Introducing Our 2017 “25 to Watch”

Unity Phelan

Corps member, New York City Ballet

Unity Phelan’s long, willowy limbs drip with girlish glamour: She presents her hand to her partner as though she expects a diamond ring to be placed on it. As a matter of fact, she presents her feet the same way. But what makes her so fun to watch is how she infuses her natural elegance with an endearing sense of playfulness. Her articulate lines seem to stretch beyond the confines of her body with a delight that can’t be contained.

Last spring, the 21-year-old New York City Ballet corps member was handpicked by Christopher Wheeldon to perform one of four principal roles in his new American Rhapsody. Partnered by Amar Ramasar, Phelan brought her signature exuberance to the role. That summer, she starred in a premiere by emerging choreographer Claudia Schreier at the Vail International Dance Festival before returning to New York to debut a lead role in NYCB principal Lauren Lovette’s first main-stage choreography. As excited as Phelan might be to take center stage, she’s quickly become a pro at soaking up the spotlight. —Jennifer Stahl

Shimon Ito

Soloist, Miami City Ballet

Shimon Ito grabs attention with his keen physicality—whisking across the stage, whipping out turns, jumping as if onto cushions of air. But then attention becomes admiration as those athletic moments accrue into memorable art. There’s his portrayal of Puck, irrepressibly mischievous, in Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream; his fervor among the sun-kissed companions of Justin Peck’s Heatscape; his superhero-worthy feats in Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room. Even in tricked-up choreography, his dancing runs on a smooth engine, fueled by high-grade classicism. No effect, no matter how forceful, looks superfluous. All this was behind Ito’s recent promotion to soloist at Miami City Ballet. “I try to learn a lot about a ballet,” says Ito, “and translate that to the stage.” —Guillermo Perez

Amanda DeVenuta

Dancer, Kansas City Ballet

In an ethereal pas de deux from Yuri Possokhov’s Diving into the Lilacs last spring, Kansas City Ballet’s Amanda DeVenuta moved with feather-like buoyancy. Her expressive abilities showed not only in her demeanor and gestures, but in every step she took—a hint that this young dancer is just beginning to tap into her wellspring of talent.

In addition to Possokhov’s ballet, the Carmel, New York, native, previously with Minnesota Dance Theatre, has danced a featured role in Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments and made waves with her effervescent performance as the Sugar Plum Fairy in artistic director Devon Carney’s new production of The Nutcracker. Described by Carney as “a rising star” in the company, the 22-year-old is now in her third season with KCB. Says DeVenuta: “Each performance I do I learn more about myself as a person and a dancer.” —Steve Sucato

