Is Dance Poised for a Union Boom?

Lots of dancers are union members—that isn’t new. Many of the country’s largest dance companies are unionized with the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), and dancers who work on Broadway are members of the Actors’ Equity Association. The Radio City Rockettes, Cirque du Soleil performers, and dancers at Disney and Universal theme parks are members of the American Guild of Variety Artists, and many other commercial dancers are members of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA).

However, there are parts of the dance world where labor-organizing efforts haven’t quite taken hold. While dancers at several operas and in two dozen or so ballet companies are AGMA members, only three contemporary dance companies are unionized: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Martha Graham Dance Company, and Ballet Hispánico. An ever-increasing number of dancers are freelancers, meaning they don’t have access to the traditional union organizing route. And many dancers still do nonunion work in theater, film, television, and concert tours.

Across all industries, union membership has been declining for decades. But the country seems to be in the midst of a shift: Since 2009, the number of Americans who say they approve of unions and want them to be more powerful has steadily grown. In 2022, the National Labor Relations Board reported a 53 percent increase in union election petitions over the year before, meaning that more Americans were joining together with their co-workers to try to form unions. The agency also estimates that a whopping 60 million workers wanted to join a union that year but couldn’t.

Is this pro-union boom also headed for the dance world? It might be—and it could bring some welcome changes.

Why Dancers Are Getting More Interested in Unions

Over the last few years, workers at many well-known companies, including Starbucks and Amazon, have undertaken high-profile unionization campaigns. Then there were the 2023 Hollywood strikes, where workers from SAG-AFTRA and the Writers Guild of America stood up to powerful film and television studios. Many experts have speculated that these high-profile labor actions might be fueling the increase in pro-union sentiment.

However, according to dancer Antuan Byers, who serves as dancers vice president on the AGMA Board of Governors, the breaking point for a lot of the people in the dance world seems to have been the pandemic. “Dancers felt so unprotected in a field that was already unprotected,” he says. “We felt horrible in that moment. And I think that a lot of us were looking around for an answer and we saw the unions step up to protect dancers.” Unions not only helped to establish COVID-19 safety rules, but also tried to insulate dancers from institutional budget cuts.

Lots of budding dance labor organizers are also driven by issues of equity and social justice. Research shows that unions help to dramatically reduce gender and racial disparities in pay, among other benefits for workers. “Esther,” a dancer at a midsize regional ballet company that unionized with AGMA last year, says the effort was spurred in part by the dancers’ discovery that male company members were making more than twice what similarly experienced women were paid. (Esther’s name has been changed because her company is still in the midst of bargaining for its first contract, and she fears retaliation.)

All of these influences seem to be producing a notable generational shift, according to Griff Braun, AGMA’s national organizing director. “In years past, generally speaking, it would be the younger dancers who were much more afraid of rocking the boat and of unionizing than the more veteran dancers,” he says. Not so much anymore. “Now, sometimes it’s the veteran dancers that are comfortable in their position and they don’t want to rock the boat. But the younger ones are like, ‘Hey, we’re just coming into this profession and it needs to be better,’ ” says Braun.

Where Are the Contemporary Dance Unions?

Over the last several years, a wave of smaller ballet companies have joined AGMA. But while both Braun and Byers say they’re occasionally approached by contemporary dancers who are interested in unionizing, no such wave has materialized on the contemporary side of the dance world. Why is that?

For one thing, says Byers, the union model is familiar to ballet dancers. Seeing ballet companies join AGMA’s ranks showed dancers at similarly sized companies that they could do it, too, adds Braun. Contemporary dance companies, on the other hand, tend to be much smaller than ballet companies, with, on average, fewer dancers, fewer administrative staff, and a smaller budget. Contemporary dancers are also more likely to be freelancers, and under current labor law, freelancers typically cannot form and join unions. A bill that would have changed this, the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, has passed twice in the House of Representatives, but has yet to make it to a vote in the Senate.

A common myth that employers use to try to discourage dancers from unionizing is that it will bankrupt the company. This isn’t true, Braun explains, because once the dancers’ union is formed with AGMA, it kicks off a negotiation with the company. A company can’t suddenly be forced to pay more than it can afford. But it is true that the union organizing and bargaining processes can be more difficult with a very small group of dancers because of several factors, including the fear of individual retaliation. It can also be intimidating and awkward, notes Byers, for dancers to have to deal directly with their choreographer or director, rather than having more administrative staff as a buffer.

But lack of budget shouldn’t necessarily discourage dancers from trying to organize. Even if substantial pay increases aren’t on the table, there’s so much more that dancers can bargain for. For example, “Laura,” a dancer at another midsize ballet company also in the process of bargaining for its first contract, and whose name has also been changed, said her union is pushing to receive casting and rehearsal schedules in a timelier fashion, and to make sure there are processes in place to keep the floors they dance on in safe condition.

Finally, says Braun, a big obstacle to organizing in the contemporary dance space is the culture. Declining to name specific companies, he says that directors at some modern and contemporary dance companies have instilled a strong anti-union sentiment in their dancers, often from the moment they enter the company. This creates a culture of fear around organizing for change. But that doesn’t stop a trickle of dancers from these companies from approaching AGMA every year—so eventually, the generational shift may take hold there, as well.

