Modern Dance Legend Yuriko Dies at Age 102

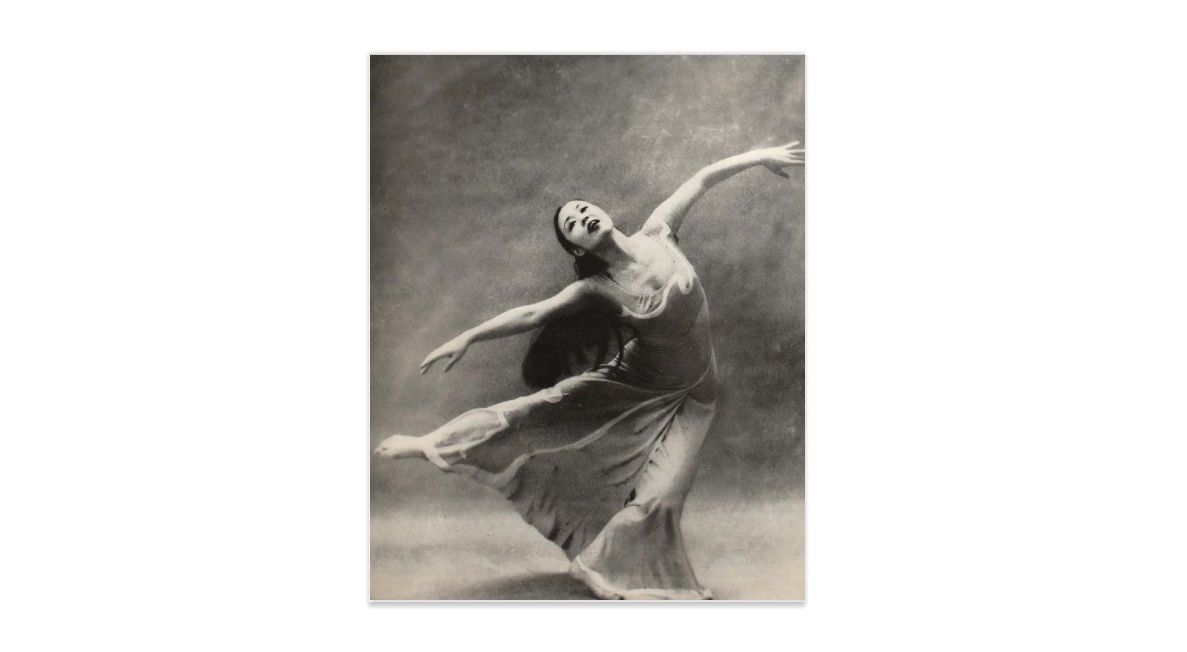

Yuriko Kikuchi, who was a force in the Martha Graham constellation from the 1940s into the current century, passed away on March 8. Known simply as Yuriko, she could project innocence, serenity or a mystical quality onstage. Yuriko also starred on Broadway in The King and I and Flower Drum Song, later staging productions of the former. After choreographing many concerts on her own, she returned to the Graham fold to revive the early works and start a second company. An inspiration to generations of dancers, Yuriko contributed mightily to the Graham legacy.

Born in San Jose, California, in 1920 as Yuriko Amemiya, she was only 3 when her mother, a midwife, sent her back to Japan. The influenza epidemic had claimed the lives of her father and two sisters, and her mother was desperately trying to keep her safe. Yuriko returned to California from age 6 to 9, and then went off again to Tokyo, where she studied with Konami Ishii, a proponent of German Expressionist dance. At age 10, she joined Ishii’s touring group. At 17, she returned to California and studied modern and ballet with Dorothy Lyndall in Los Angeles while also working at a florist shop. Lyndall knew of Yuriko’s bare financial situation and invited her to live in her family’s spare room. Yuriko toured with Lyndall’s junior group and began choreographing with Lyndall’s encouragement.

Her talent attracted attention. She was invited to guest with the UCLA Dance Club, and in the summer of 1941, she played Rima, the bird-woman of William Henry Hudson’s play Green Mansions, with original music by Lou Harrison, with a dance group in San Francisco.

Then, on December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was bombed and everything changed. Yuriko, her mother and stepfather—along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans—were herded into internment camps. Assigned to temporary housing that she described as basically horse stalls, Yuriko taught dance classes that were so popular she was voted the Queen of Tulare Assembly Center. After several months she and her parents were sent to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona. There, too, Yuriko gave dance lessons. The camp administration sanded the floor, installed a piano in Lot 60, and paid her $19 a month, the same amount that a doctor received. Yuriko taught scores of children the dances of The Nutcracker Suite. “I just didn’t want to see the children go nuts. Besides, I didn’t want to go nuts, too.” She later reminisced about how uplifting her lessons were for the children.