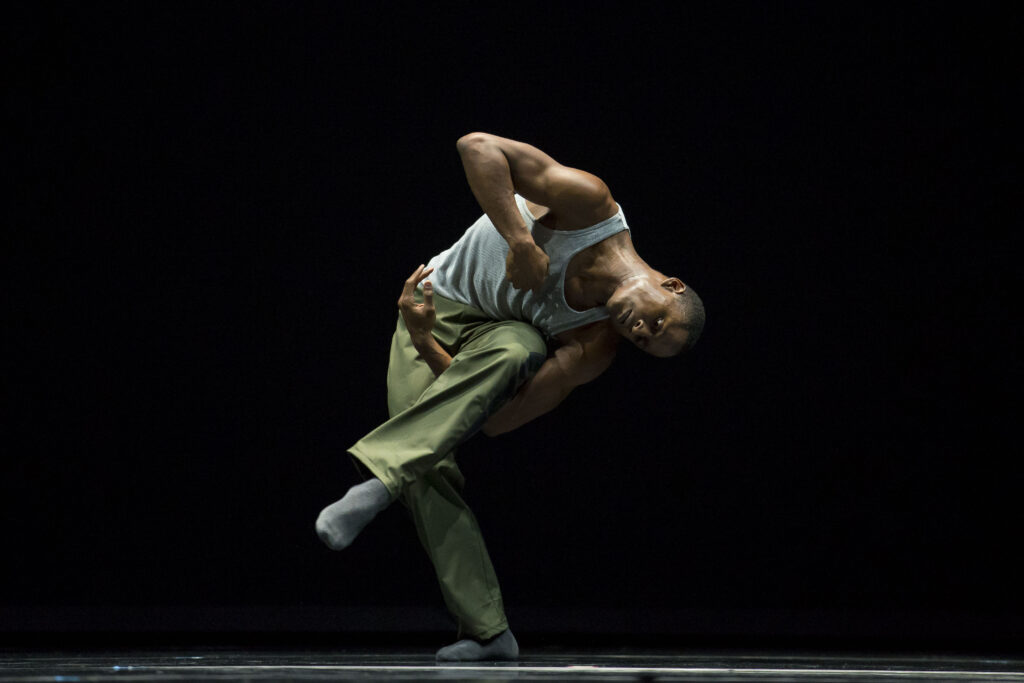

Jeffery Duffy

Dancer, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago

Once a competition kid who danced to Michael Jackson in his grandmother’s basement, Jeffery Duffy, 23, has already forged a fairy-tale career. After training at Dance Theatre of Harlem, the School of American Ballet and The Juilliard School, Duffy’s graduation cap had hardly hit the ground before he signed a contract with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago in 2015. Performing with a level of maturity unusual to new grads, Duffy’s liquid-like flow complemented his veteran co-workers in Alejandro Cerrudo’s Second to Last and Crystal Pite’s Solo Echo last season. Brilliant ensemble dancing and a captivating duet with Kellie Epperheimer in Penny Saunders’ Out of Keeping attracted the notice of the Princess Grace Foundation, earning Duffy a Dance Fellowship in 2016. He has a penchant for repertoire that is less safe, less pretty, less predictable—work that pushes audiences to the edge of discomfort. Performances in a trio of William Forsythe pieces (Quintett, N.N.N.N. and One Flat Thing, reproduced) might best exemplify this, though Duffy will easily excel even further left of center. —Lauren Warnecke

Chun Wai Chan

Soloist, Houston Ballet

Chun Wai Chan oozes confidence—and has the technical chops to warrant it. He joined Houston Ballet’s corps in 2012 already poised for promotion, which he received in 2015. His flash, princely good looks and rock-solid work ethic have made him a go-to dancer for Stanton Welch and visiting choreographers. He was a standout as the Groom in Welch’s new Giselle, dreamy as Waltz man in Balanchine’s Serenade, wild and exacting in Alexander Ekman’s Cacti and mostly airborne for Bluebird in Ben Stevenson’s Sleeping Beauty. His tall, elegant stature, combined with his flawless technique, makes it just a matter of time before he’s Houston Ballet’s next leading man.

Inspired by fellow Chinese-born and former Houston Ballet dancer Li Cunxin, whom he resembles in both height and poise, Chan had Houston on his radar from an early point in his life. “I saw what he did here,” he says, “and I thought: I could do that too.” —Nancy Wozny

Paige Fraser

Dancer, Visceral Dance Chicago

In 2013, Paige Fraser took what she describes as “a giant, scary leap of faith.” After sending a video to Nick Pupillo, who was starting contemporary troupe Visceral Dance Chicago, she was invited to join the inaugural ensemble. Though she barely had the money to fly to Chicago—and knew almost nothing about the city—she said yes.

With her naturally long line, strong technique and dramatic attack, Fraser became a standout in this fast-rising company. Pupillo’s 2016 world premiere Vital showcased her dynamite style with beautifully unforced extensions and gazelle-like leaps. “Paige’s faith and determination completely embody her movement,” Pupillo says. “She has been a driving force in the growth of Visceral.”

