An Inside Look Into Author Marina Harss’ New Biography on Alexei Ratmansky, The Boy from Kyiv

Ever since she saw The Bright Stream in 2005, the dance critic Marina Harss has been fascinated by the choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, who was then the artistic director of the Bolshoi. In 2009, Ratmansky became the artist in residence of American Ballet Theatre, giving New York City–based Harss the opportunity to track his career up close. “I knew from the minute he moved to New York he was the person, the artist, I was most interested in following,” she says. “At some point, I formed the idea: One day I would love to write a book about this artist.”

In 2016, a performance of Serenade after Plato’s Symposium inspired her to start. “I was so excited by that work,” says Harss. “It felt like he had reached a new level of mastery in the way he was able to depict conversation and thought.” She wrote to him that very night. Ratmansky was generous with his time and access, so Harss dove into research. In 2019 she received a fellowship from the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University that allowed her to begin writing.

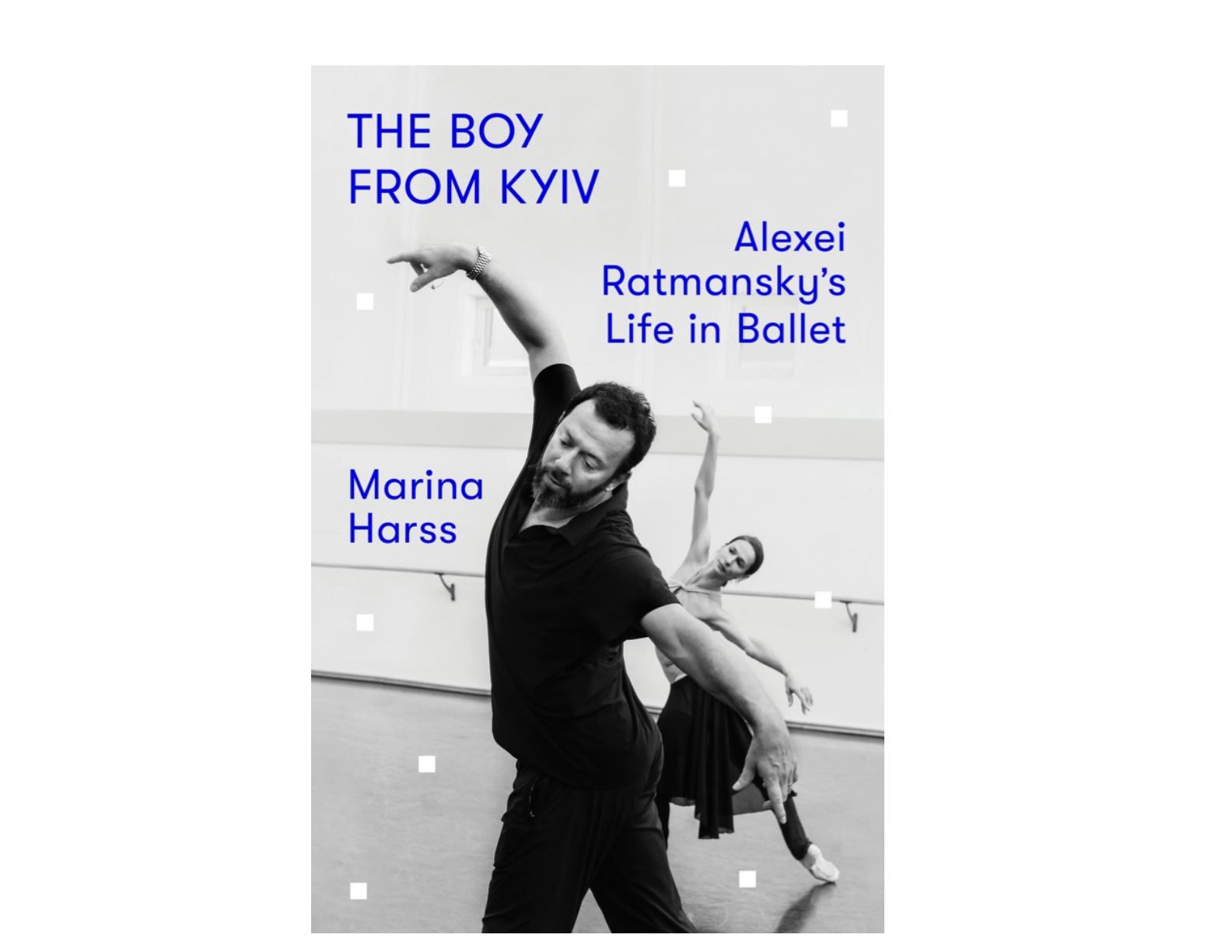

Just as she was wrapping up her book, the COVID-19 pandemic, and especially the Russian invasion of Ukraine, upended Ratmansky’s life and forced Harss to recalibrate—and even retitle—her text. Her biography, now called The Boy from Kyiv, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, is scheduled for release on October 3.

Your book was nearly due when the world fell apart—Ratmansky’s world in particular. How difficult was that?

It wasn’t difficult, but it did require a complete rewrite! I waited a while, until the situation of the war became more clear. Then I realized that it wasn’t just about writing a new ending, because the war clarified something about his identity that had never been clear to him before. It was a significant internal shift. Every time we’d had a conversation about “Where do you feel like you’re from?” the answers had always been this idea of being an internationalist and “My world is ballet.” But then, suddenly, home meant where his parents are, where his sister is, where his wife is from. And I realized it was a theme I had been wrestling with earlier, because I felt that there was more to his Ukrainian identity than he was letting on. In fact, it was lying right below the surface. He didn’t even fully comprehend it. So I had to go back through the whole thing and basically listen to it. The weight of certain things became more apparent.

You show how Ratmansky’s been working in multiple ballet languages his entire life. You speak several languages and have an extensive background in translation. Did writing this book tap into a similar process?

I feel that my background does “translate” [laughs] into my dance writing because I’m translating what I see onto the page for a reader. Though I think one of the interesting things about dance is it doesn’t require words. What’s wonderful about it is it communicates across linguistic and cultural barriers. That said, I do believe that Ratmansky translates what he learns in one place and applies it in another. Bright Stream is both a translation of his Bolshoi training and a translation of Bournonville—what he learned in Denmark about mime and about being natural onstage and about petit allégro. Because he’s been so multinational, he can draw on all these dance languages and combine them into a new one. I guess you could say it’s like Esperanto—a new language that contains all the old ones.

You mention his big, recent move to the New York City Ballet in your epilogue. Is it hard to let go at this point?

Everyone who has seen his work at different stages in his life knows that stage, but almost nobody has the whole picture because he’s moved from place to place. I hope the book will be helpful for people to understand where these different stylistic elements come from and how they fit together. Who is this person who wants to and is able to create this weird combination of humor and humanity and warmth and structural solidity and bravura? It’s a mosaic that then becomes a portrait. It’s the perfect time to end because it’s the end of Act III, we’re entering Act IV. I’m not going to stop being interested in his work, for sure, and I’m going to keep writing about it. I think following the career of a person so closely is one of the most interesting things you can do as a critic and a writer. It’s a profound and stimulating process.