The Future of Commercial Dance Work

Instead of bargaining with individual dance companies the way AGMA does, Actors’ Equity bargains with all Broadway presenters and SAG-AFTRA with all film and television producers. Historically, you get into Equity and SAG by booking a union gig, which can mean attending endless frustrating and unsuccessful cattle call auditions. In response to criticism that this model can be exclusionary, in 2021 Equity shifted to an open-access membership policy, allowing anyone with past theater credits to join. Still, joining Equity or SAG-AFTRA can feel like a gamble for many dancers—the dues are higher than in other unions, and once a dancer joins Equity, they can no longer take dance jobs at theaters that don’t have Equity contracts.

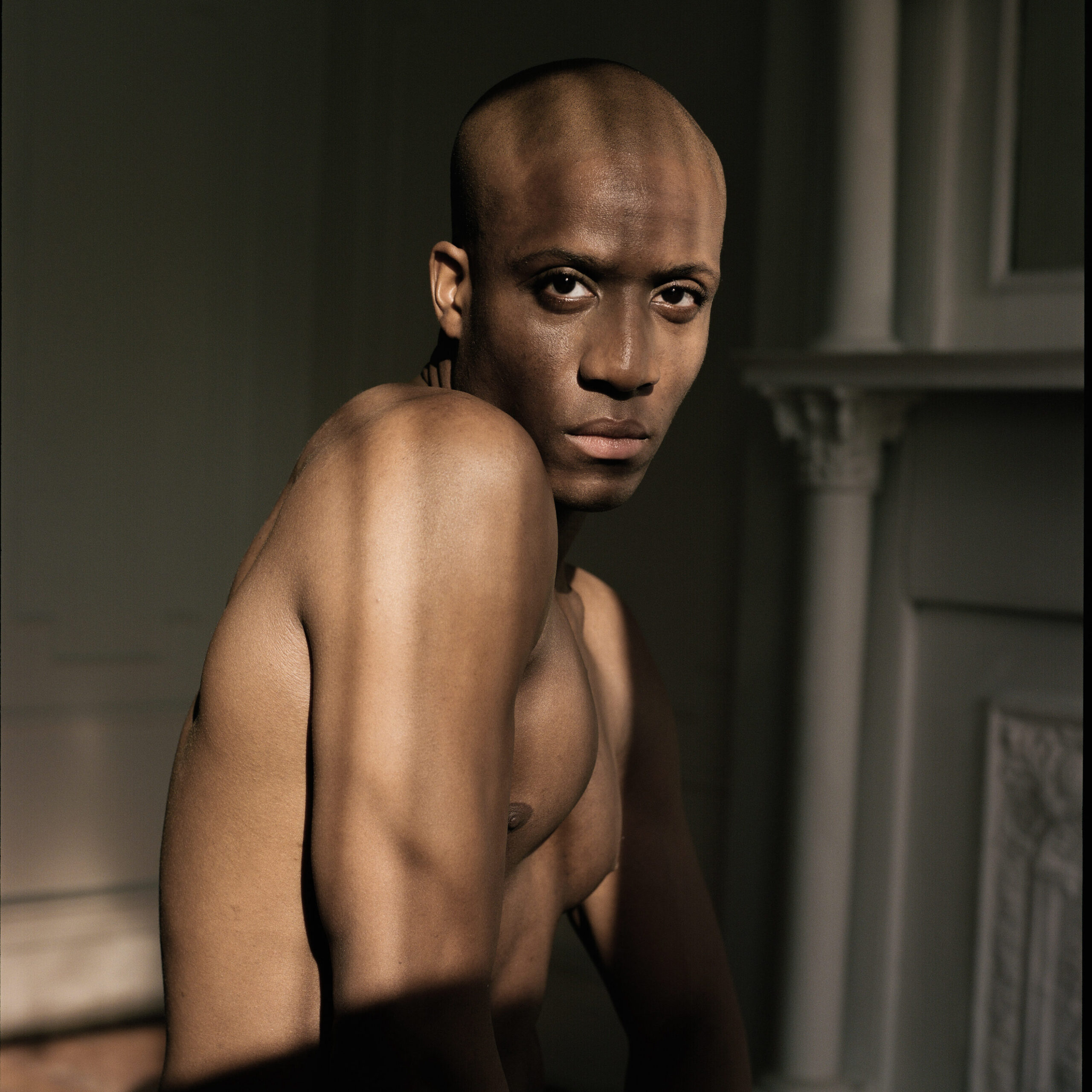

For Ehizoje Azeke, whose credits include Warner Bros.’ In the Heights, Netflix’s tick, tick…Boom!, and the HBO hit “Succession,” among many others, union membership is worth it. Nonunion gigs, he says, are a “Wild West.” He recalls one particular nonunion gig he did with Todrick Hall at WorldPride in 2019. At the last second, Hall and his dancers were invited to join Ciara for part of her set—but offered no additional pay. “There were 20 dancers on this project. Four of us said, ‘If you can’t pay us to do it, we’re not going to do it,’ ” he says. “But all 16 of the other dancers did that additional performance for a multimillion-dollar recording artist, for free.”

On a union gig, there would have been someone to call for help, and pay minimums for the additional work, among other protections. And the more dancers join a union and get accustomed to working under better conditions, the less likely they’ll be to accept substandard gigs. Thanks to the recent SAG-AFTRA strike, dancers will see some improvements in their work on film and television going forward. For example, they can no longer be paid less for rehearsal than for on-camera work. Azeke hopes that’s only the beginning as dancers get more engaged within the union.