Fraser received a 2016 Dance Fellowship from the Princess Grace Foundation and recently made a dance-meets-high-tech commercial for Intel that underscores her ability to blend driving energy and lyricism. As for future dreams, Fraser mentions creating a community center for dance and the arts in the Bronx, her hometown. —Hedy Weiss

Parris Goebel

Commercial choreographer and dancer

Parris Goebel is the feminist force hip hop has been waiting for. The 25-year-old’s work is loud and colorful, and her distinct “polyswagg” style has a mission of empowerment. Her moves display an in-your-face confidence, but they don’t scream to be noticed. She doesn’t strive for popularity or follow trends. She is simply and unapologetically herself, take it or leave it.

But the commercial world is taking it—acclaim follows everything Goebel touches. She’s choreographed for Janet Jackson, Nicki Minaj, Rihanna and Jennifer Lopez; the crews hailing from her New Zealand studio (including the all-female ReQuest) consistently dominate at competitions. Justin Bieber’s 2015 “Sorry” music video that she choreographed, directed and performed in scored her three MTV Video Music Award nominations and nearly 2 billion views on YouTube, placing the viral video among the top four most-watched in site history. And her latest venture into producing her own music, under the name Parri$, proves she’s truly charting her own path, one that’s stamped with plenty of her signature sass. —Courtney Bowers

Elise Cowin

Dancer and choreographer

Elise Cowin’s work is chock-full of contradictions: egalitarian yet meticulous, subtle but transparent, elegant and approachable. Her task-oriented pieces often begin as deep dives of research into arcane topics—the United Kingdom Highway Code or a historical survey of patents for wearable devices designed to allow the body to take flight. Next comes the creation of costumes and props, often of Cowin’s own design. Only then does she begin building her choreography, for dancers of all ages and abilities, to be presented matter-of-factly in galleries, public spaces or on video.

For Up to the Elbows (2016), she manufactured six sandbags, matching the general size, shape and weight of her head, torso, arms and legs. These allowed her to perform a “duet” with a copy of her own body in pieces. Simultaneously formal and fallible, Up to the Elbows extracts the essence from one of Cowin’s inspirations: the novel Don Quixote.

“I’ve gone through phases with the word ‘dance,’ ” Cowin confesses. While earning her MFA in performance from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, “I had faculty tell me, ‘That’s not dance.’ But right now, it sits well with me.” —Zachary Whittenburg

Kayla Collymore

Dancer, METdance

Movement seems elastic under Kayla Collymore’s spell. Nothing appears forced or pushed; she makes dancing look like something that just rolls off the tongue. All lightness and limbs, Collymore apprenticed with the Stephen Petronio Company, danced with Brian Brooks Moving Company and spent a year performing in Beijing before heading to Texas. Now in her second season at Houston’s METdance, the Jersey-girl-turned-Texan is settling into the demands of dancing with a rep company. “I tend to excel in the wet-noodle flow pieces, so I love that at the MET I get to do all kinds of work, including Camille A. Brown’s earthy New Second Line,” says Collymore, who relished the chance to dig into works by Rosie Herrera, Joshua L. Peugh and Katarzyna Skarpetowska this past year. “I’m also ready to take on a leadership role in the company,” she says. “I’ve learned that for a company to be successful we have to network, promote and warmly welcome the numerous renowned choreographers that walk in our doors.” —Nancy Wozny

Elizabeth Wallace

Corps member, Pennsylvania Ballet

It’s hard to miss Elizabeth Wallace. Tall and rangy, the 24-year-old Kentucky native takes special ownership of her roles no matter the size, her lines extending well beyond her 5′ 9″ frame. With silken sophistication and a soaring arabesque, she draws you in with a natural, open presence, her long limbs swallowing space as if air itself were a precious luxury.

