Steve Paxton (1939–2024): A Lifetime of Burning Questions

A mesmerizing dancer and an intellectual force in the field, Steve Paxton asked basic but foundational questions—about movement, performance, and hierarchies of all kinds. His curiosity led him to become a leading figure in three historic collaborative entities: Judson Dance Theater, Grand Union, and contact improvisation. For almost six decades, Paxton performed and taught around the world, earning the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennial in 2014. Since his death at Mad Brook Farm in Vermont on February 20, at the age of 85, expressions of intense gratitude have appeared across social media.

Paxton grew up in Tucson, Arizona, where he excelled in gymnastics. He also took Graham-based dance classes in community centers. His childhood friend, the critic and educator Sally Sommer, remembers that they “danced at night on the tarmac of empty roads—turned on the headlights and cranked up the radio.” He attended the nearby University of Arizona, where his father was a campus policeman. But he didn’t like the teachers, so he withdrew from college life.

He did like dancing. Paxton accepted a scholarship to the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College the summer of 1958, where he studied with José Limón and encountered Merce Cunningham’s work. That fall, Paxton came to New York City, where he continued studying with Limón and Cunningham. “I regarded myself as a barbarian entering the hallowed halls of culture when I came to New York,” Paxton said at an event at the Walker Art Center in 2014.

When Robert Dunn offered a workshop in dance composition at the Cunningham studio in 1960, Paxton was one of the first five to sign up—along with Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti. A protégé of John Cage, Dunn provided the space for experimentation without judgment. “The premise of the Bob Dunn class,” Paxton said, “was to provoke untried forms, or forms that were new to us.”

From those explorations evolved many of Paxton’s famous walking dances. “How we walk,” as Paxton explained in this interview, “is one of our primary movement patterns, and a lot of dance relates to this pattern.”

In 1961, the young Paxton joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. He loved the company and responded to the beauty and humor in the work. He felt drawn toward John Cage’s Buddhist inspirations and “felt at home” when listening to Cunningham, Cage, and visual collaborators Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

