How Kate Ladenheim's New Video Series Tackles Women's Internalized Misogyny

It’s a standalone dance film series, a nuanced examination of contemporary feminism and an evocative teaser trailer for an upcoming performance—it wouldn’t be a project by Kate Ladenheim, artistic director of The People Movers and one of our “25 to Watch,” if it wasn’t daringly ambitious. Glass is the multi-hyphenate’s latest creation, a four-pronged project about women living under glass ceilings that, in its most widely accessible form, is a five-part video series, the third installment of which was released today.

What are the double standards that come into play when women try to break glass ceilings? What is the backlash when they fail? What happens when they stand together in solidarity, or when they unintentionally perpetuate misogyny? These are some of the questions the film series asks as four dancers protest in pantsuits, conform in deconstructed hoop skirts and pause to paint their nails. We caught up with Ladenheim to discuss the ongoing project.

What is

Glass?

There are four main forms: a five part series of online films, a film and performance installation, a live performance and a dialogue series. My original idea was that I would build a glass ceiling that an audience would stand on and look down on a community of women. But it’s really expensive to build a glass ceiling! And difficult, and dangerous if you don’t do it correctly. We had to find ways around this idea and expressing this inescapable hierarchy women experience collectively. It’s about how you internalize patriarchy against yourself and fellow female identified folk without realizing it when you’re inside that pressure cooker environment.

What led you to create both a video series and a live performance?

There is a stage that everybody looks at all the time, and it’s your phone or computer. There’s something essential about live work, but also about how live and reactive digital spaces have become. If you’re talking about something so reactive as these topics around women and feminism, you need to be there, online. This is a theme in my work in general: the way live and digital work interfaces, and how dance can exist in digital spaces and how that impacts liveness in general. The story can be told in many ways. I don’t really have delusions about myself as an independent dancemaker: My reach isn’t that big, but I like to provide platforms for engagement in a number of different ways.

What is the relationship between the video series and the concert work?

In live work, there’s a way to build tension. You can be more patient with your work in live spaces than in digital spaces, because in digital spaces people get bored. A lot of my pieces are a slow burn, and about things bubbling up inside you and trying to keep it all in. All humans can feel that, but especially women in professional settings where you don’t always feel you can speak up. So in these films, how do we get that feeling without staying in the same place for too long?

Where did the idea for

Glass come from?

I started building the base material in 2015. I had a residency with a composer—Peter Van Zandt Lane—that took place at The Pocantico Center, the former private residence of the Rockefellers. It’s this lavish property, and there are beautiful gardens, but everything is protected by gates. By the end of the week we had the idea that we would make something around the ideas of barriers and gates. And then the 2016 election happened, and the truly disturbing and overt and horrifying displays of misogyny that were plastered throughout this campaign. Hillary Clinton is a woman who is so privileged in every sense, and to have her constantly slandered for her femaleness was really shocking for me. The thought that you can work your entire life for something, be qualified in every sense of the word and just not achieve it because of your woman-ness—that hit me very hard. That’s a barrier everyone can see past but you can’t get through. So this piece was born.

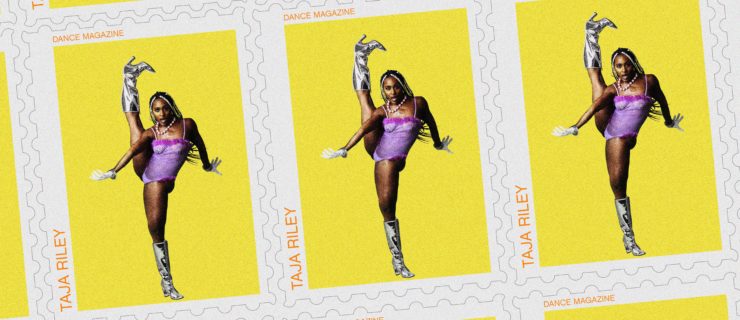

“There are all these skeletons of perceived femininity in the work,” Kate Ladenheim says of Glass. Photo by Whitney Browne courtesy Ladenheim

The costuming choices across the video series so far have been very evocative—pantsuits, deconstructed hoop skirts. How did you arrive at these choices?

The pantsuits pretty directly referenced white pantsuits and political movements and women’s suffrage. The hoop skirts reference restrictive costuming for women that has been throughout the ages. Also, one of the essays by Rebecca Solnit that was inspirational to me was about silence as a series of concentric circles; basically, how silence works as an oppressive tool to keep people from believing women and to keep violence against them invisible. Looked at from above, women in hoop skirts are constrained inside of concentric circles. They stay in the hoop skirts in the rest of the films. They become obstacles: It’s harder to get close to people, you get stuck in them.

What about the nail painting that is so instrumental to

Glass: Part III?

There are all these skeletons of perceived femininity within the work: nail painting and hoop skirts and leotards and nakedness. They all kind of reference these things that women can reclaim for themselves. My mom would get her nails painted every week when I was growing up. I was never really into nail polish. It made me feel overindulgent, ostentatious; even though it’s such a tiny thing, it made me feel like I was attracting too much attention. But it’s something that my mother and a lot of other women reclaim as something that makes them powerful and fierce and sexy—but it’s created by men, with the male gaze in mind. And you can’t do as many things as first when the nails are wet; it affects your physicality in a very specific way. To research for the piece we would paint our nails and do the movement while they were wet to see how it affects our approach.

Something I’ve really appreciated about this series is how nuanced the ideas feel. It’s not just women in solidarity with each other to crush the patriarchy, or, on the other extreme, women putting down or holding back other women.

There’s something I’ve been interested in while watching the discourse around feminism becoming more prominent: Who gets to claim feminism? Nobody is a perfect activist; there is no such thing as an ideal woman. Everyone is trying to become a better person, and I think that’s what the women in Glass are trying to do. Within this structure, how do they relate to each other, the world around each other, express their feelings? It’s not always kind. I don’t think anyone in this world can say someone came to me with a story and I had the perfect reaction, or I gave them the perfect comfort. So there are nuances to the way we treat each other. There are faults to our discourse. There are faults to our attempts at liberation.

Still from Glass: Part I. Photo by Chelsea Robin Lee, Courtesy The People Movers

Has your perspective on this series changed at all in light of the #MeToo movement?

I don’t think it was anything that I didn’t know before it came to light. Of course I know that abuse is rampant. Every woman and queer person that I know has a story around harassment and abuse. So I guess it’s galvanizing to see things coming to the forefront, and it’s exciting to be creating topical work, but I’m not sure that it changed our approach in any way. It was like, Great, everyone caught up!

How do you go about creating a feminist working environment in the studio?

We’re cautious to care for each other. We started with agreements about safety and what I will ask of them and what they can say no to. We all really care about and value consent. I can’t really take credit for that one. I just have the most amazing collaborators, these incredible women: generous, smart, and capable, and really willing to engage on every level. They’re honest and open and I don’t know that it’s me that’s doing it! It’s us that’s done it.

It’s so funny because there’s so much violence and pettiness and passive aggression in the work, but if you saw us you’d never believe we could do that to each other because there’s so much love and care and admiration between us. I’m so honored they work with me! That they think I’m worthy!