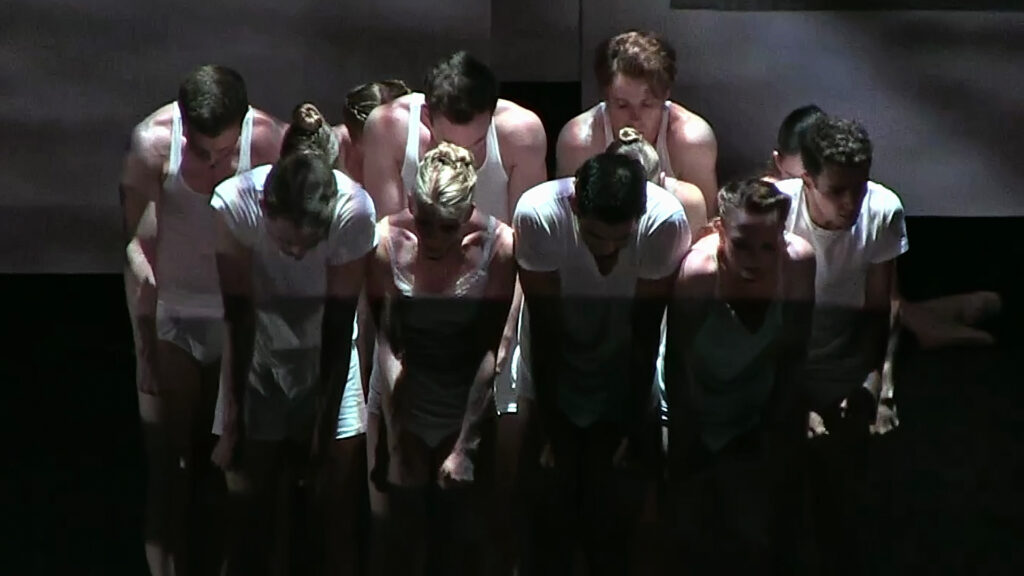

Light was the first time in my career—and really one of the only times in my career—where I felt like I was a part of something so much larger than myself. If you speak to me or any other person who was in the original cast, it’s almost spiritual, the experience that we had.

None of the original cast was of Jewish descent, nor is Stephen. So it became: Why are we making this? Why us? And Naomi, her whole thing was: You have this platform, so you need to use it. The themes of bigotry and hatred and injustice—that’s universal.

This is a conversation that we have to keep having, unfortunately. There’s always a reason for it. Even though it’s Holocaust-based, that’s the underlying storyline. The universal themes can be just about anything to do with injustice. In 2005, it was police brutality in Austin. In Pittsburgh, it was anti-Semitism when they performed it.

My title Finding Light—yes, it’s alluding to the ballet, and how Stephen and Naomi essentially found Light, the ballet. But I like to think of it as we’re all looking to find light in the world.

We have to keep learning from our past. And the only way we can learn from our past is to continue talking about it. We’re constantly passing the torch of the conversation.

What do I want people to take away from the film? That art can be the instigator of conversation that will compel people to action.

In the film, we talk about what we’re going to do when the survivors are no longer with us. And at least film—as long as we do all of our proper backups—it’s immortalized. So now the film can live on indefinitely past all of our lives, and that’s something you can’t do with ballet.

This is my gift back to the dancers who perform the work. For the first time, there’s nobody from the original cast, and there are only a few dancers in the company who even had the chance to meet Naomi. And so having the ability to share this film allows them to get to know her and, in a way, witness her testimony. It’s like allowing her presence and her spirit to be in the room. We have to keep her story alive. And that’s where the film ends—that we continue.