Her Own Words: Joan Acocella, 1945–2024

For several years in the 1980s and early ’90s, before her tenure as The New Yorker’s dance critic, Joan Acocella honed her eye and pen as an editor at Dance Magazine. Both the eye and the pen were already famously sharp: Few writers could better pin down the ineffable, and few seemed happier to argue with the dissidents who wrote letters to the editor.

Tributes to Acocella have abounded since her death on January 7 at age 78. As our farewell, we’ve gathered here choice excerpts from Acocella’s pieces for Dance Magazine.

From “The Bucket Dance Theater…But No Longer at the Bottom,” on the company now known as Garth Fagan Dance (March 1986)

What makes the Bucket an important company is Garth Fagan’s kinetic imagination—the scale of emotional and even philosophical truth that he can locate and illuminate in pure movement….Much of Fagan’s choreography rides back and forth between serene moments…where the soul is joined to the world, and moments of seeming rebellion, of breaking loose—a dialectic that gives his work a strange, nubbly texture, riddled with pockets of mystery.

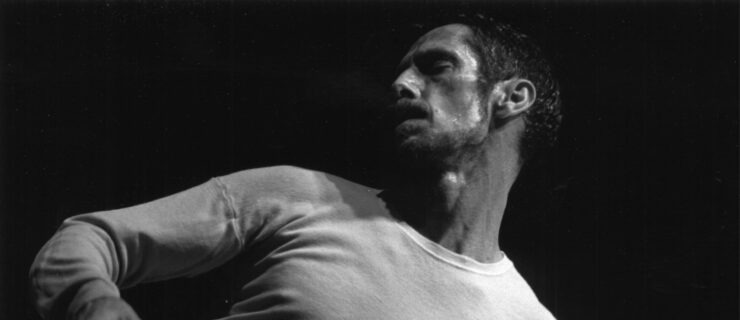

From “Swan Lake On Ice,” a review of New York City Ballet’s spring season, discussing the reconstruction of Paul Taylor’s original solo in George Balanchine’s Episodes (November 1986)

The solo shows choreographic and psychological tension at the point of near breakdown. Peter Frame’s body (which looks a lot like that of the young Paul Taylor) takes stab after stab at sense—extensions, uprightness—and every stab misses. The arms retract, the body falls into a crouch, and the hands grab the legs from the outside, then from the inside, then crossed-over. To make matters worse, the feet then go into relevé, hoisting this tangle insecurely into the air. Between complications, Frame squints up into the spotlight, like a bug caught in the beam of a flashlight. What is being said here is almost unsayable: something comical, pathetic, and extremely horrid about human life. Then darkness, then the Ricercata and the ballerina, to comb the skein.

From “Ashton and Anniversaries,” a review of The Joffrey Ballet at New York City Center (March 1987)

Like the children of a good mother, [Frederick] Ashton’s characters are free to play, to change, to commit sins and follies without being harshly punished. Many people have written about the moral generosity of [La Fille Mal Gardée]: how Widow Simone, though foiled, is not shamed, and above all how Alain, in returning at the end after the wedding party has departed and joyously reclaiming his beloved red umbrella, is really given the last laugh. I think, though, that this generosity is merely part of the atmosphere of freedom that permeates the ballet. Because nature is going to make things okay, Ashton doesn’t have to worry about that. Therefore he doesn’t have to keep track every minute of who’s right and who’s wrong, and what “kind” of people they are….Within the limits of comic convention, each character is its own little horn of plenty.

From “Armies of Angels,” a review of American Ballet Theatre’s Metropolitan Opera House season (September 1987)

Hailing from the libido-and-aggression school of modern ballet, Kenneth MacMillan seemed, at first, a dangerous choice to stage American Ballet Theatre’s new Sleeping Beauty. Would we get another one of those “modern psychological” classics? Would Carabosse be found to have some deeper motivation for her evil? (Oh God, what about the spindle?) Yet MacMillan has produced a grand and decorous staging, with almost no psychology of any sort, but with uniformly excellent dancing….