In 1943, she was given the option to sign a loyalty oath to the U.S., whereupon she signed, was released and went to New York City. She headed straight to the garment district, where many young women worked. Under Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s decree, however, employers were not hiring any Japanese. But she was such a talented seamstress that an exception was made, and she got a job at a high-end ladies’ shop. Because of her skills, she became the first Japanese to be admitted into the ILGWU union. “I cracked the union,” she said later. In her second job as a seamstress she became floor manager, in charge of 30 or 40 people.

She knocked on the door at the Graham studio, and Martha Graham herself opened it. When Martha asked to see her dance, Yuriko refused because in Japan the tradition was that you need to prepare yourself for a master. So Graham sent her to study with Jane Dudley and Sophie Maslow, who both sang her praises. After that, she was given a scholarship and joined Graham’s class. Graham told her, “I have never said this to anyone, but I’m going to tell you. You are a born dancer.”

In 1944 Japan was still the enemy. So, before Graham cast Yuriko in Primitive Mysteries and American Document, she said to the other dancers: “The war is still on, and I just want to know if anyone objects to my using Yuriko. To me she is the best.” No one objected. Martha asked Yuriko to be her demonstrator for her classes, a position of honor that she held for eight years.

For Yuriko, there was no question that this was the right place for her. The almost religious devotion toward Graham reminded her of “a temple where zazen/seated meditation was practiced” in Japan. “When she did a deep contraction…I said to myself, ‘This is what I want in my body.’ ” In an interview with Francis Mason for Ballet Review, she said, “Working with Martha, you gave all your creativity, all your knowledge—everything to Martha.”

Yuriko left her seamstress position to sew for Graham. All the dancers had to do some sewing, but only Yuriko got paid. Yuriko made many of Graham’s costumes, and in the fitting sessions she got to know the choreographer in a different, more comfortable way than the other dancers. According to Emiko Tokunaga, “Martha was charmed by things Japanese, and the young dancer was the embodiment of this fascination.”

Yuriko created roles in Appalachian Spring (1944), Dark Meadow (1946), Cave of the Heart (1946), Night Journey (1947), Clytemnestra (1958) and Embattled Garden (1958). She regarded Graham’s process as collaborative. Graham would make suggestions, then the dancer would work on her own for a while, and Graham would tweak it. “She would get you to come through clearly in the characters,” Yuriko has said. Working on her role as Eve in Embattled Garden (1958) she felt her own dancing was too smooth. “So I said to Martha, ‘I want to conquer awkwardness.’ And that is how Eve started.”

Not only did Yuriko contribute to the repertoire, but she also made an impact on the Graham technique. She understood the concept of spiraling around the back so well that, according to Tokunaga, Graham credited her with introducing the concept of spiral into class.

In the meantime, Yuriko was also making dances on her own. She gave her first solo concert at the 92nd Street Y in 1946. It was an evening of 10 solos, for which Isamu Noguchi designed some of her costumes. In his book Looking Back in Wonder: Diary of a Dance Critic, Walter Sorell wrote that, “When she went out on her own, something decidedly Eastern could get a hold of her, as in her solo And the Wind, which I thought was ‘a masterpiece in a minor key,’ a work in which she proves her power of expression in three different sets of mood.” The peak years of her choreographic output were between 1964 and ’71, when she brought her company to the Y almost every year.

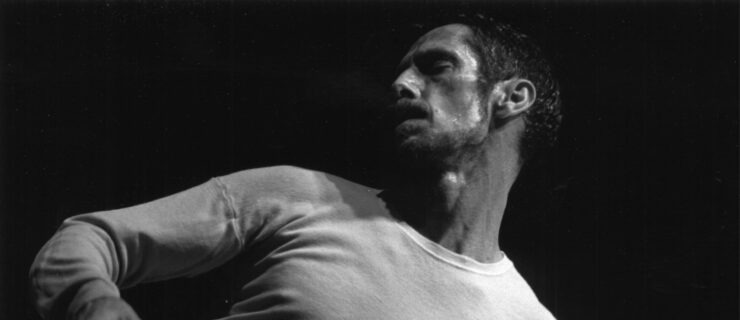

Graham respected Yuriko’s choreographic efforts so much that she included her in a 1948 presentation of works by three of her most promising dancers. The other two were Merce Cunningham and Erick Hawkins.

