Indiana University Removes Offensive Caricatures in New Productions of The Nutcracker and La Bayadère

How can we honor and preserve history without repeating the same mistakes over and over? How can we reimagine classics to center a variety of voices and speak to diverse audiences—not simply to avoid offending anyone, but to actively invite and include everyone? How can we propel the dances we know into a new era, so they—and ballet—can flourish into the future?

These are some of the questions of the moment in the ballet program at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, which is staging new productions of The Nutcracker and La Bayadère this school year. Both ballets have come under fire for resorting to reductive, Orientalist caricatures—with La Bayadère all but disappearing in its full-length form from American stages.

There’s a perceived “zero-sum game, where it feels like we either respect the heritage and the canon and the tradition, or we respect the experience of people of color,” says Phil Chan, co-founder of Final Bow for Yellowface. “Both of those things can happen at the same time.” Chan, who has long advocated for eliminating outdated and offensive Asian stereotypes from ballets, will stage the reimagined Bayadère in Bloomington with dance historian and musicologist Doug Fullington. “It is through this process that the work can remain alive and radical and relevant,” adds Chan.

That concept resonated deeply with Sarah Wroth, a professor and chair of the ballet department at IU. It couldn’t be more fitting for these projects to find a home at an academic institution, Wroth says, that sits at the intersection of scholarship and stage and has the time and resources to experiment. And the new productions offer an educational opportunity that students are thirsting for. “Young dancers today know what they want to be doing with their art form,” says Wroth. “They know what they want it to be creating in society. And I think it’s hard for them if they don’t get to see and feel that progress.”

A New Nutcracker

When Wroth returned to her alma mater as an educator after a 14-year career with Boston Ballet, the department was still using the same Nutcracker sets and costumes she remembered from the early aughts. The faculty decided their Nut needed a revamp—and that their colleague Sasha Janes was the choreographer for the job.

Janes’ vision bridges the acts so that they feel like one whole rather than two separate ballets, as is often the case in The Nutcracker. The Act I Christmas party is set in an embassy. The guests are delegates from various countries, wearing traditional dress and bearing gifts from home. “Rather than seeing this Victorian thing where all the men are in brown suits and women are in the same dress but different colors, I think we see individuals,” Janes says. “Because that’s the world we live in, right?”

Drosselmeyer—who in Janes’ production is a woman—helps stir Marie’s imagination. The rest of the ballet brings back characters from the party. The severe butler becomes the Mouse King. The ambassadors from Norway become the Snow King and Queen. Mother Ginger brings her charges from the local orphanage. The Chinese divertissement eschews upturned fingers and racist makeup and becomes a dance revolving around the delegates’ gift of silk.

This Nutcracker also uses technology, combining physical sets with projections, to transport its audiences and push the ballet forward. “Nutcracker is our one stronghold on American tradition,” Wroth says. “We just need to keep making choices for the betterment of it.”

A Better Bayadère

As soon as The Nutcracker wraps, IU students will dive into Bayadère rehearsals. Chan mentioned his and Fullington’s concept—which has been brewing for at least five years—when he gave a lockdown-era Zoom talk for the department. Wroth jumped on it: Could they bring that Bayadère to life at IU?

“My favorite creative prompt is asking myself the question: ‘What else could it be?’ ” Chan says. “Like when you’re a little kid and you have a pen, but it’s not just a pen. It could be a rocket ship or a lightsaber or magic wand. How can we apply that kind of thinking to a work like Bayadère?”

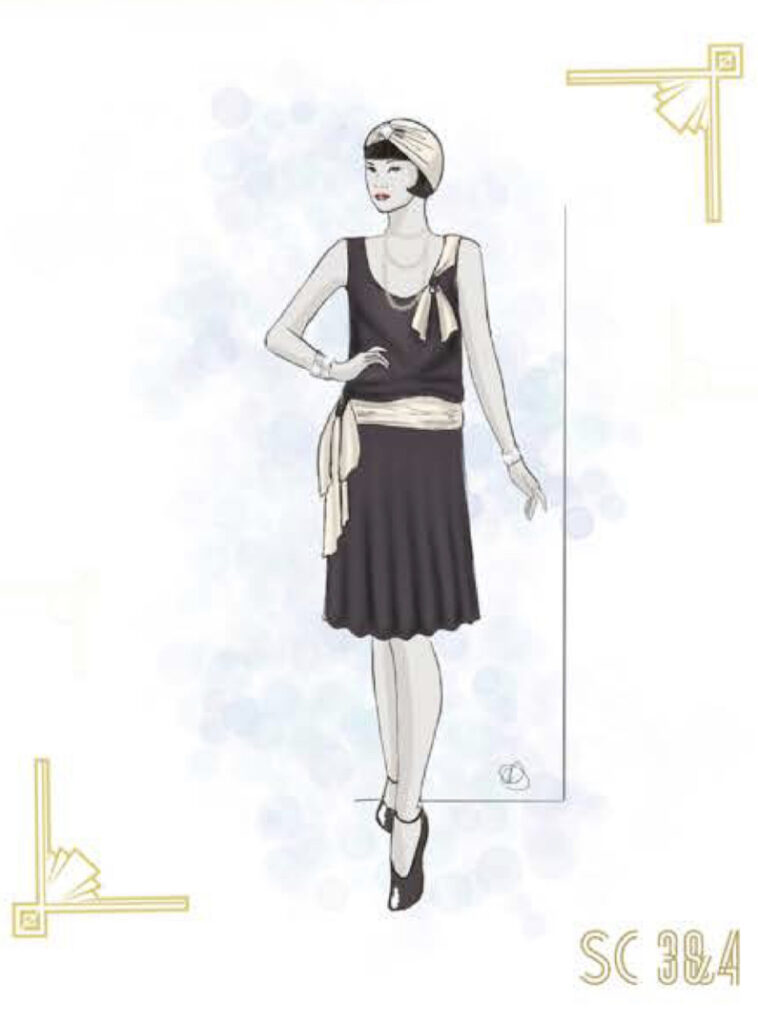

Instead of reproducing a French-born, St. Petersburg-based ballet master’s imagined India, Chan and Fullington are setting their love triangle during the golden age of Hollywood. Though they’ll re-create much of Marius Petipa’s choreography based on notations from 1900, the tale is reminiscent of quintessential American musicals like Singin’ in the Rain, Chan says, “if Nikiya was like Debbie Reynolds and Solor was Gene Kelly, and Lina Lamont, the sort-of princess, was this Gamzatti character.” In this telling, Ludwig Minkus’ score is reorchestrated in the style of a Gershwin musical, the Golden Idol is a dancing Oscar statue, and the iconic Kingdom of the Shades becomes an Art Deco fantasy à la Busby Berkeley.

“With the flip in the storyline, the beauty of the dance remains and the questionable plot dissolves,” says senior Ruth Connelly. Fellow senior Aram Hengen adds that IU’s learning environment is the perfect place for this change to begin: “It’s a lab, basically.” Both are excited to see ripple effects beyond their campus.

Chan, Wroth, and their colleagues are too. “All I’m saying is, ‘Let me show you just one other way to do it,’ ” Chan says. “Everybody benefits if we get more Bayadères. That’s the beauty of this form. It can take reimaginings.” The stories we tell have to reflect us, even when it comes to the classics, Chan says, and the stakes are high: “We’ve got to figure out a new way to do that for this new, more diverse, younger generation—or else we are doomed.”