Coming Out of the Shadow of Colonialism, Hula Today is Experiencing a Renaissance

In a flowing blue-green gown, her arms bare, her long hair swept up elegantly and encircled with blossoms, Kayli Ka‘iulani Carr confidently took the stage at the 2016 Miss Aloha Hula contest in Hilo, Hawai‘i. This was the modern portion of a high-pressure contest, and she danced to the aching melody of “Ka Makani Ka‘ili Aloha,” which tells a story of a heartbroken lover who summons a magical, “love-snatching” wind to recapture the heart of his beloved. Carr dazzled the judges, the audience and the social media world.

In the traditional portion, she performed “Eō Keōpuolani Kauhiakama,” a dance celebrating the highest-ranking wife of King Kamehameha I. Draped in volumes of gold cotton stamped with scarlet and black patterns, she opened with an oli kepakepa, a rapid-fire, conversational chant.

“It’s really fast and really long, and you have to get a lot of words in at one time; then comes the challenge of having emotion with those words,” Carr told the Honolulu Star Advertiser after her win. “Not just speaking fast, but speaking with a purpose.”

The video of Carr’s performance went viral, and if you want a taste of hula today, you need go no further than the YouTube clip. Forget Hollywood images of lithe women in coconut bras and grass skirts. Forget the made-for-tourists Kodak Hula Show in Waikiki, which provided one version of hula for 65 years before shutting down in 2002. And forget “The Hukilau,” the hapa haole, or half-English hula, that is commonly trotted out at commercial luaus.

The Essence of Hula

Real hula is primal, archetypal, esoteric and ever- evolving. And it’s now shared digitally all over the world. This is a good thing, because it helps authentic hula spread, not just via more hula schools (called “hālau hula”), but also through conferences, theatrical performances and festivals in the 50th state, the continental U.S. and Japan. You can find performances at Wolf Trap, Carnegie Hall and the National Museum of the American Indian. And even at the most touristy venues, you can witness stunning hula practitioners like Carr, who has danced in the luau at O‘ahu’s Sea Life Park.

The Miss Aloha Hula contest is just one event at the Super Bowl of Hawaiian dance, the 59-year-old Merrie Monarch Hula Festival. Usually held the week after Easter, the Merrie Monarch attracts thousands of spectators for its acclaimed hula competition, Hawaiian arts fair, hula shows and grand parade through Hilo. Many more watch the event from afar, as it is streamed live on the web. And still more follow it on social media.

At competitions, schools of traditional dance compete in two major categories: Hula kahiko (“ancient dance”) features powerful movements and rough percussion; performers adorn themselves with skirts made of bark cloth or ti leaves and with garlands made of flowers, ferns, nut and shells. Hula ‘auana (“wandering hula”) is the lyrical, graceful style danced to the music of guitars and ukuleles; costumes range from the long skirts and high-neck blouses of the Victorian era to the jeans, T-shirts and backward baseball caps of today.

Yet as exciting—and affirming—as contests like the Merrie Monarch are, many hula practitioners avoid them. Some even see the competitions as distorting hula by placing undue emphasis on crowd-pleasing poses and memorable attire.

Rejecting Colonialism

The “Merrie Monarch” in the title is King David Kalākaua, who revived the ancient art of hula during the 1880s. “Hula is the language of the heart and therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people,” Kalākaua once said. In ancient Hawai‘i, hula expressed the intimate relationship between man and nature, the everyday and the divine. Humans were siblings to plants, and all things possessed spiritual presence, or mana. One could talk directly to the winds—or swim with fish and be among departed relatives.

To symbolize their relationship with nature, dancers wore ornaments crafted from the natural world. But it was words that defined the dance. Hula was the history book of a people without a written language. Chants ranged from sacred prayers and encomiums to chiefs, to love ballads, to odes to favorite places. Then there were the mele ma‘i, or “procreation chants,” which celebrated—indeed encouraged—unbridled eroticism.

It was the hula ma‘i that troubled the missionaries who arrived from New England in 1820, eager to spread the word of their god—and to dominate island politics, commerce and culture. They quickly denounced the hula as heathen. But after a 50-year dormancy, Kalākaua elevated the hula, hoping it would shore up a culture battered by disease and colonialism. He and others wrote new Hawaiian poetry and arranged it into stanzas, melodies and tempos (including waltz and polka). String instruments and even piano were enlisted to soften Hawaiian percussion, like gourd drums, feather-decorated gourd rattles, split-bamboo rattles, sticks and stone castanets.

