Maternity on the Marley

During the first weeks of Boston Ballet’s 2014–15 season, I began preparing for the most challenging role I could imagine: I was going to be a mother. To stay in the best shape possible, I took class every day, working on all the elements of technique that my changing silhouette would allow (mainly, footwork and port de bras), and kept up a schedule of low-intensity cardio. Even on the day I went into labor, I gave myself a barre in the kitchen and did 30 minutes on the elliptical.

There was a time in the ballet world when pregnancy and dance were mutually exclusive, one virtually mandating the absence of the other. That day is gone. The understanding of the dancer body is evolving, careers are getting longer and audiences and dancers alike now appreciate the artistry that develops through the process of motherhood.

Photo by Igor Burlak.

But it’s not easy. “Pregnancy is a time of tremendous anatomic and physiologic changes,” says Dr. Bridget Quinn, one of the physicians on Boston Ballet’s medical team. Your ligaments get looser. Your center of gravity changes. You become short of breath more easily. Your body needs more nutrients and requires more rest after physical activity. It’s a lot for a dancer. But with diligent training, you can prepare for both a healthy labor and a quick recovery.

Cross-training While Pregnant

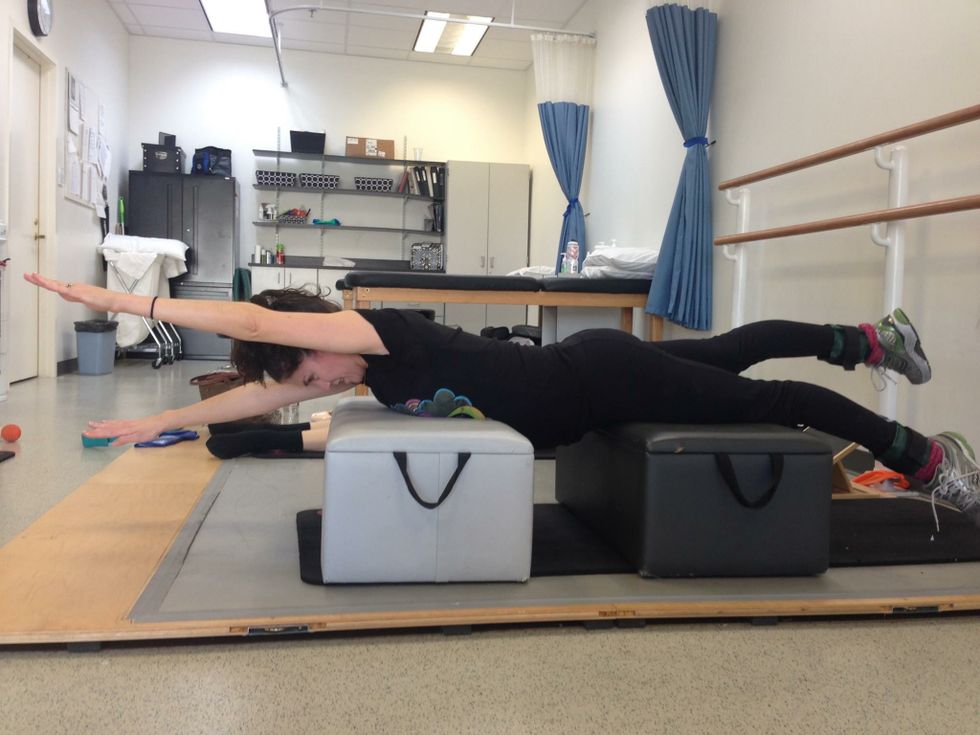

“Dancers are so used to pushing through physical issues like fatigue and pain, but pregnancy is a time to listen to your body,” says Heather Southwick, director of physical therapy at Boston Ballet. She suggests pregnant dancers take up swimming for its low-impact cardiovascular benefits and its ability to increase circulation, muscle tone and endurance. She also tells dancers to practice ballet steps in the weightless pool environment. On drier ground, she recommends side-lying exercises to work hip abduction and gluteal strength, allowing for greater hip stability during recovery.

As the weight of the baby shifts your postural alignment, the spine can begin to sway painfully. For this reason, Marika Molnar, director of physical therapy for New York City Ballet, suggests practicing prenatal Pilates to help maintain proper spinal alignment and pelvic placement.

Mostly, dancers need to be aware of what their changing bodies can handle. I was told I could largely keep my pre-pregnancy routine as long as I was working within my limits. As I took class, I remained mindful of my shifting center of balance, my turns gradually became relevés and I stopped jumping after 20 weeks as directed by my PT. I also drastically slowed the pace of cardio workouts, and made sure to stretch my hip flexors and psoas to maintain flexibility and take pressure off my lower back.

Post-Delivery Work

After the baby is delivered, Southwick suggests dancers pay extra attention to the muscles in their pelvic floor. These muscles, important for balance, stability and continence, undergo significant stress during the carrying and delivery of a baby—the area can become weak and stretched as early as 12 weeks into your pregnancy. Prolonged contractions of these muscles as well as quick pulses while sitting or walking will help strengthen them. I made a point to do at least 10 quick and 10 slow pelvic contractions every breastfeeding session—this paced out the work and ensured consistent daily improvement.

While traditional core work is discouraged for the first six weeks postpartum, the knitting together of the abdominals can begin almost immediately following most pregnancies. Starting three weeks after my labor, I began each morning by doing a modified Pilates 100s while lying flat on my back, with my feet, legs and head on the floor. I used only my breath to engage my abs as they gradually regained their ability to function. By the time my son was six months old, they felt stronger than ever before.

Today, I also feel like I am a better dancer than ever before. It took me three months to recover to full rehearsal duty at Boston Ballet, and after two more, I was back onstage as our season opened, feeling so excited to perform. Having my son has given me a fuller arsenal of life experience to draw from, plus a new awareness of the physical work involved in making a ballet body.

Breastfeeding Posture

A focus on strengthening the shoulder girdle (the muscles between your shoulder blades) is paramount for preparing the body for the not-so-balletic postures of breastfeeding. As I began walking on the treadmill during my recovery, I would engage my traps and parascapular muscles by doing a five-minute series of arm and back exercises—it not only improved my posture but kept me entertained on the treadmill.

Tip: Marika Molnar also suggests adapting your breastfeeding posture by supporting your arms with pillows, for example, to improve your upper-body placement.