Wallace’s Balanchine background is unmistakable in her dancing—she finished her training at the School of American Ballet and danced as an apprentice with New York City Ballet before joining Pennsylvania Ballet in 2012. Artistic director Angel Corella has made significant changes to the roster since his appointment in 2014, but he obviously sees something special in Wallace. She’s danced a steady and wide-ranging stream of leading roles since his arrival, including Christopher Wheeldon’s Liturgy, Wayne McGregor’s Chroma, Choleric in Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments and Queen of the Dryads in Don Quixote. One of a handful of corps dancers still left from the old regime, her future under Corella looks bright. —Amy Brandt

Omari Mizrahi

Dancer, Ephrat Asherie Dance

With flinging arms and powerful spine undulations, Omari Mizrahi is riveting. His knees are so springy that every jump is a pounce. As a member of Ephrat Asherie Dance, he captures the essence of Asherie’samalgam of hip hop, house, funk and Lindy, to which he adds his own blend of West African, house and voguing that he calls AfrikFusion. When he performs it, he can switch on a dime from fiercely masculine to decoratively feminine. Teaching last summer, he said,“West African dance is all about fluid arms that never stop, and in voguing it’s all about striking a pose.”

Born in Senegal, Mizrahi came to the U.S.when he was 6. By 10 he was already dancing in his parents’ troupe. He later earned a name for himself as a voguer in Harlem’s ballroom nightlife, and has since worked with John Legend and Jennifer Hudson. When Asherie or another choreographer shows him a step, he says, “I go back to my memory. The nae nae, a new hip hop dance, reminds me of the way we sway with the West African lamba. The connection speaks to me.” —Wendy Perron

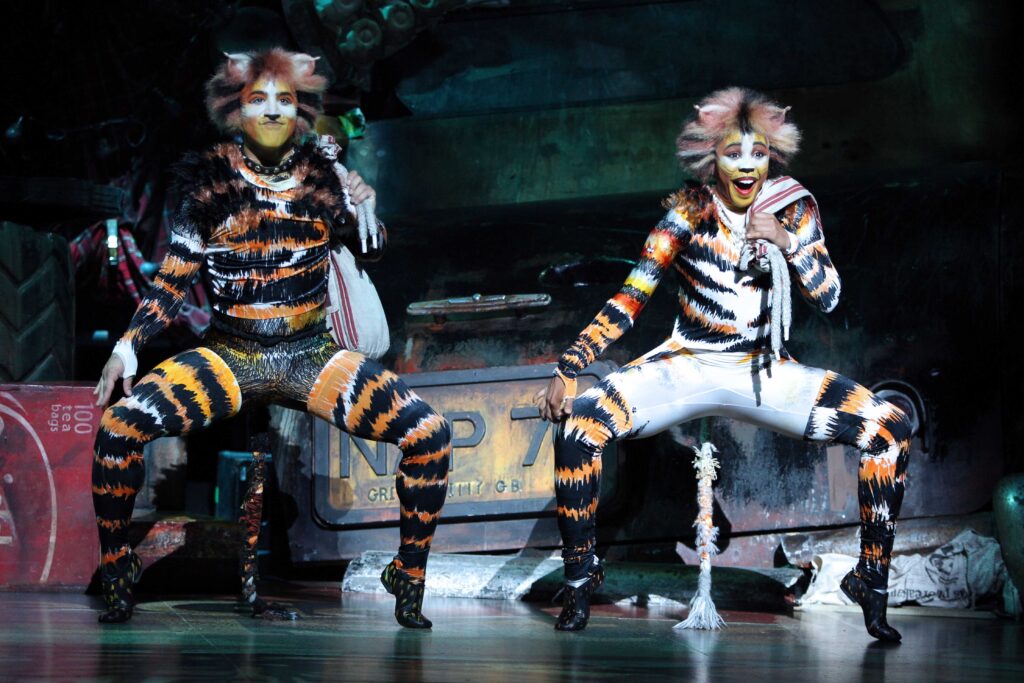

Jess LeProtto

Broadway dancer

When Jess LeProtto is onstage, his enthusiastic charm and sharp comedic instincts win you over immediately. As the mischievous Mungojerrie in Broadway’s current revival of CATS, he makes the choreography’s acrobatic cartwheels and nimble leaps look easy, but can illustrate character—and draw a laugh—just as effectively through a smartly timed facial expression.

