How Dance Artists are Taking Inspiration From What They Eat

Novena is a joint project between choreographer Jay Carlon, composer Micaela Tobin and a somewhat unconventional third collaborator: rice. The work, which debuted in 2022, grapples with the nine stages of grief and reimagines the novena, a Catholic mourning prayer, through a queer, postcolonial lens that also draws on Carlon’s Filipinx heritage. According to Carlon (who uses he/they pronouns), rice plays a big role in Novena—and in their larger process as an artist. “Rice became something that I was really obsessed with as a resource in my work,” they say. “I grew up on rice, eating rice three times a day, and I just wanted to use rice within the role of cultural identity, sustenance, colonization—rice as canvas.”

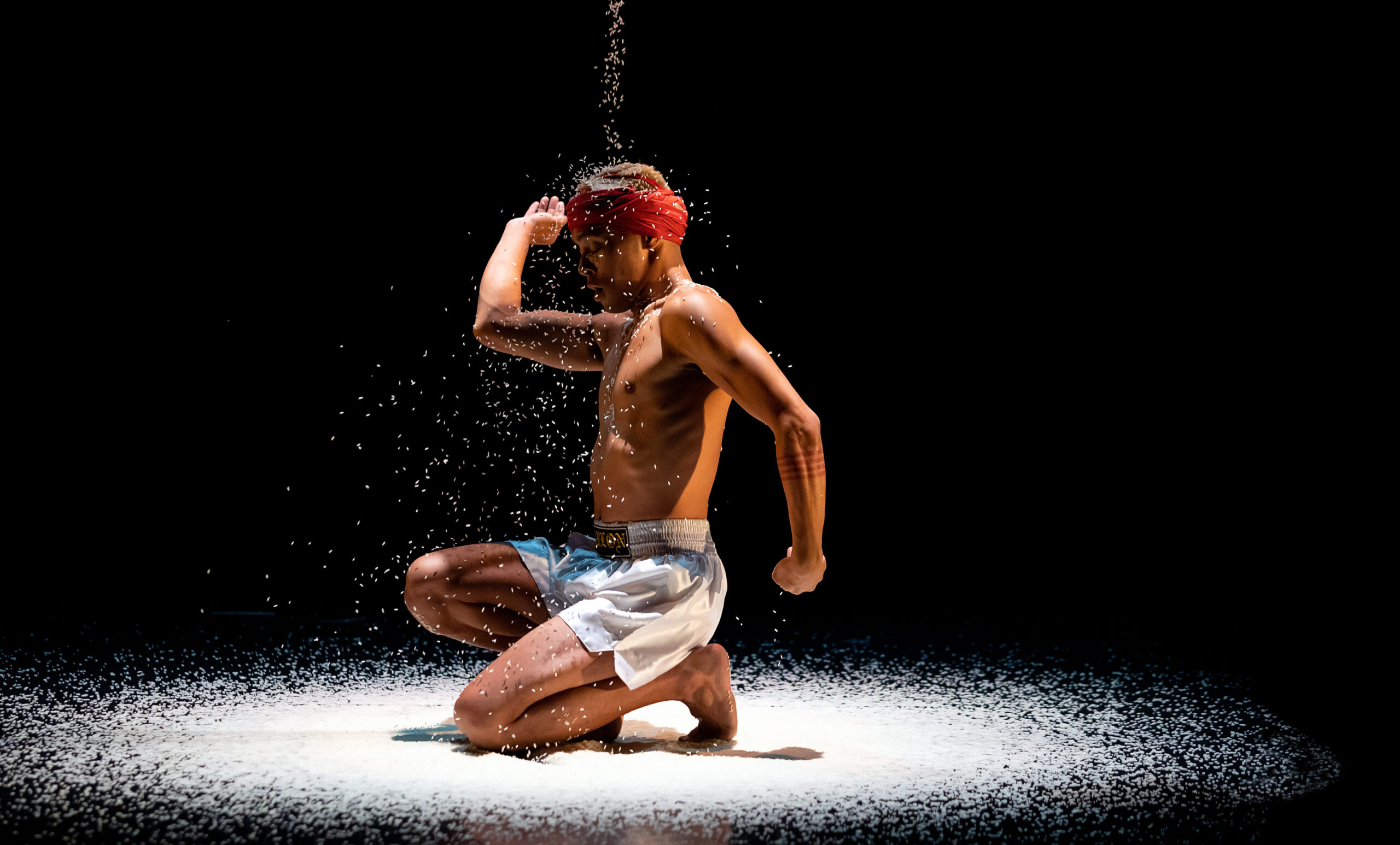

During the performance—which is part of a larger work, WAKE, set to premiere this year—Carlon carries a bag of rice around the stage and pours it into a punching bag, which he fights. Then, he cuts a hole in the punching bag and allows the rice to pour over his body. This duet, he says, allows him to “transmute a lot of the pain and suffering into acceptance and joy,” replacing, with rice, the rosary traditionally used in the ritual of the novena.

Food has played a role in Carlon’s work since 2020, when the pandemic prompted his deep reflection into what it would look like to decolonize performance. “I wanted to do that with feeding the audience,” he remembers. “If you ever go to a Filipino household, the first thing that they will make you do is eat, and if you don’t eat, it’s rude. So I was trying to infuse that into my practice.”

