Choreographing Shouldn't Be a Narcissistic Endeavor

I spend a lot of time reflecting on the direction dance is heading. How do we chart the trajectory of our field? Simple: Through the choices we make when crafting our seasons, the works and choreographers we invite to be part of our repertoire. Fostering the creation of new art is the most important responsibility of every artistic director.

But at times, I feel that choreographing has switched from a means of human communication to a self-centered, narcissistic exercise. This is no doubt a reflection of our world: We live in an era where everybody is the protagonist of their own story on social media.

Sometimes I see choreographers making works that are more about themselves and less about the people who are going to see them. I believe that making ballets is not about being the center of the story but rather making everything but ourselves the center of the story. (Believe me, nobody likes to hear someone going on for hours about themselves…) There’s nothing wrong with expressing our feelings or opinions about a particular subject matter through the dances we create; this is the essence of art. But I draw the line when a piece feels more like it’s lecturing than communicating.

When I watch Broadway shows or a great classical ballet, the choreographer’s attempt to communicate with an audience is palpable. Whether it’s Hamilton, Giselle or Onegin, you are entertained and moved. Even in the case of Mr. Balanchine, arguably the most successful abstract choreographer of all time, his works always touch you. His musicality, sense of aesthetic, pace, textures and colors communicate something universally identifiable by human senses and emotions. He made them for us!

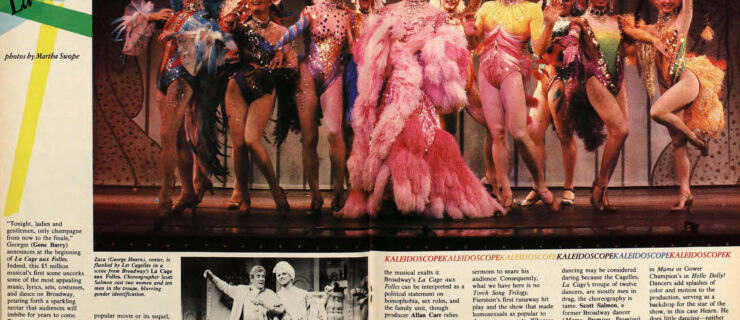

Artistic director Marcello Angelini teaching class at Tulsa Ballet.

Artistic director Marcello Angelini teaching class at Tulsa Ballet.

Courtesy Tulsa Ballet.

How do you know when a work is self-centered? At a certain point during the performance you will find yourself fidgeting. Your mind will wander off, you will slump in your seat and, if you care to discreetly look around, you will realize others are doing exactly the same. They are disengaged. In retrospect, you may think about the work intellectually and be unable to find anything wrong with it. The movement value and structure were good, and the flow was decent. But love and passion are not perceived intellectually. They are experienced emotionally, and emotions never lie!

If I were to give my two cents to young choreographers, I would tell them to use their work to create a dialogue with the audience: Give them something personal, something dear to you. Choreographing should be an altruistic endeavor. It’s a means to an end, and the end is the audience for whom we are creating.

Just as politicians should ideally work for the people, we ultimately work for our audience. We lead them, we educate them, we dialogue with them, we grow with them and, above all, we share our journeys with them. Sometimes we aim to entertain, other times we challenge.

Relevance is in the numbers—selfish works don’t engage an audience, or fill seats.