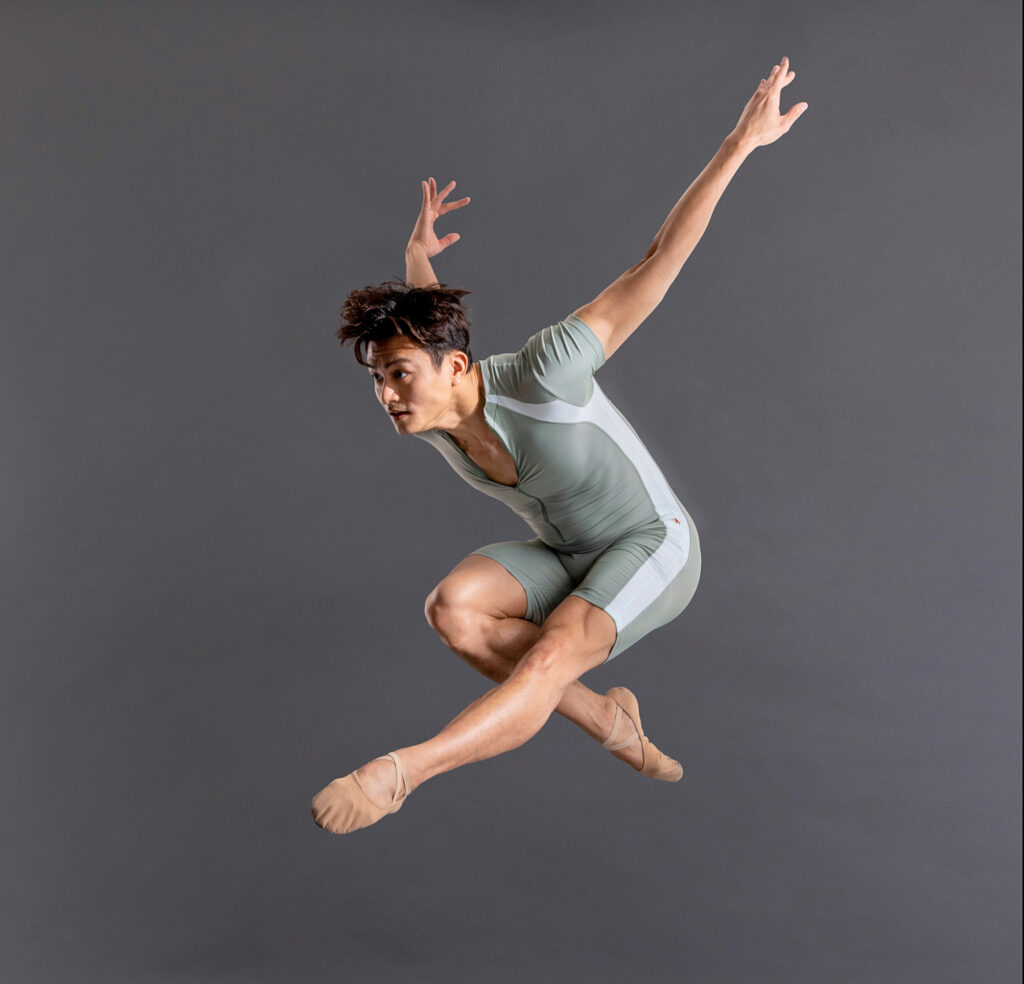

Chun Wai Chan, New York City Ballet’s First Chinese Principal, Brings Hunger and Humility to His Multinational Career

Some dancers reveal their truest selves in performance, heightening and deepening the qualities that make them who they are. Onstage, Chun Wai Chan is forthright and generous, regal but not aloof, with an open countenance that complements an uncluttered technique. Those impressions hold true offstage, where the New York City Ballet principal is candid, sincere and warm—hospitable, even, as if hosting a dinner party rather than sitting for a magazine interview. (He is as eager to ask questions as to answer them.)

Both settings evince Chan’s abundant curiosity: The 30-year-old dancer is perpetually searching for new ways to express himself fully and authentically. Though he makes a natural prince, he has also sought out contemporary perspectives on classical ballet, a pursuit that has led him across oceans and countries. He has learned an array of languages—spoken and danced, onstage and online—with astonishing speed. As the first principal dancer from China at NYCB, he has embraced his role model status, hoping to help reimagine a Eurocentric art form for an international age.