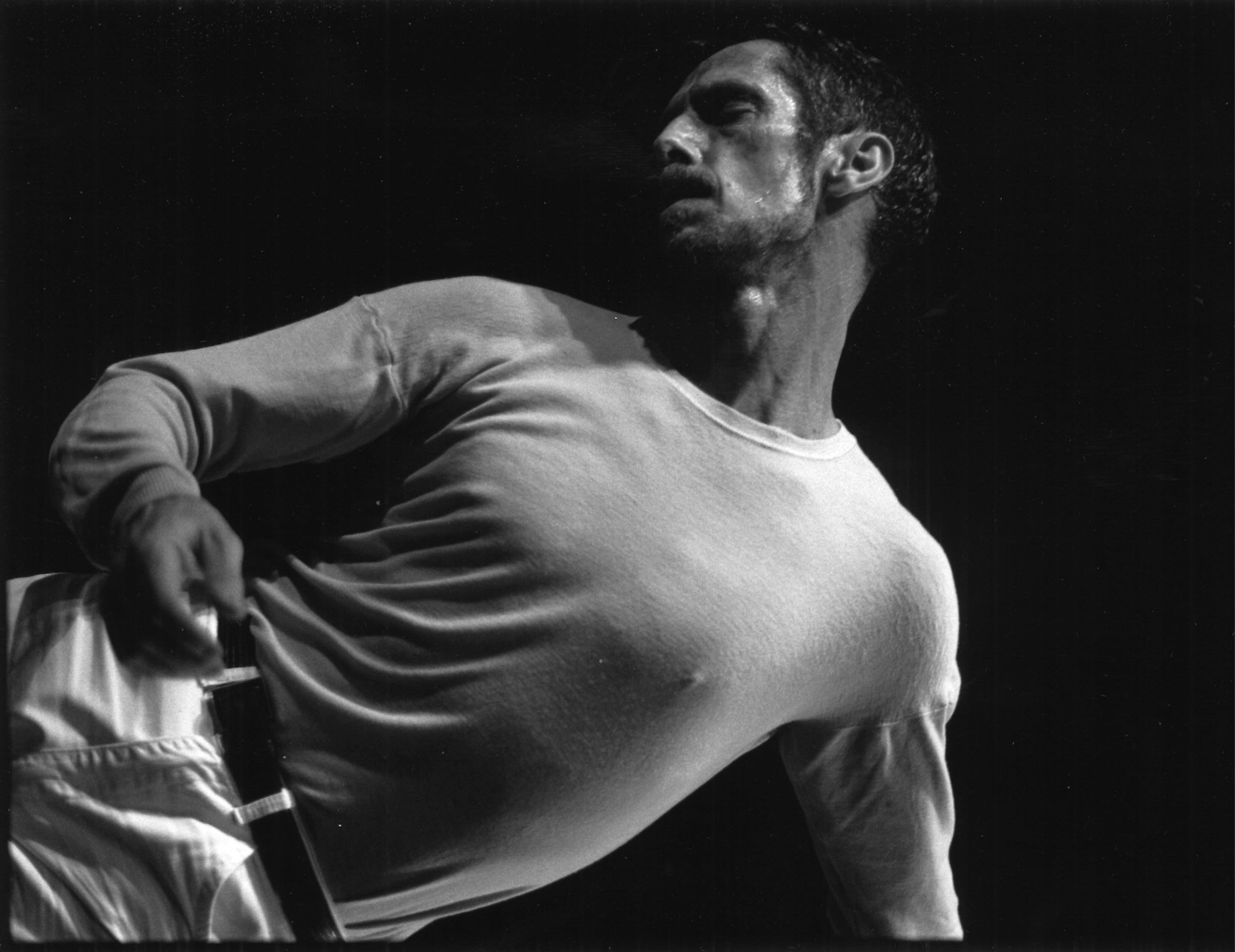

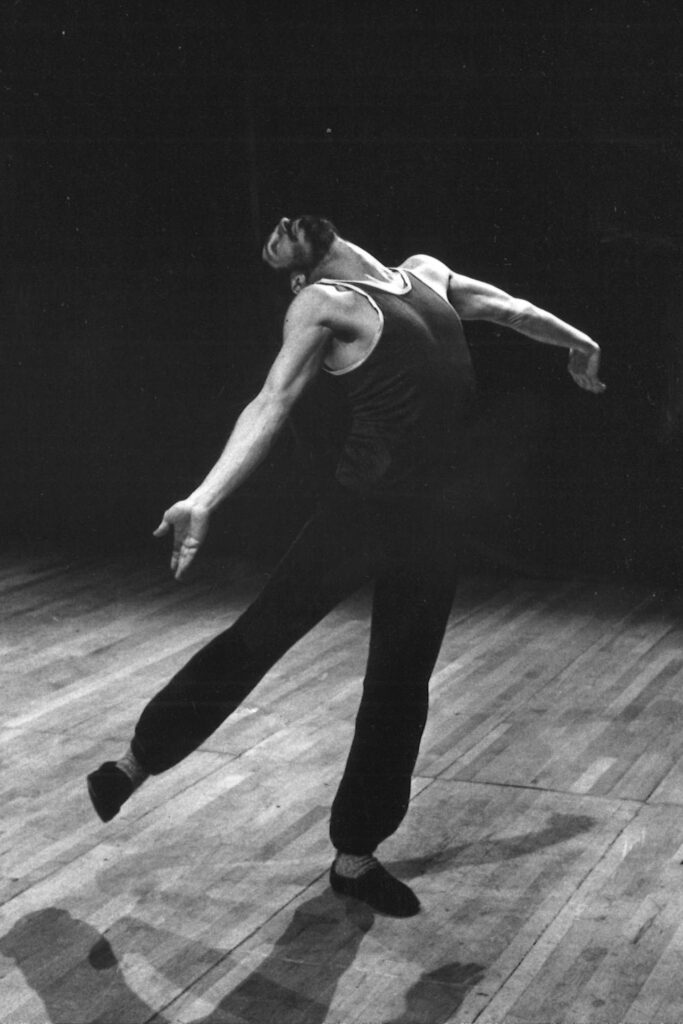

Paxton’s dancing—with his loose limbs, swerving spine, and charismatic aura—was magnificent to behold. In her book Terpsichore in Sneakers, Banes describes him as projecting “a continuing sense of the body’s potential to invent and discover, to recover equilibrium after losing control, to regain vigor despite pain and disorder.” His dancing body was an elucidation of his ideas.