Yuriko met Charles Kikuchi in 1946 through the post-camp grapevine. They had both been interned at Gila River but had never met—even though he was well aware of her dancing. Their first child, Susan Kikuchi Kivnick, was born in 1948. Because Graham thought of Yuriko as the daughter she never had, she treated Susan like a beloved granddaughter. Susan grew up feeling that the dancers of the Graham company were her second family.

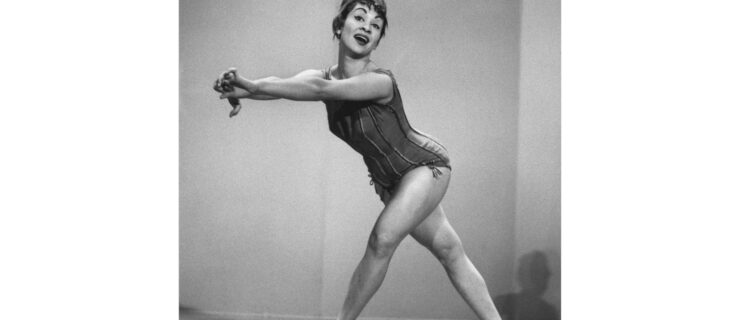

In 1951 Jerome Robbins chose Yuriko for the main dancing role of Eliza in The King and I. She was so vibrant that she became identified with the role, and appeared in the 1956 movie. She brought her daughter to rehearsals of this and other musicals, so it was natural that Susan, starting at age 7, was cast in productions of The King and I, South Pacific and Flower Drum Song. When Yuriko directed the 1977 staging of The King and I starring Yul Brynner, Susan took over the role of Eliza.

At the American Dance Festival in 1964, Primitive Mysteries was revived, with Yuriko in Graham’s role as the Virgin. According to Ernestine Stodelle, in her book Deep Song: The Dance Story of Martha Graham, Yuriko had the “luminous mystical quality” necessary for the role. Critic Eugene Palatsky wrote: “Yuriko, primarily motionless, conveys an inner feeling of such adoration, anguish and awe—merely by raising her head to gaze at the invisible Crucifixion or by extending an arm to bless a suppliant—that a watcher is almost forcibly drawn into her soul to feel the thousand emotions that her mute face expresses.”

At that time, Yuriko was experiencing tensions with Graham. A Guggenheim fellowship in 1967 enabled her to leave the company and concentrate on her own work. But she returned in the late ’70s to restage Dark Meadow.

In 1982, Yuriko taught a three-week course in technique and repertory that became the seed for a second company. The Martha Graham Ensemble, initially led by Yuriko, is now called Graham 2.

After Graham died in 1991, Ron Protas and Linda Hodes, who were co-directors of the main company, named Yuriko an associate artistic director. But she left a few years later because of disagreements with Protas, who was Graham’s problematic (and some say destructive) legal heir.

In 1991 Yuriko won a Bessie Award for reconstructing “Steps in the Street,” a section of Chronicle (1936) that revealed the power of Graham’s all-female choreography.

Reaching a time in her life when she wanted to give back, Yuriko founded the Arigato Project with Yasuko Tokunaga, former director of dance at The Boston Conservatory. (“Arigato” is the Japanese equivalent of “thank you.”) Prompted by an invitation to Susan to stage Appalachian Spring in 2000, the project grew into a series with Yuriko staging Primitive Mysteries, Diversion of Angels and Night Journey, sometimes with Susan. The project extended into setting “Steps in the Street” on students at New York City’s High School of Performing Arts and The New School.

The former Martha Graham dancer Miki Orihara regarded Yuriko not only as a coach and mentor, but also as her “New York mother.” Recalling the way Yuriko demanded the best from each dancer, Orihara said, “She wanted the truth from everybody. She didn’t want anything fake. And she could see it, and she’d say, ‘That’s not it.’ ”

The Martha Hill Dance Fund honored Yuriko with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012, and the following year the Japanese government bestowed upon her the Foreign Minister’s Commendation. While accepting the latter, she said:

“Somehow I often went back to Japan for a creative source. I am 100 percent American, but deep down in my guts, Japan stayed with me. So artistically, I’m also 100 percent Japanese.”

Emiko Tokunaga, Yuriko’s biographer (and sister of Yasuko Tokunaga), commented on Yuriko’s influence on women of Japanese descent, saying, “You have crossed cultural and racial boundaries, which contributed to the mutual understanding and respect for Japan and for America.”

On her 100th birthday, the Martha Graham Dance Company made this video tribute to her.