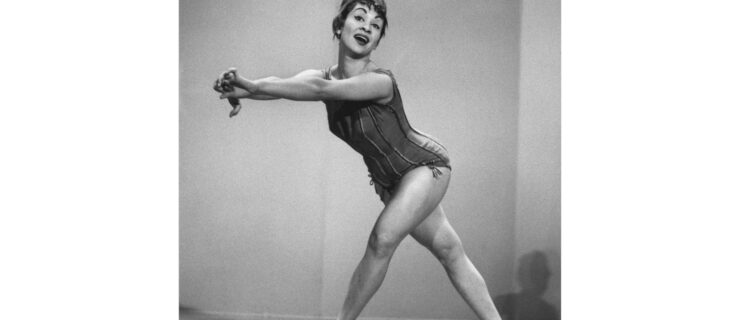

Remembering Annabelle Gamson, 1928–2023

Dancer and choreographer Annabelle Gamson—whose versions of solos by Isadora Duncan changed the way a generation looked at Duncan’s work and thought about her as a choreographer—died five days shy of her 95th birthday, on August 1, 2023, in Newport Beach, California.

Although, since Duncan’s death in 1927, several generations of Duncan dancers had performed in Europe and Russia, as well as in the U.S., Gamson’s 1974 New York program of solos made the latter’s art seem to burst forth newly born. Her subsequent Manhattan concerts—at Dance Theater Workshop (now New York Live Arts) and at Carnegie Hall, accompanied by the concert pianist Garrick Ohlsson—presented indelible images of her: a Valkyrie with thick white hair, penetrating gaze, bare feet as sensitive as hands, and an ageless body enrobed in flying silks.

Gamson rigorously studied historic solos by Duncan, Mary Wigman, and Eleanor King, which some audiences thought were improvised, and offered them as intentional and repeatable choreography. She emphasized their reliable coordinations of movement with music; their presentation of space as a tangible habitation; and their theme-and-variations patterns of gesture, suggesting a moment-by-moment projection of a commanding psychic intelligence.

Observers of Isadora Duncan—and Duncan’s own statements—do not agree that Duncan danced quite this way. However, the moral sobriety of Gamson’s performances left the decided impression that Duncan’s dances in their Platonic form were spiritual architecture of rare artistry. Cultivating an awareness of the gravitational forces within those solos was also the subject of Gamson’s coaching sessions with other dancers. One of her protégées, the choreographer Janis Brenner, articulated Gamson’s coaching from the inside:

Annabelle was an exacting and demanding coach and mentor who was so inside the gestalt of the dances that one could not help being absorbed into her orbit while working together. My personal revelation was musical: I came directly to Annabelle from dancing with Murray Louis for many years. Murray was also a very ‘musical’ choreographer. But what we did with Murray was jump on top of the music and ride it—we were to be in charge of the music. What I did with Annabelle was in a way the opposite—the music pulled us into the movement, drew us forward to attenuate, to relish movement’s oppositional forces. This investigation and difference added profoundly to my dancing and influenced my choreography.

As chronicled in the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, Annabelle Gold, a daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, was born in the Bronx on August 6, 1928. As a child she studied Duncan dancing with Julia Levien, a former member of the troupes of Duncan’s adopted daughters Anna and Irma, before attending the High School of Music and Art and later the Professional Children’s School. She also trained with a variety of other distinguished teachers, including at the school of Katherine Dunham, with whom Gold performed at Café Society.

Between 1950 and 1961 alone, she studied in Paris with Étienne Decroux, the innovator of modern pantomime; performed with Anna Sokolow on Broadway and television; danced the Cowgirl in Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo with American Ballet Theatre; and married the musician Arnold Gamson, returning with him to Europe to direct operas. For some years she left performing to rear their children, Rosanna (now a choreographer) and David (a musician/composer), who survive her. By the mid-1990s, Gamson had left dance to paint.

In a 1981 interview with Lee Edward Stern, she said of her longstanding engagement with Isadora Duncan: “It was purely a selfish interest. I loved the work. … [In the Duncan solos,] I really am just being myself, as any actor would be.” She added of Duncan’s dancemaking, “It’s technically very subtle. It’s simple but not easy.”