What Dancers Can Learn From La Meri’s Focus on the Global Spectrum of Dance

When I came back to taking dance classes after a 37-year lapse (which I do not recommend), I returned to ballet. It’s the foundation. Right?

Gradually I added in contemporary, Pilates, Gyrokinesis and a sprinkling of yoga.

It looked like the equivalent of the food pyramid for dance, which is reflected in the curriculums of most performing arts high schools and college dance programs. Up until fairly recently, the hierarchy remained firm: ballet, modern, then everything else (that is, if you could find an adjunct to teach hip hop, African or classical Indian dance).

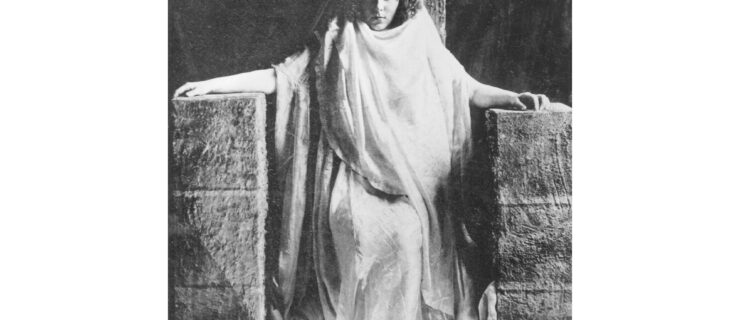

While I was maintaining this Eurocentric line of study, I was also deeply immersed in the work of La Meri, the first American to travel extensively to learn dances from all over the world and perform those dances back to the world. La Meri was looking right at me when she said, “Ballet is just another form of dance,” in documentary video footage I recently viewed at the Jacob’s Pillow Archives.

La Meri, born Russell Meriwether Hughes in 1899, practiced using non-habitual movement patterns to freshen neural pathways way before anyone knew it was good for us, way before somatics and cross-training touted the value of a varied movement diet. Besides dancing, she played the violin, wrote poems, sang, played tennis, swam and rode a horse. In fact, one of her first dance performances involved a horse. She was fond of saying it was the first performance for the horse, too.

She started dancing in her neighborhood ballet studio in San Antonio, Texas, her family’s adopted hometown after they left Kentucky. It would be at Miss Molly Moore’s School of Dance where she would learn her first Spanish dance. She went on to traipse the globe as a solo performer, learning dances from India, Japan, Myanmar, Latin America, the Philippines and Hawaii, to name a few, and created a contemporary vocabulary that sourced these forms from around the world. In 1940, she started the School of Natya in New York City with none other than Ruth St. Denis. Although their approaches diverged, with La Meri being the self-taught scholar of dance forms, and St. Denis being immersed in the spirituality of Indian dance, they remained great friends.

Sure, as a white woman of privilege, we can interrogate La Meri’s authenticity in light of today’s ongoing discussions on cultural appropriation and permission seeking. Yet she cared deeply about learning as much as possible about what she was presenting onstage. She had an ability to grasp the architecture of a form and understand its principles, and an equally impressive ability to switch from one style to another. Her dancing and global savvy afforded her a remarkable career longevity, which was relatively free of major injuries. For three decades, she taught at Jacob’s Pillow because Ted Shawn believed her offerings fit his idea of a rich dance education.

Though a 16-page spread on La Meri appeared in the August 1978 issue of this magazine, we would need to wait until 2019 for Nancy Lee Chalfa Ruyter’s rigorous biography La Meri and Her Life in Dance. Her life and career point to the fact that there are many classical forms that can be just as foundational as ballet. We just don’t see them that way because of a Eurocentric bias.

If I can borrow a term from Liz Lerman, we need to get horizontal here, flatten the hierarchy, and trust in a global spectrum of dance forms, where every style of dance has intrinsic value. What if we imagined some kind of radical restructuring without a bias?

This is already happening. We only need to consider how Aakash Odedra’s training in kathak and bharatanatyam allowed him to seamlessly slip into contemporary work. Then there’s Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s global mix-mastering of forms, and Hervé Koubi’s work with Algerian hip-hop dancers.

As I write this, academia is scrambling to dismantle the ballet/modern hierarchy, and some have been well on their way for years now. But dancers need not wait—one upside of the lockdown is the sheer volume and range of classes now available online. I wonder what will change in our thinking when our moving becomes less tied to the ballet/modern duality. Will we not only gain more neurological flexibility, but refine our individuality as well? Will we have longer dance careers?

There will be resistance. Embracing a larger definition of “technique” takes work. We shouldn’t make dancers’ lives harder, but we can make them different. Let’s be inspired by La Meri’s appetite to take the world into her dancing body.