How can Competitions and Conventions Become Inclusive Spaces for Transgender and Nonbinary Dancers?

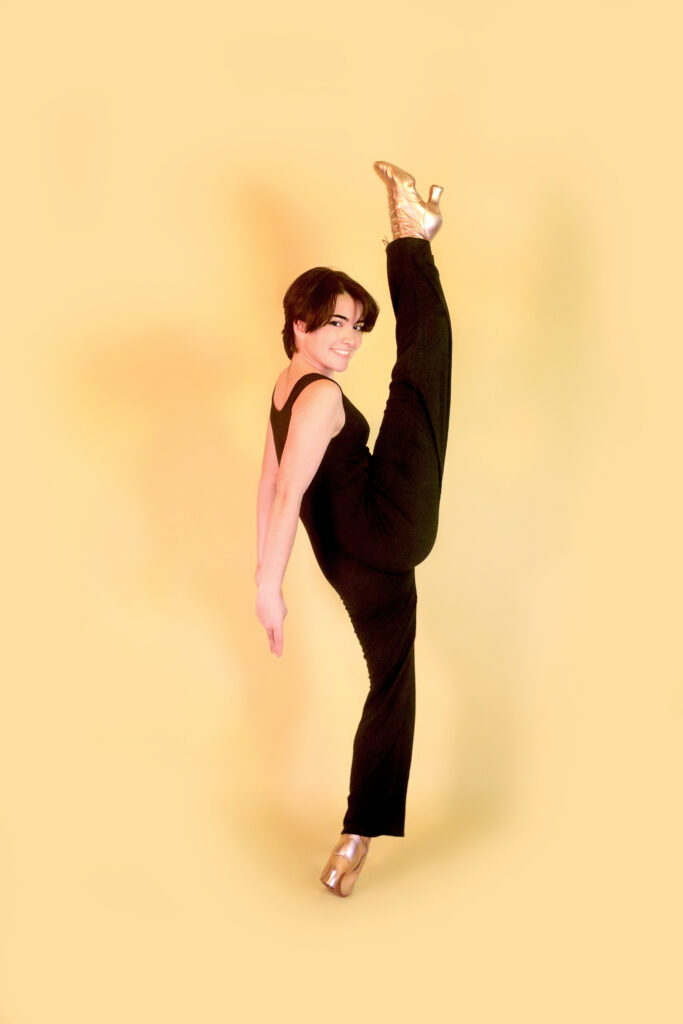

As a young student caught up in the whirlwind of the competition circuit, Micki Reynolds didn’t have many opportunities to think about gender. But by their sophomore year of high school, “I started questioning if I felt a different way about my gender identity,” they say. And they began to see competition stages in a new light. “I became more hyperaware of gendered categories and costumes,” Reynolds says.

By the time they were competing for title awards, something definitely felt off. “I remember not knowing whether the award fully represented me as a person or a dancer,” says Reynolds, who is nonbinary. “It didn’t feel right competing in a separate, female-gendered category. And it made me ask: Why are these gendered in the first place?”

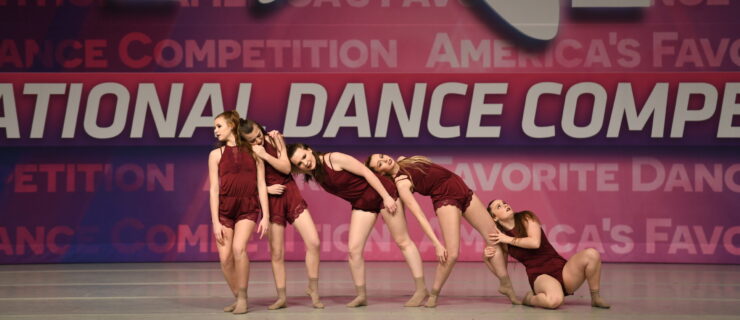

Winning the title of “Mr. or Miss [insert competition name here]” has long been considered the pinnacle of a competitive career. For decades, whether dancers actually identified with those gendered accolades—or the many other gender-based features of competition and convention weekends—was hardly ever questioned. Slowly, that’s beginning to change.

