Why Commercial Star Emma Portner Is Exploding Into the Concert Dance World Right Now

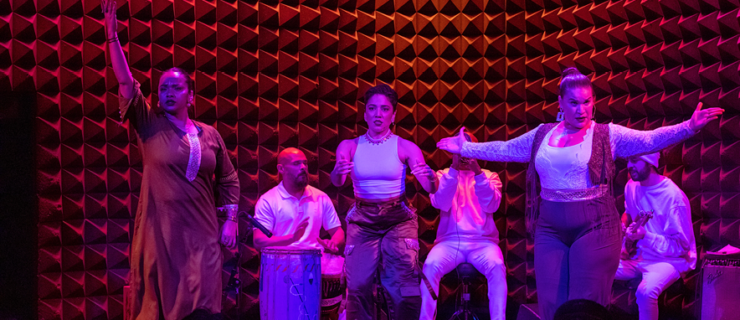

Clad in her signature loose black T-shirt and baggy gym shorts, Emma Portner is standing in a cavernous industrial space in downtown Los Angeles. A glass box—big enough to fit five dancers with only a little room to maneuver inside—sits in the middle. The five performers, Portner included, are standing inside it, side by side, palms on the glass.

“Question,” Portner asks. “Are we looking at our hands?”

She steps out to watch the others try the phrase, and adds a few more steps. Quick, staccato movement, legs kicking out, torsos swiveling around, fists hitting glass. “This is a puzzle,” she says, almost to herself. “I’m not sure I’ll like it.” The statement, like so many, is punctured with a sweet, nervous laugh.

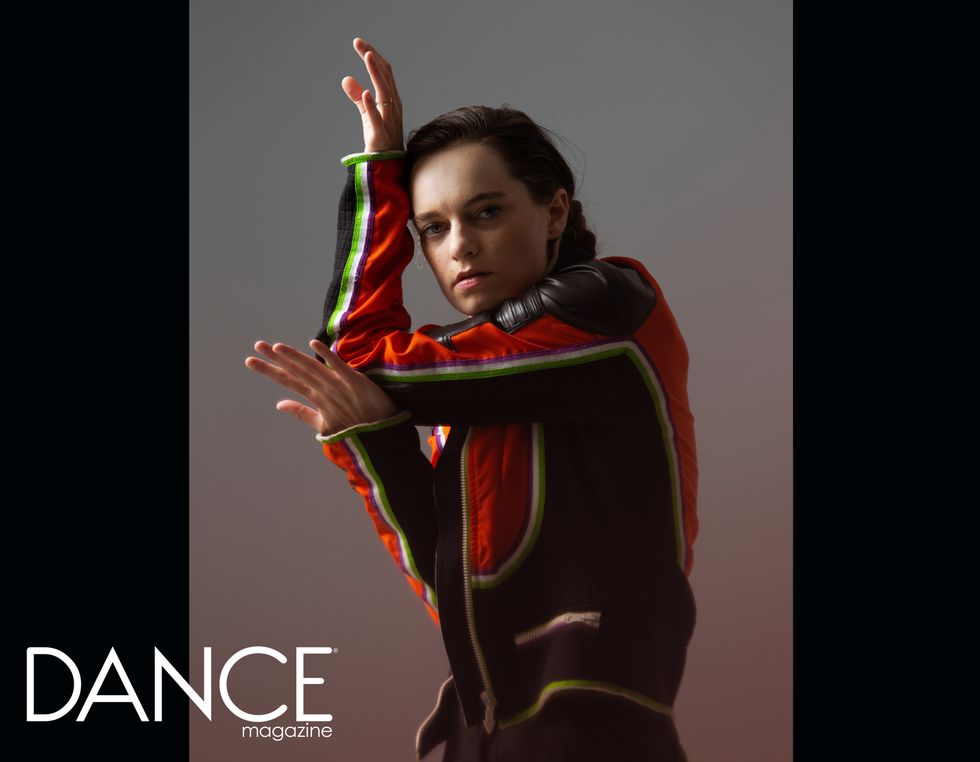

Portner, 23, may be soft-spoken, but she’s a powerhouse mover. Anyone who has seen her Instagram videos can recognize the ferocity with which she throws her body—and seemingly her soul—into each moment.

That said, the energy in the rehearsal space is anything but frenetic. A calm, collaborative feel permeates. “What do we need to do next?” she asks the dancers. “Is everyone okay?”

How Fame Has Changed Her

Portner’s meteoric rise is almost unheard of in the dance world. In addition to her recent commercial work, which includes choreographing for a new Netflix show and music artist Maggie Rogers’ most recent video, in September Portner premieres a piece with Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. In January, she’ll choreograph a new work for New York City Ballet—a major coup in the ballet world, and a whole new forum for Portner.