Judson Dance Theater grew out of Dunn’s composition class. From 1962 to 1964, Paxton and a group that included several of Dunn’s other students—Rainer, David Gordon, Trisha Brown, Rudy Perez, Deborah Hay, and Elaine Summers among them—collectively produced a series of 16 numbered concerts, many of them at the Judson Memorial Church.

These concerts marked a historical moment when (portions of) modern dance transformed into postmodern. At the time, Paxton thought of Judson as a place where you could not worry about big entertainment in big theaters and instead just do stuff. Rather than thinking he was doing something revolutionary, Paxton located himself in the lineage of modern dance tradition. In a recent Pillow Voices podcast about Grand Union, he says that modern dance—Graham, Limón, Cunningham, Humphrey, Dunham—gave permission to create new forms “from the ground up.”

Yvonne Rainer wrote about his work at Judson in her memoir, Feelings Are Facts:

Steve’s was the most severe and rigorous of all the work that appeared in and around Judson during the 1960s. […] Eschewing music, spectacle, and his own innate kinetic gifts and acquired virtuosity, he embraced extended duration and so-called pedestrian movement while maintaining a seemingly obdurate disregard for audience expectation.

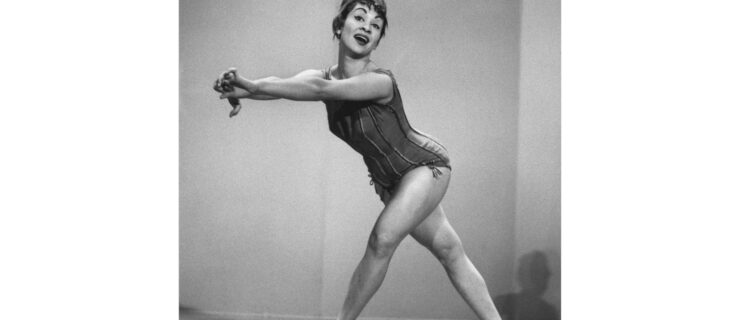

One of the landmark pieces that came out of that aesthetic, which celebrated the untrained human body, was Paxton’s Satisfyin Lover. In it, a large group of dancers simply walked, stood still, or sat on a chair. Jill Johnston wrote this now famous passage in The Village Voice:

And here they all were […] thirty-two any old wonderful people in Satisfyin’ Lover walking one after the other across the gymnasium in their any old clothes. The fat, the skinny, the medium, the slouched and slumped, the straight and tall, the bowlegged and knock-kneed, the awkward, the elegant, the coarse, the delicate, the pregnant, the virginal, the you name it, by implication every postural possibility in the postural spectrum, that’s you and me in all our ordinary everyday who cares postural splendor. […] Let us now praise famous ordinary people.

At the end of the ’60s, Paxton was working with Rainer on her piece Continuous Project—Altered Daily, which changed with every performance. Rainer had given the dancers—Paxton, Gordon, Douglas Dunn, Barbara Dilley, and Becky Arnold—so much freedom that the choreography eventually blew open, obliterating all planned segments. After a period of uncertainty, the group then morphed into the Grand Union, an improvisation collective with no leader. It was then augmented by Trisha Brown, Nancy Lewis, and Lincoln Scott.

“Grand Union was a luxurious improvisational laboratory,” Paxton said in Dance Magazine’s June 2004 issue. “All of us were very formally oriented, even though we were doing formless work.”

