Remembering David Gordon (1936–2022)

The brash, witty, contrary, lovable David Gordon passed away on January 29, 2022, at age 85. A leading postmodern choreographer who crossed over into playwriting territory, he was massively prolific for about 60 years. He combined movement and words in ways that could be stimulating or jolting, focusing on family or fantasy, or delving into Ionesco, Shakespeare, or Aristophanes. Some of his iconic works, like the duets Chair and Close Up, are so simple as to be breathtaking. His larger works, like United States (1988–89), at Brooklyn Academy of Music and other locations, were multilayered, irony-drenched melodramas that could be wicked fun. A quick look at any page of his digital archive, Archiveography, reveals how fantastically ingenious his work was. I had the privilege of interviewing David several times for my book on Grand Union.

Gordon grew up in an immigrant Jewish family on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As a child he watched movies and vaudeville shows in neighborhood theaters. Fanny Brice’s singing “Second Hand Rose” and Milton Berle’s cross-dressing found their way into his early dance works. While at Brooklyn College, his Yiddish accent landed him in a remedial speech class. He studied visual art with top-notch artists and discovered that he enjoyed photography. After college he got a job dressing windows for the popular Azuma shop on University Place that sold items like kimonos and lanterns from Japan.

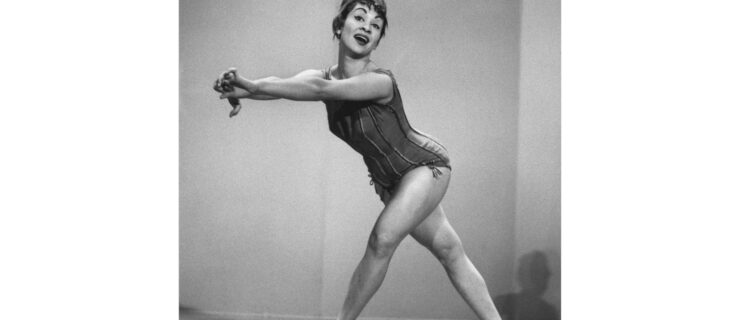

A chance encounter in 1957 with James Waring (1922–1975), a choreographer/designer with a ballet vocabulary, led to Gordon’s first sustained exposure to dance. In Waring’s studio he met Valda Setterfield, a tall dancer who had just escaped from the constrictions of the London ballet world. Waring put them together in duets, and their 60-year legendary dance partnership began. That same summer he studied with Merce Cunningham and Louis Horst at the Connecticut College Summer School of Dance (aka American Dance Festival).

Waring also introduced Gordon to John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg, told him to see W. C. Fields films and Kurt Schwitters’ collages and taught him about found objects, a concept Gordon deployed in his works. Although he was devoted to Waring’s composition classes, he also took Robert Dunn’s workshops at the Cunningham studio, which led to his becoming a founding member of Judson Dance Theater.