A former “So You Think You Can Dance” competitor who’s also performed with American Dance Machine for the 21st Century, LeProtto has the versatility to tackle choreography by everyone from Jerome Robbins to Jack Cole to Andy Blankenbuehler. And at 24, he’s already appeared in several Broadway shows, including the ensembles of Newsies and On the Town. In CATS, he proves that he can shine in a more featured role—and cements his status as a true triple threat. —Suzannah Friscia

Karissa Royster

Broadway tap dancer

When Savion Glover invited her to participate in a creative workshop in 2014, Karissa Royster assumed it would be a short-lived experience. But that project became Shuffle Along, or, The Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed,and Royster made her Broadway debut last spring as both an ensemble performer and dance captain. Her effervescent energy and aplomb as she embodied the production’s period charm and complex history made her a standout amongst a cast of notable hoofers. Playing a Jimtown Flapper and a Jazz Jazmine, one of the musical’s vivacious chorus girls, Royster proved herself a rhythmic chameleon, gliding just as easily through the choreography’s vernacular moves as she did through Glover’s grittier, more hard-hitting combinations.

Royster is currently in rehearsals for new projects with Glover. She plans to continue her voice and acting training in New York City when not teaching or taking tap classes. “Shuffle Along expanded how I view myself as an artist and exposed me to new ways in which I can grow as an entertainer,” she says. With a Broadway show already under her belt, she’ll no doubt be entertaining many audiences to come. —Ryan P. Casey