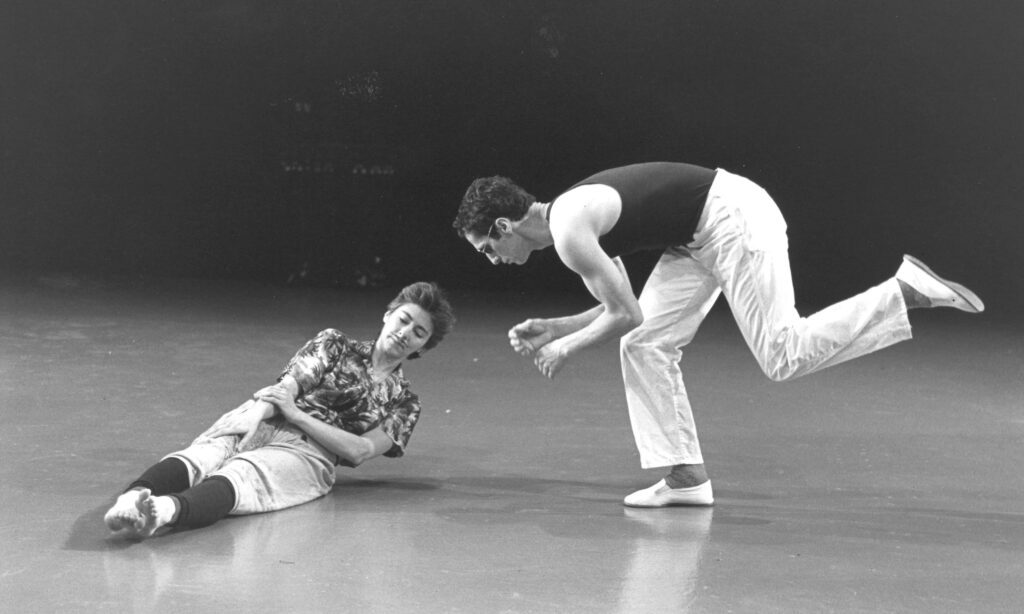

When Grand Union was engaged for a residency at Oberlin College in 1972, Paxton taught a daily class at dawn that included “the small dance.” Nancy Stark Smith, then a student, loved it. “It was basically standing still and releasing tension and turning your attention to notice the small reflexive activity that the body makes to keep itself balanced and not fall over,” she once said. “You’re not doing it, but you’re noticing what it’s doing.” This concept of noticing interior movement became foundational for contact improvisation.

Although Paxton is called the “inventor” of contact improvisation, he pointed to the mutuality of the form. It’s “governed by the participants rather than by a leader, similar to the structure of Grand Union,” he said.

Contact improvisation attracted thousands of people who wanted to move—and move with other people—but who did not want to train to be concert dancers. Paxton was involved in contact improvisation, often with Smith, for 10 years.

Then he started developing his solo works, including his improvisations to Bach’s Goldberg Variations from 1986 to the early ’90s. He went on to develop “material for the spine,” which he described in Dance Magazine as “what the spine is doing in that tumbling sphere with another person—a kind of yogic form, a technique that focuses on the pelvis, the spine, the shoulder blades, the rotation of the head.”

Paxton collaborated with Lisa Nelson, his life partner and fellow improviser extraordinaire, on two entrancingly improvised duets: PA RT (1978) and Night Stand (2004). He gave workshops all over the U.S. and in Europe. While he wasn’t a warm and fuzzy teacher, he was thrillingly articulate. He never faked enthusiasm. And he was trusted completely by colleagues from the ’60s—Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, and Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown—in a way that I would call pure love.

Paxton always opted for the organic, close-to-nature option. Toward the end of his life, he spent much time in his garden in Vermont. In a talk at the Judson Dance Theater exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018, when asked about his life at that time, he said: “Every atom in the landscape in front of me that I look at every day is changing…I feel like it’s a living soup and I’m…kind of dissolving into its space.” He has now completed his dissolution.

Read an expanded version of this post here.