Want To Be a More Musical Dancer? Develop a Versatile Relationship to the Score

When we think of musicality, we often imagine fleet-footed dancers who can cleverly play with a score’s rhythm.

While that’s one way to be musical, the versatile dancer needs other tools in their toolbox: The ability to dance slowly is just as valuable as dancing quickly, and while some choreographers look for a strong emotive connection to the music, others want dancers to ignore the score altogether.

Becoming a truly musical dancer requires developing a multifaceted relationship to music.

Start With Strength Training

Being able to move slowly with grace takes strength and control, so begin your musical training with physical training.

“You need a strong core,” says Peter Marshall, physical therapist at American Ballet Theatre. “That’s important for all movement, but especially the controlled movements of adagio.” Pilates mat exercises, yoga and balance training on BOSU balls or balance boards are all great for developing core strength. Marshall also suggests practicing développés to the front and side, aiming to hold your leg at the top for 3 to 5 seconds and then descending very slowly.

To train your body to be able to move quickly, focus on conditioning exercises that activate your fast-twitch muscle fibers—the type of muscular activation needed for the quick, powerful attack of petit allégro. Marshall recommends developing strong calves and ankles and suggests quick jumps on a Pilates jump board, lateral box jumps or dot drills (in which you jump rapidly on five floor spots) for building agility. Maintain correct form as you increase speed.

Play With Dynamics

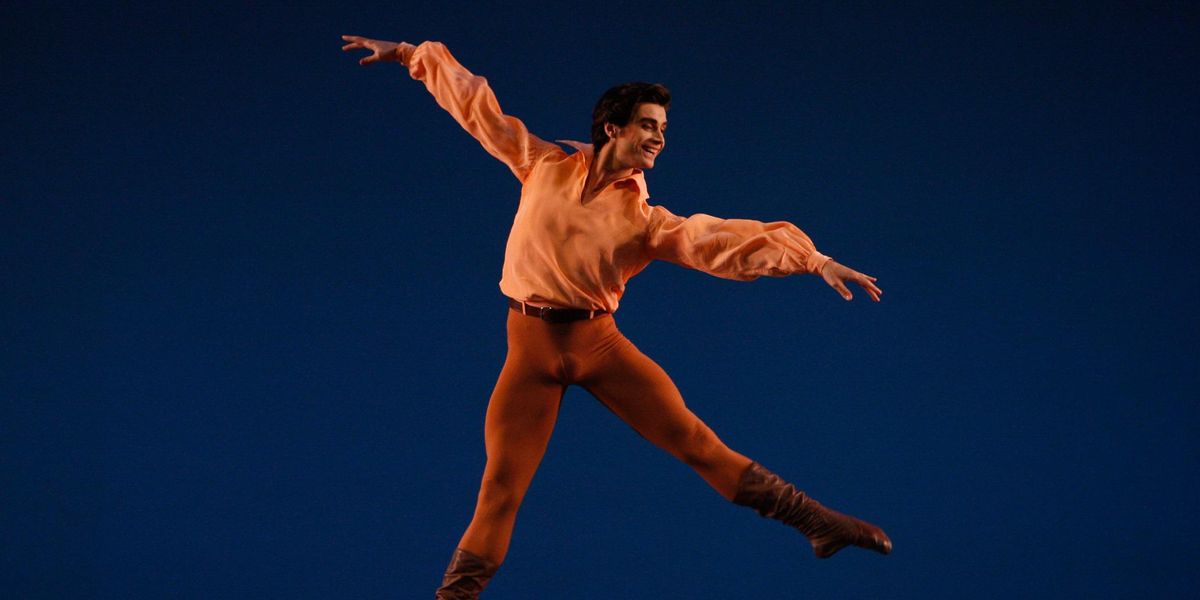

Slowness doesn’t have to be boring. “I often see students doing the correct steps in an exercise, but all done at the same level, so it looks bland and very monotone,” says former New York City Ballet soloist Antonio Carmena, who teaches ballet at Barnard College. “I’ll ask the students sometimes, ‘What do you want the audience to gasp for?’ ”

In fact, having a longer duration to execute slower movements can give dancers the opportunity to play with breathfulness, tension and timing. Experiment with different ways of anticipating or drawing out certain movements while still remaining within the correct counts.

Slowly Build Speed

Micah Sallid, a tap teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area, recommends starting slowly with clean, precise movements and then building up speed. “Day 1, I start with a basic four-count—just understanding how to count that and staying on tempo,” says Sallid. “We drill just tapping your feet to that four-count.” Once students are comfortable with that, she builds on it in both speed and complexity, adding accents and different kinds of syncopation.

Jen Philips Photography, courtesy Sallid

Mix Up Your Playlist

Having a versatile relationship to music is about more than just tempo. Embodying the melodies, harmonies, textures, accents and even silences in the music—through choices like your facial expressions and the quality of your movement—can enhance your performance.

Start by spending time listening to a variety of music. “Especially swing and jazz,” says Sallid. “Listen to Bach. Listen to Kendrick Lamar. Listen to My Chemical Romance.” Home in on the rhythms, harmonies and melodies. Notice the rises and falls in dynamics and the accents.

Practice Visualization

During your rehearsal process, try listening to the score and imagining yourself performing the movement a few times a day. You may find yourself more in tune with the music’s subtle cues when it comes time for a run-through. Or, develop your own imagery to help you connect with a score: One picture Carmena likes is getting on top of a wave as you turn. “If you get on top of the music, you’re riding the turn,” he says.

Move Against the Music

Being able to dance in contrast to the music is just as valuable a skill as synchronicity. You may find yourself dancing choreography that was created to music that isn’t

meant to affect your movement, or that is intended to be juxtaposed with the movement. A full-bodied explosion during a quiet note, or a minuscule twitch of an arm during a cacophonous climax, can evoke tension, emotion, anticipation or a dramatic shift.

Being able to hold your ground in your bodily quality despite hearing something starkly different in the accompaniment takes a firm understanding of the music. Start with the beat. “Counting is the only method for me,” says Carmena. “Musicians are always counting the music. As a dancer, you have to do the same.” Familiarize yourself with different musical landmarks—rhythm, melody, harmony—and gauge how the music makes you feel when you hear it. Is it lively? Does it seem to drag on ploddingly?

Once you understand the character of the music, practice moving against it. If you hear a steady downbeat, focus on the spaces in between the pulses, shifting between smooth and sharp motion. Alternatively, if a piece is atonal or non-melodic, try maintaining a steady pulse in your steps.

Ask the choreographer for specific descriptive words for the quality of movement they’re aiming for. Adjectives like “fluid,” “robotic,” “jittery” or “limp” can give you a physical focal point regardless of what you’re hearing in the score. If you find the music distracting, try a run-through in silence or with a different piece of music that evokes a similar quality as the choreography.

Teachers: For tips on developing musicality in your students, visit dance-teacher.com.