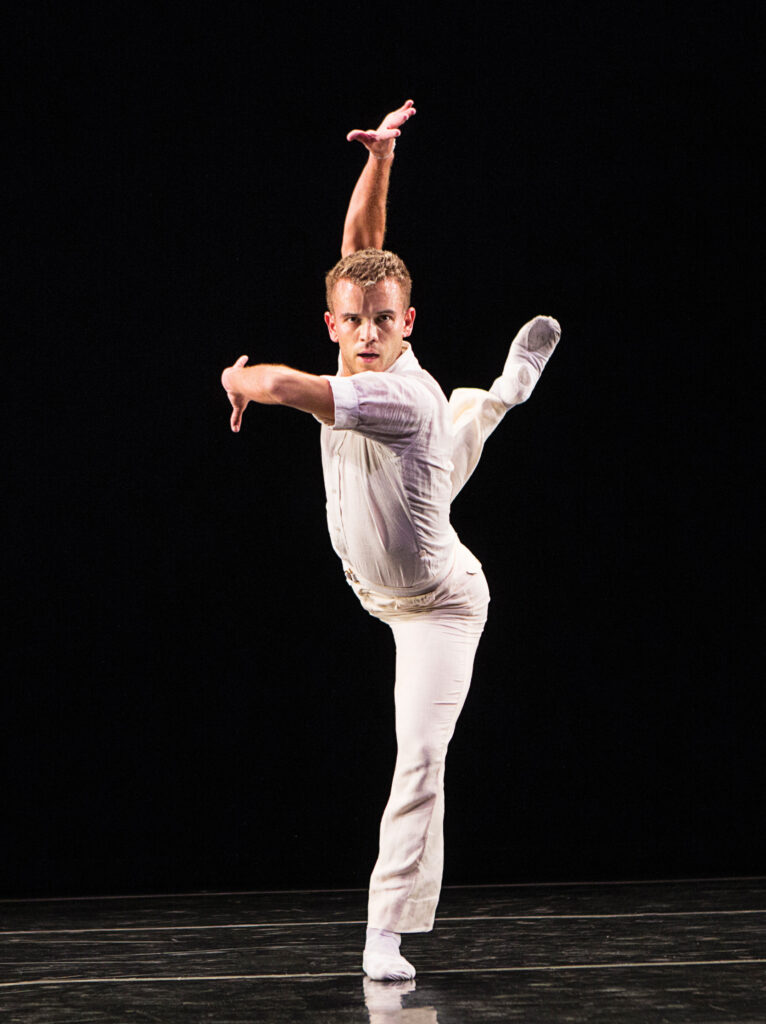

Reed Tankersley

Dancer, Twyla Tharp Dance

When Twyla Tharp was auditioning Reed Tankersley, the two spent a week together in the studio one-on-one. One day Tharp asked why he looked so nervous, and the recent Juilliard graduate responded “…because you’re Twyla Tharp?” She quickly retorted, “We’ll have to get over that.” Get over it he has. Since landing a spot on her 50th-anniversary tour, the dancer has become an essential member of Tharp’s team of veteran performers. In the virtuosic 10-minute-long opening solo of her Brahms Paganini, he balances slippery spontaneity with grounded precision, rendering legible what feels like a choreographic run-on sentence. Endless energy seems to be his mode of operating—when not dancing for Tharp he’s performing with other choreographers like Jonah Bokaer. “I wouldn’t turn down dancing for Ariana Grande,” he says cheekily of his future plans. Who knows? Tankersley has the crisp-yet-malleable technique and youthful openness to do anything. —Lauren Wingenroth

Chitra Vairavan

Dancer and choreographer

With a heart-stopping stare that drags your soul deep into her character’s pain and passion, Chitra Vairavan has been a standout since becoming a founding member of Ananya Dance Theatre. In 2012, with her “Bird” solo in Moreechika: Season of Mirage, this contemporary Indian dancer took flight as she emerged from an undulating heap of bodies with a fluttering poise and winged uplift. Since then, the Tamil (South Indian)-American has spread her wings even further, conveying her progressive brown politics through collaborations and in her own pieces. Schooled in bharatanatyam and muscular, percussive Chhau- and Odissi-based choreography, her fearlessness in revealing the personal as political earned her a 2016 McKnight Fellowship for Dancers. Vairavan’s ardor for igniting change through dance is as innate as it is intentional. Watch her soar. —Camille LeFevre

Mario Bermudez Gil

Dancer and choreographer

Peppered with syncopated rhythms, Mario Bermudez Gil’s Gaga-influenced choreography simmers with flamenco passion. When he takes the stage in one of his works, he captures a striking duality: He is both a simple pedestrian and an uninhibited dancer. What transmits to the viewer is an unabashed love of moving, with wild, high-flying jumps, whirling spins and athletic floorwork seamlessly woven together.

After four transformative years with Batsheva Dance Company—and previously one year each with Gallim Dance and Jennifer Muller/The Works—Bermudez Gil now follows his own choreographic path. This past year he started a company, Marcat Dance, with partner Catherine Coury. Bermudez Gil’s first evening-length piece, Alanda, debuted in Spain last summer. He has already performed his work in Israel, Japan and Korea, winning second place in the Copenhagen International Choreography Competition along the way. Additionally, he was granted a production award to create new work for National Dance Company Wales. The influence of Ohad Naharin inspires many a Batsheva dancer-turned-choreographer, but developing a unique voice can be daunting. Bermudez Gil has a looming legacy to follow but is well on his way to an exciting career of creation. —Jen Peters

Zhiyao Zhang

Corps member, American Ballet Theatre

Zhiyao Zhang may have simultaneously confused and delighted many in the audience for Swan Lake at the Metropolitan Opera House last summer. With a line so aristocratic and a presence of such authority that he could have been mistaken for Prince Siegfried, the American Ballet Theatre corps member excelled as Benno, the prince’s friend. Every airy leap possessed enough thrust to land him yards from where it started, and although he had power to spare, he always displayed a seemingly unforced assurance whether in mime or grands jetés.