It was also stylistically consistent—a critical point in the case of this work. The Sleeping Beauty is an authoritarian ballet. Its court stands for the order of the world, a mirror of heaven’s, and, as in heaven, all that is to happen is foretold, in the Lilac Fairy’s prophecy at the end of the Prologue. However remote this ancien régime may seem to us now, it can still speak to us of things that we prize: harmony, clarity, and grandeur. But the medium of that communication is the academic technique. Agreement on that, stylistically, equals agreement on the world of this ballet; classicism as a way of dancing equals classicism as a way of seeing the world. ABT’s dancers agreed and, in doing so, created that atmosphere of sweet security in which the classical dream—that truth is simple, knowable, and beautiful—could, for three hours, come true.

The production, then, is in some measure a celebration of American Ballet Theatre. Is it also a celebration of Aurora’s birthday, and her wedding? Not yet. As I said, the ballet is almost devoid of psychology, and that includes any look of human ease or naturalness. Why are the courtiers so faceless? Why do the fairies wear frozen grins? Why does the Lilac Fairy act like a sorority rush chairman? MacMillan made his name as a realist and certainly, on the evidence of his Mayerling, would seem to believe that aristocrats are human too. It is as if, there being no incest or murder in The Sleeping Beauty, he decided that it was simply not amenable to realism and gave up on that score altogether.

From “In Search of Sacre,” on Millicent Hodson’s reconstruction of Le Sacre du Printemps for The Joffrey Ballet (November 1987)

The original Sacre may have been more mystical in tone than we have been led to believe. (Stravinsky later said that “The Coronation of Spring” would have been a more accurate translation of the title than “The Rite of Spring.”) It is quite likely that the critics and other witnesses of 1913 stressed its brutality at the expense of its exalted character, for the brutality is what would have struck them most forcibly. They were not used to seeing “ugliness” onstage….If we find the reconstruction less brutal than the legend, this will be no surprise. Do we get red in the face and storm out of the picture galleries when we see a cubist canvas by Picasso? People in 1913 did.

I think that there will be controversy about this reconstruction and that the controversy will be a lot of fun. It will also be irresolvable. For there is little hope of separating the “true” ballet from the historical and individual vagaries of perception. Was it the scene of primal terror that [the critic Jacques] Rivière, for example, saw, or was it, as Hodson says, the marriage of earth and sky? Whose Rite is right?

On the other hand, the reconstruction may end up looking just as the original is said to have looked. And the ballet may come down on us like a ton of bricks, just as it did on the audience of 1913.

From “Balancing Act,” on ABT’s Met season (October 1990)

Throughout [Twyla Tharp’s] work…there are marauding bands. And throughout, there is a childlike fascination with being cool, with mastering hard things—ballet, for example—to the point where they are made to look easy, casual, like nothing. Finally, as an extension of that, there is a preoccupation with order and disorder. Again and again, Tharp will create a scene of chaos which then—snap! on one beat—will reveal an underlying order….

For years she was able with her own company to combine her two loves of order and disorder—how cool and loose those Tharp dancers were! and at the same time, how sharp-footed—but once she met Baryshnikov, he raised the ante on both sides. For he was a ballet dancer—that is, a practitioner of a technique whose very basis was the idea of harmony—and furthermore, the most perfect ballet dancer in the world, an artist of breathtaking precision and probity. Had she sought the world over for an image of order, she could not have found a better one than he. And what did he want? The same as she: to challenge order with disorder, the old days with the new, being European and perfect with being American and cool.

From “Wake-up Call,” a review of Peter Martins’ Sleeping Beauty at New York City Ballet (September 1991)

In [Darci Kistler and Kyra Nichols] New York City Ballet has what no other company, worldwide, has at this moment: two truly great ballerinas. Nichols is the stronger technically, but technical mastery is merely the base on which she builds her art. That art lies in the subtlety of her phrasing….Her small steps are small and perfect—seed pearls. Big steps, when she wants to make them big, are huge. She can knock off pirouettes à la seconde as if she were hitting homers out of the park, four in a row. She is no actress, but in her dancing alone there are a thousand dramas….

[Kistler’s] great gift, unmatched by any other dancer today, is the grand impulse with which she weaves space into time….When, in her variation in the [Sleeping Beauty] grand pas de deux, she raises her arms higher and higher, the image expands in your mind, telling you Aurora’s future. She is not just raising her arms; she is raising flowers, raising her children, raising her bedroom curtains on a lifetime of sunny days. Nichols takes you inward, and you find a whole world. Kistler takes you outward, and you find a whole world.