Kalākaua couldn’t have guessed that hula’s domain would widen so dramatically. It became a key part of the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, as Native Hawaiians sought not just to restore Hawaiian culture but also reanimate it. By the end of the 20th century, hula would claim pride of place alongside hip hop, Cajun, tango and other popular forms of world music and dance across the U.S.

Movement as a Message

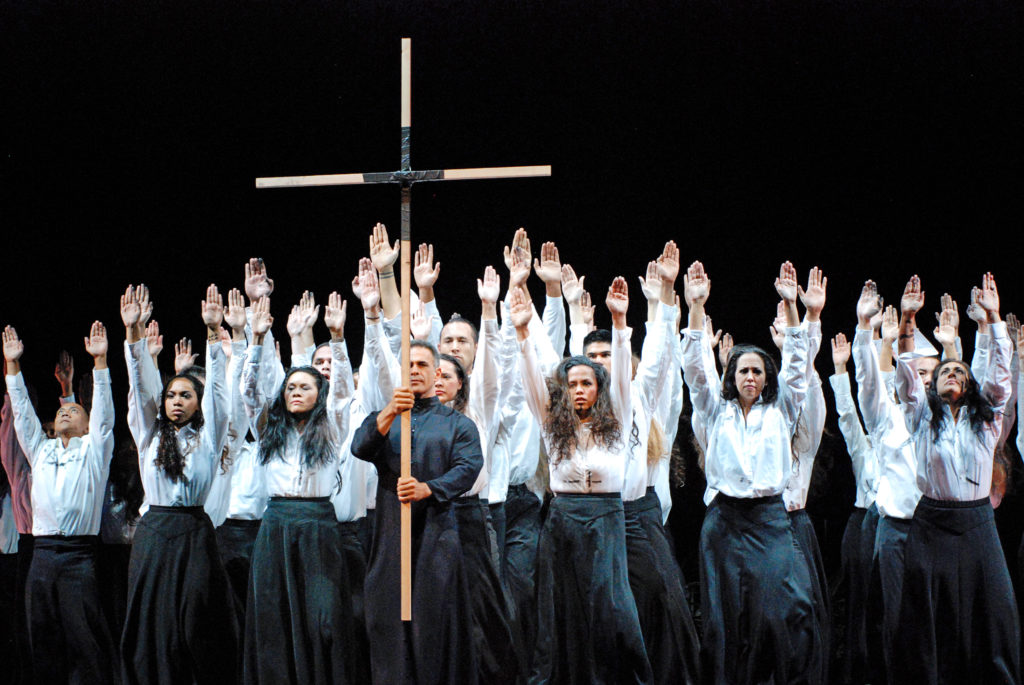

Some hula masters are experimenting with the form itself, choreographing dances to nontraditional music, say, or creating longer dramas that address contemporary issues, like AIDS and immigration. “Salva Mea,” an iconic excerpt of the larger work The Natives Are Restless, by Patrick Makuakāne, a kumu hula (master hula teacher) based in San Francisco, takes on the brutal colonialism of the missionaries.

Others are choreographing full-length dramas. Hānau Ka Moku is a large-scale hula production created by Tau Dance Theater with a renowned family on Hawai‘i Island, the Kanaka‘oles, who count eight generations of chant and hula masters in their lineage. For the work, they grafted traditional elements of hula (sharkskin drums, chants for the gods) with elements of modern dance (dancers roiling and kicking within a giant, stretchy red sock suggest moving, molten lava). The results range from the comical to the ethereal.

Amy Ku‘uleialoha Stillman, a University of Michigan professor and musicologist, cites the proliferation of such pioneers as one of the most striking phenomena in hula today. “More kumu are taking alternate paths away from competition and toward theatrical spectacles,” she says, citing Makuakāne (my own kumu) along with island entertainers and educators like Micah Kamohoali‘i, Kuana Torres Kahele and Taupōuri Tangarō.