His dream roles demonstrate a healthy aversion to typecasting. He says the rogue Birbanto in Le Corsaire intrigues him because the character can be played as a clown, a villain or a villainous clown. Zhang should triumph in each interpretation— possibly in the same performance. —Harris Green

Marc Crousillat

Freelance dancer

At 25, Marc Crousillat has already performed for a who’s who of downtown choreographers, including Netta Yerushalmy and John Jasperse, and the Trisha Brown Dance Company. In Yerushalmy’s dances he oozes character and endearing disjointedness, while in Brown’s he can coolly demonstrate clean geometries or heat up with wild abandon. The 2016 Princess Grace Fellowship recipient credits his appetite for “disrupting” his body’s knowledge and habits to the range in his training at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. He looks at other art forms—cinema, literature—to find more dimensionality in his dancing. Finding time to make his own work’s been hard, but he’ll be going in that direction, too, showing a project at Brooklyn’s Roulette next month. —Lisa Kraus

Martha Nichols

Choreographer and dancer

Martha Nichols is proof that “So You Think You Can Dance” doesn’t have to be the pinnacle of any dancer’s career. After finishing as a top-five-female during the show’s second season, Nichols has since performed in the long-running Cirque du Soleil show Criss Angel Believe in Las Vegas, danced backup for Rihanna’s Diamonds world tour and grooved her way through a Gap commercial. But it’s her more recent foray into choreography that really speaks to her maturity as an artist. Her infectious, funky-fabulous, neon-clad group piece \TILTED\ took home the top prize at last summer’s Capezio A.C.E. Awards. Nichols is hard at work prepping for her own evening-length show this year with her $15,000 production-budget prize money. If it’s anything like \TILTED\, don’t expect your standard dark and funereal contemporary fare: Think fiercely joyful, effortlessly in charge. “Part of me feels like dance is so sad. I’m not that sad,” she says. “I like life. I am a happy person.” —Rachel Rizzuto

Sirui Liu

Senior soloist, Cincinnati Ballet

It takes a particular kind of talent to move audiences with passionate performances, and another to do so while nailing every ballet position with textbook precision. Cincinnati Ballet’s Sirui Liu is one of these rare artists. The newly promoted senior soloist’s spot-on technical ability is something to marvel at, as is her ability to translate those skills into contemporary dance styles with eye-grabbing personality. The 26-year-old showed off her rich abilities this past September in Justin Peck’s playful Capricious Maneuvers, tossing off sparkling pirouettes and jumps as though bubbly with delight. In that same program, she also showed her flexibility, steadiness and ability to access heartfelt emotion in a trio in Ma Cong’s Near Light. Lifted by her shoulders and legs above her two male partners, she was slowly lowered headfirst to clench a rose between her teeth, which she held there throughout the rest of the dreamlike trio. In her sixth season with Cincinnati Ballet, Liu’s career trajectory appears to be on a fast track toward principal. —Steve Sucato

Sarah Lapointe

Dancer, Charlotte Ballet

Charlotte Ballet’s Sarah Lapointe is the prototypical ballerina. She uses her to-die-for extension to send legs skimming past an ear skyward, but the 19-year-old boasts more than just good genes. Lapointe’s performances reveal fluidity in her movement between steps; a sense of grace in every unfolding arm movement leads the eye to delicate and perfectly placed fingers. Possessing technical skills and stage presence beyond her years, Lapointe’s talent is magnetic.

A 2015 National YoungArts Foundation award-winner, Lapointe attended Philadelphia’s The Rock School for Dance Education and has guested with The Washington Ballet. Now in her second season with Charlotte Ballet, she continues to follow a mantra given to her by her artistic director Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux and associate artistic director Patricia McBride: “Don’t be shy, and just go for it.” Charlotte audiences can see her do just that as she brings her formidable extension to a role tailor-made for it: the Lilac Fairy in Bonnefoux’s Sleeping Beauty this March. —Steve Sucato

Meg Foley

Dancer and choreographer

Like an oyster fashioning a pearl, Meg Foley is always chewing on gritty questions. For her 2016 opus Action is Primary, she asked how she could transition years of solo improvisation practice into a collective working experience for multiple dancers. To get there, each of her dancers took on some of Foley’s daily practice, including doing and documenting solo improvisations at 3:15 pm wherever they happened to find themselves. The result was big—three weeks of performances with Foley and her creative collaborators working from their own scores in changing combinations of dancers. They blurred everyday behavior with intentional melodramas and extravagant movement invention. It felt deep, mature and brimming with risk taking.