A Deep Divide

Transgender choreographer and educator Hayden J Frederick points out that a cisgender, heteronormative framework shapes nearly every aspect of the competition and convention world.

“Costumes, choreography, and concepts are all gendered,” Frederick says. In routines, girls and boys will come out to dance separately onstage. Partnering is almost always male/female. Convention teachers will call out boys to dance as a separate group, or gender movement by offering more “masculine” or “feminine” choreography options. And those are just the most obvious examples.

“Through all of this, queer or trans kids are made to feel like it’s inappropriate to speak about their experiences at all, when we’re literally allowing space for 6-year-olds to portray heteronormative love stories onstage,” Frederick says.

Making Spaces Safer

As discussions of safety and inclusivity at competitions and conventions mount, some directors have taken small but meaningful steps toward gender inclusivity.

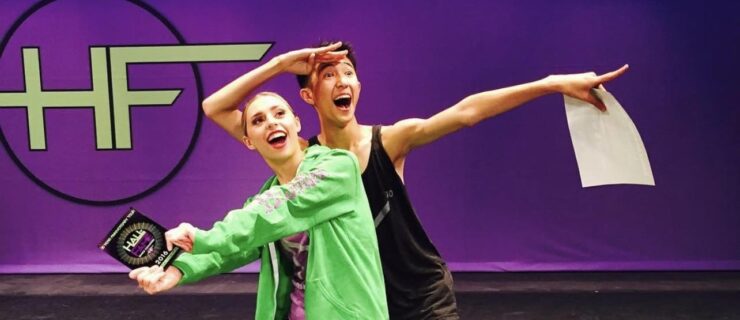

In 2020, Starquest introduced two gender-inclusive title awards: Emerging Artist and Elite Dancer. Similarly, New York City Dance Alliance has also opted to award two to three Outstanding Dancer titles per age category. Reynolds, who is an emcee at Turn It Up Dance Challenge, explains that these changes benefit all participants: “Often there’s only one boy up for a male title award. Gender-inclusive titles give everyone an equal chance to compete.”

As an emcee, Reynolds is careful to always address competitors with gender-neutral terms. Gender-inclusive dressing rooms have also become more ubiquitous, although they often have to be requested in advance by studio owners. And at HEAT Convention & Competition, stickers with preferred pronouns are available and encouraged.

Some organizations—like Embody Dance Conference, where Frederick is on faculty—have taken a comprehensive approach. At Embody, “all of the educators on board are committed to creating safe spaces in their classes,” Frederick says. The conference holds mindset and mental health classes tailored for dancers, parents, and studio owners. “We’re attempting to dismantle individual competitiveness and instead, with intersectionality as a framework, focus on community building,” Frederick says.

A New Normal

These changes are not always met with acceptance from customers and parents. “We sometimes get backlash that we’re talking too much about pronouns, or confusing the subject of gender with sexuality, which is totally not the case,” says Kobi Rozenfeld, co-owner and artistic director of HEAT. “But receiving one email from a parent about how our policies helped their kid feel more comfortable is worth dozens of negative emails.”

Unsurprisingly, the potential to lose out on sign-ups and profits is one of the largest perceived barriers to change. But Rozenfeld says the positives of gender-inclusive policies outweigh the losses. “I’m happy to be attracting clients that want to make a change in the industry,” he says.

Shaping a fully inclusive competitive world will take time, but the cause feels increasingly urgent. “As a country that’s in the middle of a mental health crisis and coming out of a pandemic that isolated our kids for a year,” Rozenfeld says, “we need to do whatever we can to make everyone feel accepted for who they are.”

Advice for Queer Competition and Convention Dancers on Navigating the Gender Binary

“Take up space. Do not change any part of yourself to adhere to restrictive standards and expectations. Please reach out when it feels too hard. There is community all around you, and we are here to hold you.”

—Hayden J Frederick

“Never be afraid to advocate for yourself. If something that a dance teacher or judge says makes you uncomfortable, vocalize it and correct them if you feel safe doing so. Little by little, society’s understanding of gender is changing, and we’re the generation that is making the change. Give yourself grace and be patient with the process.”

—Micki Reynolds