“Chun Wai is the ultimate sponge,” says Houston Ballet first soloist Harper Watters, Chan’s friend and former colleague. “He’s always on the hunt, always hungry, always looking for new information.”

Born in Huizhou, in China’s Guangdong Province, Chan followed one of his three older sisters into dance class at age 6. His parents, busy running their sweater importing and exporting business, and envisioning a future for Chan as a doctor or lawyer, saw the studio as mostly “a great daycare,” Chan says. But in dance he found freedom from the pressures of his academic classes, which were huge (“imagine 70 of us, all sitting right next to each other,” he says) and intensely competitive.

The stakes changed considerably when Chan earned acceptance to Guangzhou Art School’s selective ballet program at age 11. His tight-knit family held a vote on whether or not the young dancer should be allowed to attend. The nos from his parents and grandparents outweighed his sisters’ yeses.

Chan recognized that this was an inflection point. “In China, once you decide not to pursue the art form this way, you have to focus on academic school,” he explains. He wrote his father a letter pleading his case. “I just knew that if I didn’t dance, I wouldn’t be me anymore,” he says.

His parents agreed to let him go. Determined to make the most of the opportunity, Chan worked hard at the Vaganova-based Guangzhou school. But he kept his eyes open, too. At 16, he began attending ballet competitions abroad, which gave him a taste of the international ballet scene, a world he’d glimpsed through the 2009 film Mao’s Last Dancer.

At the 2010 Prix de Lausanne, Chan received nine offers from ballet companies and schools. He chose Houston Ballet II, partly because he’d been impressed by the Houston dancers who had performed at the Prix—“their energy, it was shining,” he says—and partly because Houston Ballet was where Li Cunxin, the Chinese ballet star at the center of Mao’s Last Dancer, had spent much of his career.

Chan arrived in Texas knowing little English, and found himself overwhelmed by Houston Ballet II’s heavy touring schedule. After earning a spot in Houston Ballet’s corps in 2012, he hurt first his thumb and then his ankle, forcing him to take breaks from performing. Feeling unmoored, Chan considered leaving the company to attend the University of Arizona, where he’d received a full scholarship.

Then artistic director Stanton Welch cast him as Romeo—fifth string—in Romeo and Juliet. “The happiness of covering Romeo in the fifth cast, for me, was more than the scholarship to the university,” Chan says. “And so I realized, I think I belong to the dance world.”

Over time, Chan made a home for himself in Houston, where he danced featured roles in a range of classical and contemporary repertory, particularly works by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. He and Watters bonded during backstage tapings of Watters’ playful YouTube series “The Pre Show,” which introduced the internet to Chan’s goofball side.

“Chun Wai picks up on so many things, not just when it comes to the dance elements, but also in terms of social interaction,” Watters says of their rapport on “The Pre Show.” “He immediately found a way to bounce off my sense of humor. I can be pretty fast, I can push people that way, but he always kept up.”

Watters encouraged Chan to develop his own online presence, pointing out that the hours Chan spent playing Candy Crush Saga—he’d become fixated on the game—could be put to better use. Chan says, “I started thinking, What if I play Instagram, play social media, as the game instead?” After his brother-in-law, a policeman in China, asked for some stretching tips, Chan began posting fitness and technique tutorials to YouTube. Simple, useful and endearingly unstuffy, they earned his Chunner Studio channel a large following.

In 2017, Chan became a principal at Houston Ballet. Soon after, he and Welch worked out a special arrangement: Chan would sign half-year contracts with Houston Ballet, allowing him to spend a good chunk of each season guesting with Hong Kong Ballet—much closer to his much-missed family. The pieces of Chan’s professional life seemed to be clicking into place.

But when NYCB resident choreographer and artistic advisor Justin Peck cast Chan in Reflections, a new work he was creating for Houston Ballet in 2019, Chan unlocked something new. “There was a sense of freedom in Justin’s movement that made me think, Oh, I’m craving more of this!” he says. Peck kept expanding Chan’s role in the ballet: Initially part of a trio, he gained a pas de deux and then a solo of his own. “He’s really the ideal collaborator,” Peck says. “He’s incredibly present, and he brings his full self.”