Foley, 35, is a dancer of extraordinary power. She has been choreographing in Philadelphia since she moved there after college, but her achievement in making Action is Primary promises more work with the potential to shift the ground of dance. Parallel with her own creative work, Foley is building a community hub at The Whole Shebang, a South Philly workspace she co-created in 2015. It’s a place for workshops, special events and, yes, more research into her burning questions. —Lisa Kraus

Ching Ching Wong

Dancer, NW Dance Project

Control and abandon are difficult for any dancer to navigate, but NW Dance Project’s Ching Ching Wong masters both in a single movement. In resident choreographer Ihsan Rustem’s Yidam, half of her body dangles as if free of bones, completely unbound in some precarious, impossible position. Meanwhile her standing leg supports the gorgeous shenanigans going on in the rest of her body, her astonishing ability to have balance while being off balance galvanizing attention at every moment.

There is nothing predictable about the 2015 Princess Grace Award winner’s dancing. “I am working on not being perfect, not apologizing for anything I do onstage, to let my body go through it, and ride it like a wave,” says Wong. “I want to test my body’s physical and emotional capabilities onstage, explode even more, to dive into character. I am looking for more opportunities to be less controlled, to go beyond the boundaries of my 4′ 11 3/4″ body.” —Nancy Wozny

Charlotte Edmonds

Ballet choreographer

Having just turned 20, English choreographer Charlotte Edmonds is remarkably composed and confident. Her choreography has exactly the same qualities. “I’m trying to think of ways you can manipulate classical ballet and change it into something fresher and more modern,” she says of her supple-spined, richly fluid and music-driven movement, which fuses classical and contemporary lines and dynamics. By the age of 16, Edmonds had twice won the Royal Ballet School’s annual choreographic competition and gained her first professional commission. After completing her training at the Rambert School, Royal Ballet director Kevin O’Hare created a brand-new role for her in 2015: Royal Ballet Young Choreographer, where she is mentored by Wayne McGregor.

Edmonds is a fan of Crystal Pite, Mats Ek and William Forsythe, and she’s particularly interested in contemporary narratives—she recently worked on an adaptation of a Zadie Smith story for Northern Ballet. Yet more than anything, she has a desire to connect with deep emotions and move her audience. A timeless aim from a very of-the-moment young talent. —Lyndsey Winship

Margarita Shrainer

Corps member, Bolshoi Ballet

When an unknown name appeared on the Bolshoi’s principal casting in London last summer, ballet-goers took notice. At 22, despite being ill, the Bolshoi Ballet’s Margarita Shrainer made her debut as Kitri during the tour, the only corps dancer cast in a leading role. “It was a pleasantly shocking experience, completely unexpected,” she says.

With her combination of long lines, speed and buoyancy, Shrainer is a pure product of the Moscow school. She was billed as a potential star when she graduated from the Bolshoi Ballet Academy in 2011, yet only minor roles came her way in her first seasons. When new Bolshoi director Makhar Vaziev arrived last March, however, he immediately spotted Shrainer. A dizzying string of debuts followed, with The Flames of Paris, La Sylphide, “Rubies” and Don Quixote in just three months.

A self-described workaholic, Shrainer rose to the challenge under the guidance of her coach Nadezhda Pavlova. Her joyful, expressive presence onstage bodes well for the future, and she is determined to seize the moment: “If I continue working like I do, if I listen, all my dreams can come true. Everything is in my hands—with Makhar Vaziev’s help!” —Laura Cappelle