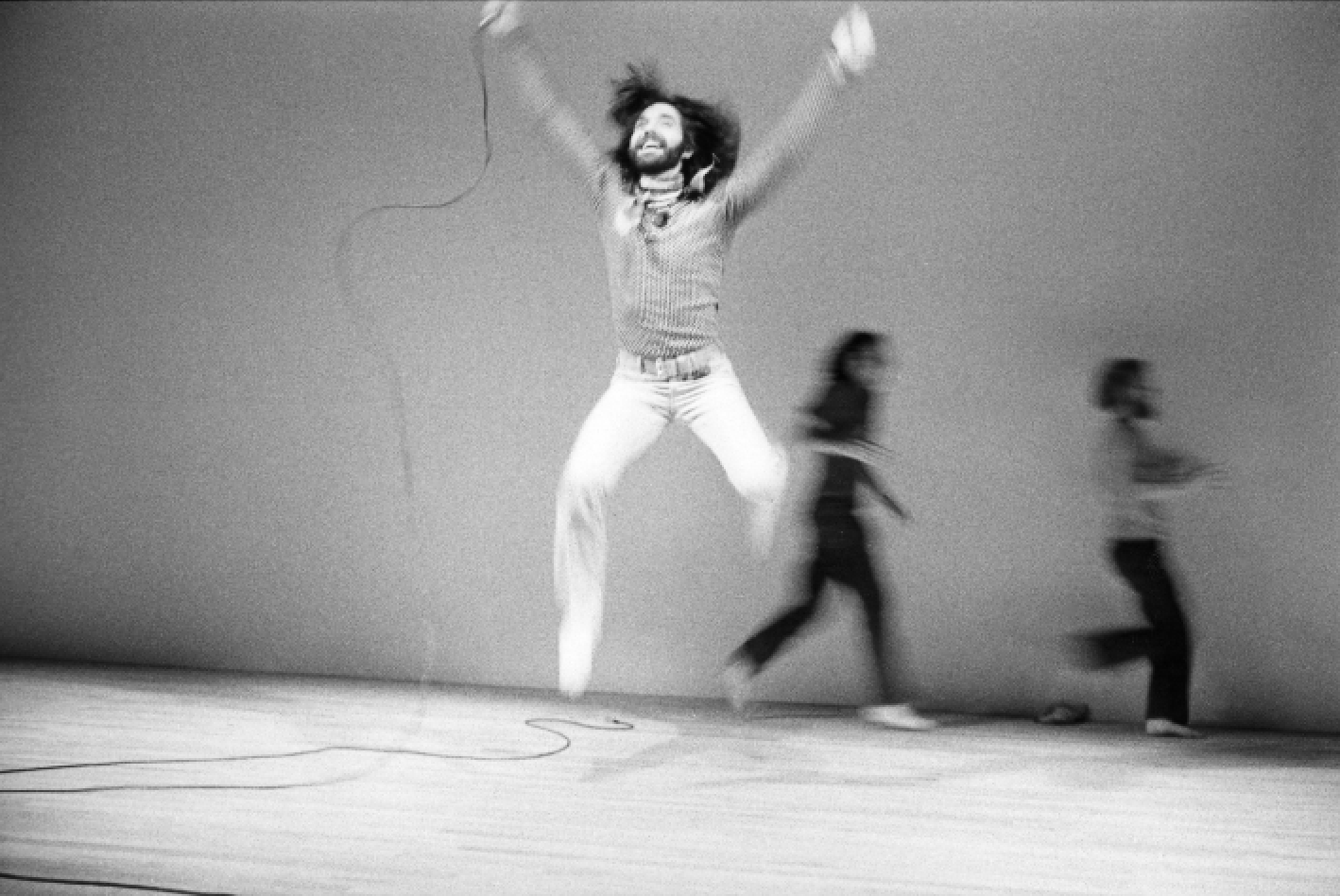

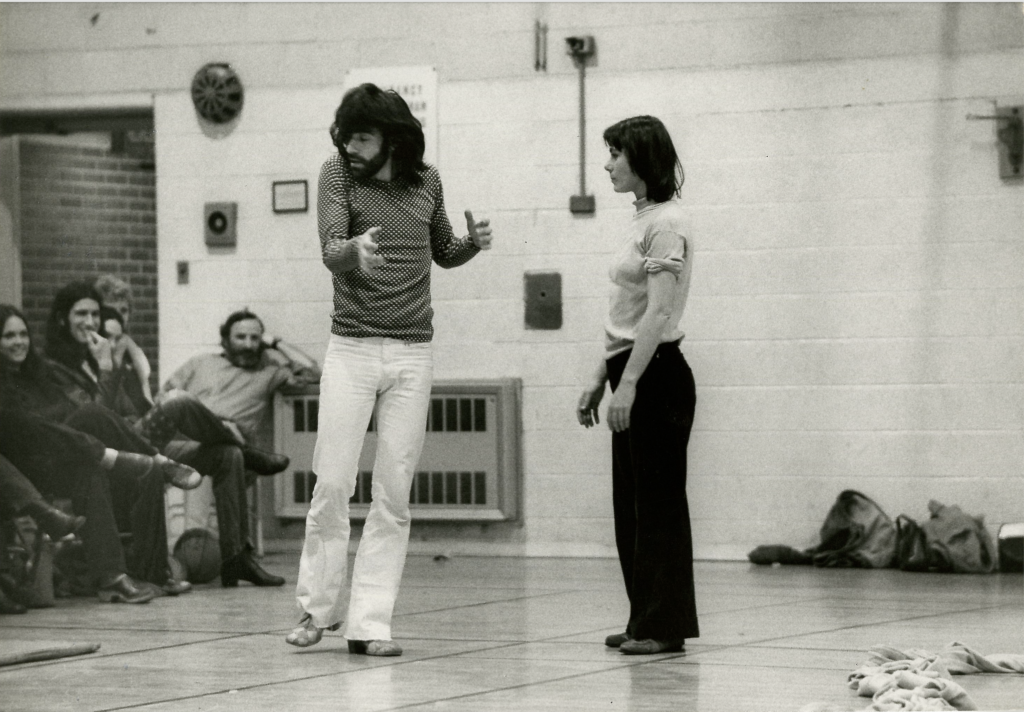

Gordon made several short works, often campy or outrageous, as part of Judson in the early 1960s. After performing his Walks and Digressions in 1966, he got so clobbered by a Village Voice reviewer that he vowed never to make a dance again. But he remained committed to dancing with Yvonne Rainer. When her 1970 work Continuous Project—Altered Daily morphed into a leaderless improvisation group, Gordon came along for the ride and even gave it its name, Grand Union, but he wasn’t at all sure about this improvisation thing. Within a few months, however, he became a master of dance-and-talking-or-singing improvisation, with more than a flourish of irony.

Grand Union gave him confidence, and he plunged back in to making dances—and plays—amassing a huge and varied oeuvre. Setterfield, who was in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, often graced his work as an elegant, timeless figure. Their legendary partnership lasted until his final days. In this podcast, Jed Wheeler, the director of Peak Performances, and Serious Fun before that, called them the Barrymores of postmodern dance, and the Fonteyn and Nureyev of performance. Together the couple, who had been married since 1961, received a Dance Magazine Award in 2019.

