Stuart Hodes, a Force in the Graham World and Beyond, Dies at 98

Watching Stuart Hodes dance, learning from him, or just hanging out with him, one felt a tidal wave of enthusiasm. He was a force in the Martha Graham Dance Company for years, as both a performer and teacher. He also danced in Broadway musicals and on television, choreographed a slew of works himself, and was a freelance performer with downtown choreographers. As an educator he was purposeful, as an administrator he was inspired. A multifaceted citizen of the New York dance world, he was beloved by colleagues and students across the dance ecology. The Lifetime Achievement Award he received from the Martha Hill Dance Fund in 2019 was well deserved and joyously applauded.

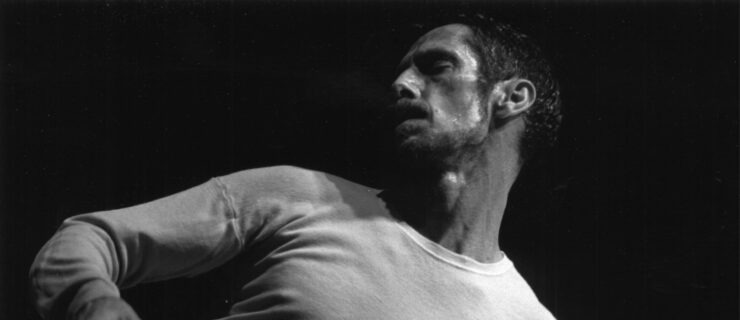

Born in 1924 in New York City, Stuart Hodes Gescheidt attended Brooklyn Technical High School. He played violin in the school orchestra and joined the swim team. On his 18th birthday, in the midst of World War II, he was drafted and trained as a B-17 bomber pilot. He also got some writing practice with an army publication and later for a drama organization in Vermont. Hodes flew into the Graham orbit at the end of the war, joining her company four months after he took his first class. His robust presence graced her ballets from 1947 to 1958. You can see him as the Husbandman, bursting with optimism, in Appalachian Spring in this 1959 film.

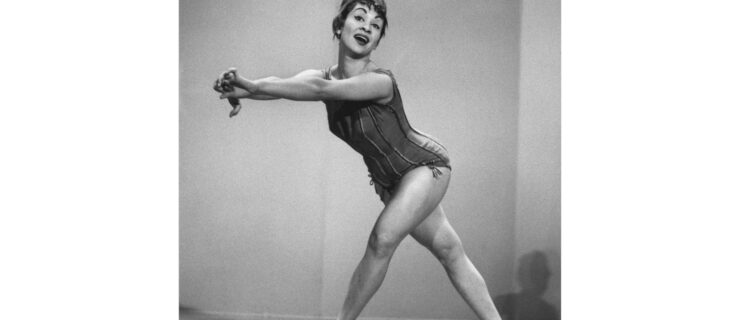

He married Linda Margolies (Hodes), a dancer who also became a pillar of the Graham establishment, in 1953, and they had two daughters. He spoke warmly about family life. But they divorced 10 years later, and he married Elizabeth Wullen in 1965.

Hodes’ recent book, Onstage With Martha Graham, tracks his tumultuous relationship with Graham, his visceral joy in the technique, and the ups and downs of the many tours and performances. He offers insights about both Martha the woman and Graham the artist. He paints a picture of her as needy—needing to banish him and needing to beg him to come back time and again. “ ‘Martha’s genius,’ he writes ‘lies in being able to reveal the glory and catastrophe of being human.’ ” The book is a treasure chest of insights, inspiring me to collect “13 Gems From Stuart Hodes’ New Book on Martha Graham.”

In an article in The New York Times in 2007, Gia Kourlas quotes Hodes saying, “I wanted to be around Martha all I could, except when I couldn’t stand her.” At an occasion commemorating Graham in 2015, he confessed: “The only way I equal Martha Graham [was that] I have as big a temper.”

During the Graham company’s off seasons, he found gigs in Broadway musicals. The choreographers he worked with include Agnes de Mille, Jerome Robbins, Jack Cole and Donald Saddler, whom he sometimes assisted. “The things that happen backstage—they are mind-boggling. I find stories of flops the most fascinating of all,” he said on a panel sponsored by Dancers Over 40, “because they all start with a dream.” He was so keen on dancers’ stories that he started a short-lived website called ChorusGypsy.com. His first memoir, Part Real, Part Dream: Dancing with Martha Graham, was published in 2011.

He often compared the thrill of dancing with the thrill of flying a plane alone. Recalling his seven combat missions in this PBS segment, he says: “The plane became an extension of my body […] I felt that dancing and flying were two ways of getting to the same state […] I think anything you do with every particle of yourself can be wonderful, and it can make you forget the world. It’s magic.”

He held a string of leadership positions, including at New York University’s School of the Arts (before it was called Tisch), the interdisciplinary Kitchen Center (he oversaw its move from SoHo to Chelsea), the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance (as it struggled to restart around 2000), and the Dance Notation Bureau. When the Graham legacy was put in jeopardy by her nondancer heir Ron Protas, Hodes testified in court to defend the company’s right to perform her works. His written account of the long, fraught trial, Graham Vs. Graham: The Struggle for an American Legacy, is available in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts as is his interview for the Jerome Robbins Dance Division Oral History Project.

In the 1980s, he came back to perform for younger choreographers, including Stephan Koplowitz, Claire Porter and Gus Solomons jr. Reached by phone, Koplowitz, who made three dance-theater pieces on Hodes, said, “There was a combination of gravitas and lightness and realness in his presence. He was a dancer and an actor. He had a way of making anything he said onstage real. He was a natural storyteller. Rehearsals took longer because he liked to tell stories.”

Hodes choreographed for many companies, including Boston Ballet, Harkness Ballet, Joffrey Ballet, San Francisco Ballet, and for his own youth group, The Ballet Team. From 1992 to 1996 he and Elizabeth Hodes toured locally in musical/dance duets like Dancing on Air with Fred Astaire and The Sound of Wings, about Amelia Earhart. His utterly delightful duet I Thought You Were Dead, co-created with the late Alice Teirstein, was named one of the year’s 10 best dances of 1996 by the publication Ballet Review.

He could be wickedly funny, too. In the 2007 production of “From the Horse’s Mouth,” which that year was a tribute to Martha Graham, Stuart recited his clever “Martha Rap.” In my memory, one of the lines was about how Ruth St. Denis thought Martha was ugly, but Ted Shawn wanted a partner less pretty than himself.

Hodes’ earlier book, A Map of Making Dances (1998), overflows with various approaches to choreographing. It’s in the form of 247 numbered “projects,” pulled from his vast experience of dancing, choreographing, teaching, observing. Some of these seeds of creativity are conventional assignments and others can turn you inside out, like “Reinvent the joints in your body” or “Use music you dislike.” This book also pays tribute to fellow dance artists who have influenced him, including Remy Charlip and Robert Dunn, by bringing some of their unorthodox ideas into his fold.

Hodes was deeply committed to dance education. Author and educator Ellen Graff partnered with him on many educational projects. She had known him in the Graham company in the ’50s and also worked with him in recent years with Dances for a Variable Population. “His enthusiasm embraced all different aspects of the field,” she says. “He was so supportive toward other dancers and teachers. And he had an eye for talent. When he was the head of dance at NYU, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker was a student there and he told me he knew right away that she was going to be a player in the field.”

Thank you, Stuart, for the insights and joy you brought to the dance world.