Tangarō is part of the Kanaka‘ole family; his Unukupukupu institution at Hawai‘i Community College in Hilo shows how the practice of hula has moved far, far beyond the dance class. “Unukupukupu” means “Shrine of Ferns Rooted in Fresh Lava,” and the name is anchored in the explosive Kanaka‘ole dance traditions. It was created, Tangarō says, “not to replace the hālau, hula school or hula studio,” but to “meld deep culture and higher education” and to teach the rituals that connect us to nature and our ancestors. The goal? To encourage us to become advocates of “environmental kinship.” The idea, he adds, is to grow awareness and foster actions to keep our sacred lands—and the sacred lands worldwide of our students—“pure and undefiled.”

Unukupukupu is hardly the only traditional school of hula to teach environmental stewardship, among many other things. Makuakāne’s hālau, Nā Lei Hulu i ka Wēkiu, regularly invites Hawai‘i scholars, activists, craftspeople and composers to give lectures and workshops.

Tradition Meets Innovation

Hula has adapted to the pandemic in sometimes unexpectedly rich ways. Performances have been canceled or taken outside, and classes have moved online, both a blessing and a curse for students. Makuakāne devoted himself to building a new “altar” each week in the room where he taught classes on Zoom. This was an innovation on the traditional hula kuahu, the altar built to celebrate Laka, the divine essence often called the “goddess of hula.” (The kuahu and the chants offered to it summon her to inspire dancers to invest power and meaning in their practice.)

To build the new kuahu each week, Makuakāne foraged among the ferns in his garden and took trips to the flower market, dragging in drums, draping fabric and placing mementos. He launched each class with a chant, often placing a lei in a spot of honor. Makuakāne’s kuahu were informal, though, intended mostly to help the dancers shift focus at the end of a pandemic day, escape from the monotony of Gallery View, enter a consecrated space and spend a special hour and 15 minutes with a hula community.

“I’m using the kuahu to engage my haumana (students) in this platform we’re stuck with,” he says. “I want to have a higher-level communication with the people in this room with me.”

Other kumu hula have also searched for new teaching paths during the pandemic. Some turned to teaching workshops outside Hawai‘i, exposing more people to their own artistry and expanding the base of hula dancers. Others began to teach online. Stillman notes that this has “made serious hula instruction accessible, removing geographical barriers, and showing kumu how much hunger there is for knowledge.”

The Hawaiian word for knowledge is ‘ike, and the word is the foundation for the Hawaiian proverb “Ma ka hana ka ‘ike” (“Through doing, one learns”). And this may be the most exciting development in hula today: not the fancy footwork or the innovation in styles or the increasing sophistication of performances, but the idea that more and more and more people are engaged in the totality of the practice, in the quest for ancient wisdom.

Glossary

hula kahiko

“Old” or “ancient dance,” in which chanting is accompanied by sharkskin drum, double-gourd drum, or hollowed-out log beaten with sticks. Some hula kahiko honor gods and tell legends; others honor chiefs or praise places.

hula pahu

The pahu is the carved wood and sharkskin drum once considered especially sacred. This is the style of dance prevalent before Europeans came to Hawai‘i—primal, percussive, sexual, and powerful.

hula ku‘i

Ku‘i means “to join, stitch, splice, or unite,” and refers to the hula of the late 1800s, which stitched together the musical and dance vocabularies of old with new elements from indigenous and Western cultures. The dance became more secular and less rooted in Hawaiian spirituality.

hula ‘auana

Literally “wandering hula,” the graceful, sensuous, and playful hula that evolved after the monarchy years. Often praises aspects of a secular world: handsome ships, a queen’s diamond ring, the “famous fireman” of Honolulu, or a trysting spot for lovers in Waikīkī.

hula mua

Mua means “forward,” and this termis used for Patrick Makuakāne’s new style, pairing Hawaiian traditions of storytelling-through-movement with non-Hawaiian music, from the “Flower Duet” by Léo Delibes, to “Bow Down Mister” by Boy George, to “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” by Tony Bennett.

‘aiha‘a

The ‘aiha‘a is to hula what the plié is to ballet. It refers to hula’s low-to-the-ground stance, knees deeply bent.

kāholo

“Vamp” movement most people associate with hula, when the dancer moves side to side, following a 4/4 beat, letting the hips flow. There are eight basic hula steps, and many more advanced ones.