In this PillowVoices podcast that I moderated, Gordon described his mode of that period, both in Grand Union and in his own work: “It’s about being perverse. I want to do what you don’t expect me to do. I want to do what I don’t expect me to do. I also can’t tell if you’re having a good time unless I can make you laugh.”

But he could also make serious studies. In Chair (1974), he and Setterfield, each with a separate blue folding chair, quietly wrapped their bodies around, slid through the spaces of, and tipped till they fell off the chairs. They took task dance to new heights of inventiveness. Their two bodies entwining intimately with the two chairs translated as a telepathic intimacy with each other. This was a seminal work of postmodern dance.

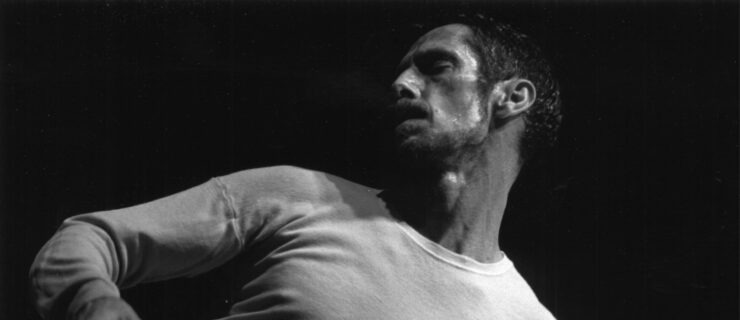

In the 1980s, Mikhail Baryshnikov, then the artistic director of American Ballet Theatre, asked Gordon to choreograph two works—quite daring considering Gordon’s position way outside the ballet world. Then in 2000, as founder of White Oak Dance Project, Baryshnikov asked him to direct his PastForward project, a celebration of Judson Dance Theater that toured extensively. Gordon contributed four works and wrote an introduction spoken on tape: “In the sixties, Russia put the first man in space; Trisha Brown walked on walls; Kennedy said ‘No’ to Russian missiles; Yvonne Rainer said ‘No’ to American dance conventions.”

In an interview with Pew Center for Arts & Heritage in Philadelphia, he said, “I take on projects I don’t know how to do, and I relish the dangerous journey.”

Although Gordon resisted the notion that he made “Jewish” work, scholar Rebecca Rossen includes him in her book Dancing Jewish: Jewish Identity in American Modern and Postmodern Dance. She discusses the production he directed and choreographed, Shlemiel the First, based on the play by Isaac Bashevis Singer and adapted by Robert Brustein, as well as his own The Family Business, with Setterfield, their son Ain and Gordon himself playing with characters modeled after his relatives.

David Gordon was a distinctly American choreographer. While his Judson colleagues Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs were more celebrated in Europe, he was supported consistently by American funders and presenters at home. When he made United States for Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival, he gathered citizen contributions from 26 presenters. The final production was a funny and full-bodied collage of scenes with a Keystone Kops theme threading through.

It’s impossible to count up how many works he created because he accumulated, recycled, reached back for every piece. Many of his works contained a nucleus of his earliest pieces, like Mannequin Dance, which he made at Judson, and The Matter, which he made as part of Grand Union’s residency at Oberlin College in 1972.

When it came time to archive his astonishing output, Gordon did it his own way. Instead of writing a book or making a documentary, he created a complex and endearing digital archive (with help from archivist Patsy Gay and others), juxtaposing photos, his personal memories and reviews, organized with the wit and visual distinction that mark all his work.

In the past decade, when he became less mobile, he crafted delightful digital collages with visual wordplay. These designs related to his enduring interest in framing, whether in photography, window dressing or the proscenium stage. As he said to me about these collages, “The computer is my enda life rectangle.”

He created two major virtual works during the pandemic: The Philadelphia Matter 1972/2020, an episodic accumulation for 30 dancers, each on their chosen turf of the city (see Gia Kourlas’s review in The New York Times here); and The New Adventures of Old David (What Happened 1978–2021), in which his dancers recycled Gordon’s greatest hits, newly framed, commissioned by Peak Performances, in Montclair, New Jersey.

Some of today’s dance artists were at one time involved in Gordon’s work, including Dean Moss, Wally Cardona, Cynthia Oliver, Jane Comfort, Christina Svane and Leslie Cuyjet.

He is survived by Setterfield, their son Ain and his husband (the choreographer Wally Cardona), his sister Lois Gitelson, six nieces and nephews, and two granddaughters.

For More on David Gordon:

David Gordon’s Archiveography

An internet archive of Gordon’s work, decade by decade

Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance

By Sally Banes

The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance, 1970–1971

By Wendy Perron

Dancing Jewish: Jewish Identity in American Modern and Postmodern Dance

By Rebecca Rossen

Dance Magazine Award Honorees: David Gordon & Valda Setterfield

By Susan Yung, Dance Magazine, December 2019

“The Talking Cure: David Gordon and Valda Setterfield”

Peak Performances

“Wendy Perron on Grand Union: Democracy or Anarchy?”

(with David Gordon’s voice)