As Carlon has found through the projects he’s created since then—which include a food and cocktail event, plus several performances and artist talkbacks—the through lines between dance and food are plentiful. Carlon and other dance artists are using food not only as inspiration, but also as an avenue to explore themes around sustainability, identity, culture and heritage.

Fruitful Parallels

According to Meryl Rosofsky, a food scholar at New York University and the creator of the Breaking Bread with Balanchine project—which explored the choreographer’s life through his love of food and included a 2018 Works & Process event—there are both literal and metaphoric parallels between the art forms. She cites technique, timing and established rules as some of the more clear-cut similarities, while also emphasizing the expressive nature of each medium. “They both allow for and are enriched by improvisation and experimentation; they both might result in mistakes or even failure, but also the possibility of actual transcendence,” she says. “And, I think that both are connected to the drive to give others pleasure and nourishment—cultural, spiritual, interpersonal sustenance.”

These connections are something Eliana Trenam, a dancer with Portland Ballet, has experienced firsthand. Trenam, who has worked in a variety of fine-dining restaurants and is an active hobbyist chef, says that dance and food have overlap both in their ephemeral nature and in the way they can render the ordinary extraordinary. “If you were to come back and order the same thing, it would be slightly different each night,” she explains. “Just like if you were to go see a performance, no two experiences are going to be identical, and that’s what makes it alive and engaging.”

Rosofsky believes that both dance and food have the unique capacity to show others—and ourselves—what it is that makes us who we are. “Food tells our stories. I think that’s it in a nutshell,” she says. “Food and cooking, they both define us and encapsulate so much of our ancestral heritage and our personal biographies, as well as the contemporary world around us.”

Illuminating Culture and Process

Many dance artists are harnessing these parallels—and the windows into self they provide—to connect with their own cultures and familial heritage, and to understand others’ ancestry. Dancers Unlimited, a company based in New York City and Hawaii, started the development process of its most recent work, Edible Tales, through conversations about the foods each dancer had grown up with and the memories surrounding these meals. The company also harnessed connections with Hawaiian elders practicing traditional and sustainable methods of farming taro, a sacred Hawaiian food, as they created Edible Tales.

“We were able to actually get into the farm, thigh-deep into the taro,” Linda Kuo, the co-founder and director of Dancers Unlimited, says. “It was an experience, if you’re not used to it—being in the mud, taking care of the taro and really reflecting on the relationship of what the taro represents for the native Hawaiians, what it means for us as settlers to be a part of this environment, and how we’re all interconnected.”

During one section of Edible Tales, a dancer pounds taro onstage, creating a rhythm to which the other dancers move. The work also involves an altar with food from each dancer’s family and an immersive installation that allows audience members to plant seeds.

“Dance and food automatically give you a window into someone’s culture,” says Candice Taylor, the co-artistic director of Edible Tales, adding, “for me using food really gave me another tool to access my ancestors and to learn about different cultures.”

Carlon, too, has used their artistic process to connect with roots—both their own and those of their food. In December 2022, the choreographer traveled to their hometown in the Philippines and visited their uncle’s rice farm to learn to plant the crop. “I wanted to get my hands and my feet into the soil, and I was able to do that in my hometown, where my family is from,” they say. “Generations of this type of cultivation, and I was able to finally engage in that.”

After Carlon’s rice was harvested in March, his uncle saved him a bag, and the artist hopes to use it as part of “some type of ritual engagement,” such as a meal with his mother or using the rice in a performance.

A Vessel for Social Justice

In addition to using dance and food to delve into the self, artists are also using it to explore issues of sustainability, lack of access, loss of native lands and other social justice topics. Ananya Chatterjea, founding artistic director of Ananya Dance Theatre, first considered exploring themes of food and nourishment in her work in 2006, when she spoke with Indian farmers about the unpredictable nature of the monsoon season on which they had previously relied.

“That sort of clued me into this notion of how what we do in big industry caused these shifts that actually endanger us,” she remembers. “I started thinking about these concepts of food deserts, how so many children do not know where their food comes from because they’ve not been taught.”

Those conversations also inspired Chatterjea to create a trilogy of works related to environmental justice, and she expanded on themes surrounding food more specifically in her 2015 work, Roktim: Nurture Incarnadine and her 2012 work, Moreechika: Season of Mirage.

Kuo and Taylor, too, say that after exploring their memories related to food and its connection to ancestry and culture, they also delved into food-adjacent social justice topics. “It’s through conversations about immigration, assimilation, the loss of connection to cultural food, or the loss of land, in the case of native Hawaiians, to grow even their ancestral food,” Kuo explains. “The conversation shifted from comfort food towards social justice and cultural heritage.”

Taking inspiration from food can not only provide an apt medium for exploring such topics, it can also make a big difference in the lives of the dancers themselves, says Chatterjea. Through their choreographic investigations of food, Chatterjea and her company members considered “the ways in which women and femmes across the globe work with seeds and food as a way to nurture and hold dear their communities.” What they learned from the investigation became a large part of their company culture. “Dancers’ relationship with food is complicated. Food denial is something that is actually glorified in some ways for dancers,” Chatterjea says. “We are quite the opposite of that. Because of these practices of thinking of food as nurture, and that which has grown from the ground as nurture, the relationship with food within the company is very different.”