Ahead of the premiere, Chan—being “an excellent Houston host,” as Peck says—took Peck and lighting designer Brandon Stirling Baker out for Peking duck. The dinner conversation turned to New York City, and NYCB. “Chun Wai was very curious about New York as a broader place,” Peck says, “but also as this kind of mecca for dance.” If Chan was interested in NYCB, Peck said, he was the guy to talk to.

Chan was interested. But he was also conflicted. He felt attached to his community in Houston, and appreciative of Welch’s support and flexibility. In a full-circle moment, Chan’s family once again helped him make a crucial career call—this time, from a very different perspective. “They said go!” he says. “Go to another company, another city, to fight for what you dream for. No matter what position they offer you, go.”

In early 2020, Chan traveled to New York City to take class with NYCB. Though the company almost never hires dancers who haven’t trained at its own School of American Ballet, Chan was offered a soloist contract for that fall.

The pandemic paused that plan. During COVID-19 shutdowns, Chan returned home to China. While there, he appeared on the second season of “Dance Smash,” a popular Chinese reality-television show, where he performed a range of styles—ballet, contemporary, Chinese folk dance. He made it to the competition’s final four, gaining thousands of new fans along the way, and enjoyed learning how to perform for the camera. Chan signed with an agency in China that urged him to capitalize on his “Dance Smash” success by pursuing more television, film and commercial work. But he was itching to get back to professional ballet, and to New York.

Chan arrived at NYCB in August 2021. His first few months at the company were a full-immersion course in the Balanchine style, to which he’d had relatively little exposure. That might have been overwhelming to a different initiate, but Chan says he appreciated the big dunk. “It’s like learning a different language,” he says. “Once you’re working in this environment where it’s all around you, it’s much easier.”

Now Chan is using everything in his varied technical arsenal to attack a swath of NYCB’s repertory. He has become a particular muse to Peck, who created a leading role for Chan in his recent premiere, Copland Dance Episodes. The ballet’s abstract, contemporary storytelling allowed Chan to dance as his 21st-century self, rather than inhabit an old-world ideal. “He realized that he didn’t have to kind of put that crown on,” Peck says.

Chan was first surprised, and then touched, when young dancers of color began saying that his career gave them hope for their own. A flurry of press attention accompanied his promotion to principal last May—at the time he was the first Chinese dancer and only the fourth Asian dancer to reach that rank at NYCB (Mira Nadon’s promotion in February means there have now been five Asian principals at the company). He says he tries to bring aspects of his heritage into his art. “Growing up in China, I learned a lot about Confucius’ ideal, the Chinese culture of being humble and polite,” he says. “And that’s how I want to work and interact with people.”

Chan is modest about the scope of his influence. But Georgina Pazcoguin, NYCB soloist and co-founder of the advocacy organization Final Bow for Yellowface, which aims to improve Asian representation in ballet, says Chan embodies change every time he steps onstage. “It’s really exciting to see someone like Chun Wai as the Cavalier, as Prince Désiré,” she says. “And now he’s being given chances to not play the prince, too. He’s showing that he can be all of these things.”

What else might Chan be someday? Maybe an artistic director. He has been taking classes in organizational leadership at Fordham University. “Who knows if I’ll get director offers—maybe in 10 years!” He chuckles. “But I want to be prepared.” He has also been studying acting in case Broadway or Hollywood come calling, which “would be a fun adventure,” he says.

Chan piles those courses atop a furious performance schedule, often dancing five shows a week when NYCB is in season. In March, he also returned to Houston Ballet for his COVID-delayed farewell shows, playing Romeo (first cast, this time) in Welch’s Romeo and Juliet. But he still makes time for decompression sessions with Jovani Furlan and Gilbert Bolden III, two of his closest friends at NYCB; for karaoke outings, where he favors songs by Sam Smith and Justin Timberlake; and for exploring New York City. “He’s not a tunnel-vision ballet person—he’s taken to New York with such enthusiasm,” Peck says. “He goes out, he sees shows, he goes to restaurants. He’s expanding his community here.”

However expansive his horizons, Chan thinks he has plenty more to learn inside ballet. “One of the reasons ballet is so fun to me is because there’s always something to fix next time, always something to work on, always new challenges, if you’re looking for them,” he says. “You’re always growing and growing and growing.”