“Not a lot of young queer women are asked to do these things, especially in the ballet world,” she says. “I’m proud to be part of the revolution. It makes me feel a certain type of value you don’t often find.”

Hubbard Street artistic director Glenn Edgerton says he was intrigued to commission one of Portner’s first big concert dance projects because of the inventiveness and quirkiness of her choreography. “She has a sense of deep imagination,” he says. “It feels like she’s on the brink of exploding.”

Portner has been choreographing since about age 14, but the spotlight on her intensified in 2015, when she choreographed and starred in Justin Bieber’s “Life Is Worth Living.” The video went viral, garnering more than 50 million views.

Although she already had a big Instagram following, she was still self-producing poorly attended shows in New York City, and sweeping the floor at Battery Dance to get reduced-rate studio space. Suddenly she was being approached for all kinds of work—choreographing for music videos and TV shows, dancing briefly with Michelle Dorrance, and choreographing Bat Out of Hell, a West End musical (as the youngest woman to ever do so).

The attention became even more relentless when news broke in January 2018 of her marriage to the actress Ellen Page, and she started posting videos of the two dancing together in rough and sensual, intense and physically demanding duets.

For an artist whose work is about exploring her own self-declared “brokenness,” this newfound attention is complicated. It is a lucky, privileged challenge, she is quick to add, but one nonetheless. “What’s most challenging is remaining open and courageous enough in such a public platform,” she says. “Pain in artistic work can be magnetic to some people. The more successful you are, the more you’re a target.”

Unexpected fame has meant that her work and private life are now public claim, and she needs to move through the world with more caution. There’s a “before and after,” she says, that no one can prepare you for.

Why She’s Grateful For Loneliness and Rejection

The one thing that hasn’t changed? Dance is still what she wants to share with the world, which is all she’s wanted to do since her days as a lonely, quiet child. “I was extremely grateful for dance because it was my lifeline, my safe zone, my fuel, my refuge,” she says.

Trained in competition dance from age 3 in her native Ottawa, Canada, Portner went on to study at Canada’s National Ballet School, but didn’t pursue ballet actively. “I wanted to express myself in so many ways,” she says, “and I didn’t think ballet could hold it all.”

Although she auditioned for Juilliard, she was immediately cut. “I’m grateful for my broken Juilliard dream,” she says. “I would have just been starting my career now!”

Instead, she studied at The Ailey School, and at age 17 took a career-changing summer intensive with RUBBERBANDance. Each day there would end with a cipher—a long, circle-based improv session—but Portner was too intimidated to participate.

One day, Anne Plamondon, the company’s associate artist, gave her a talking-to. “She told me, ‘You’re being absolutely selfish with your talent,’ ” Portner says. “I realized that by not contributing, by staying quiet and not giving of yourself, you’ll never know the impact you can have.”

Portner finally went into the cipher and danced with total abandon. Everyone looked at each other, shocked. And then the cipher ended. “I thought I’d done something wrong!” she says. “I still get emails from people: ‘Remember when you shut the cipher down?’ It was such a pivotal moment in my training.”

Making Work As a Young Queer Female

One of the most remarkable things about Portner’s work—as well as her own dancing—is that while the movement itself defies categorization (is it modern, contemporary, hip hop?), there is an intuitive, organic and vibrant feel to it. As an audience member, you know where you are, but you have no idea where you’re going. And yet you trust Portner to take you there because the surprises along the way are a total delight, jolting shocks to the system. There is something magnetic and destabilizing about it.

“There’s always a lot of gravity to her choreography,” says Keanu Uchida, who has danced with Portner since they were kids. “As a queer artist, Emma finds it important to have that be part of the work, even if it’s not at the forefront of what a particular project is about, it’s still there, part of us in some way.”

This was true of the piece with the glass box that I watched Portner and Uchida rehearse in L.A. It was for a short film commissioned by the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland, inspired by Francis Bacon’s paintings and sculptures by Alberto Giacometti. Portner took a starkly political bent on these artists’ work: A black woman is trapped inside the glass box (reminiscent of Bacon’s glass boxes), “which is a comment on many years of black history,” Portner says. The white male dancer is the only one who moves freely in and out of the glass box, but in the end, this woman of color—standing on a chair—grows taller than anyone else in the piece.

“I’m a young queer female,” Portner says, “so I have to talk about how a young queer female is responding to pieces of art by old white men, during a time when women didn’t have the same access to making work.”

Despite her exposure to myriad genres, Portner seems to have become an artist from her explorations alone in the studio, most of which she records and studies. “The amount of time I’ve spent alone in a studio training myself versus with other people is about 50/50,” she says. “I can zone in on my own heart. Then when I enter a process, I take the horse blinders off.”

Unsurprisingly, Her Schedule Is Booked Until 2020

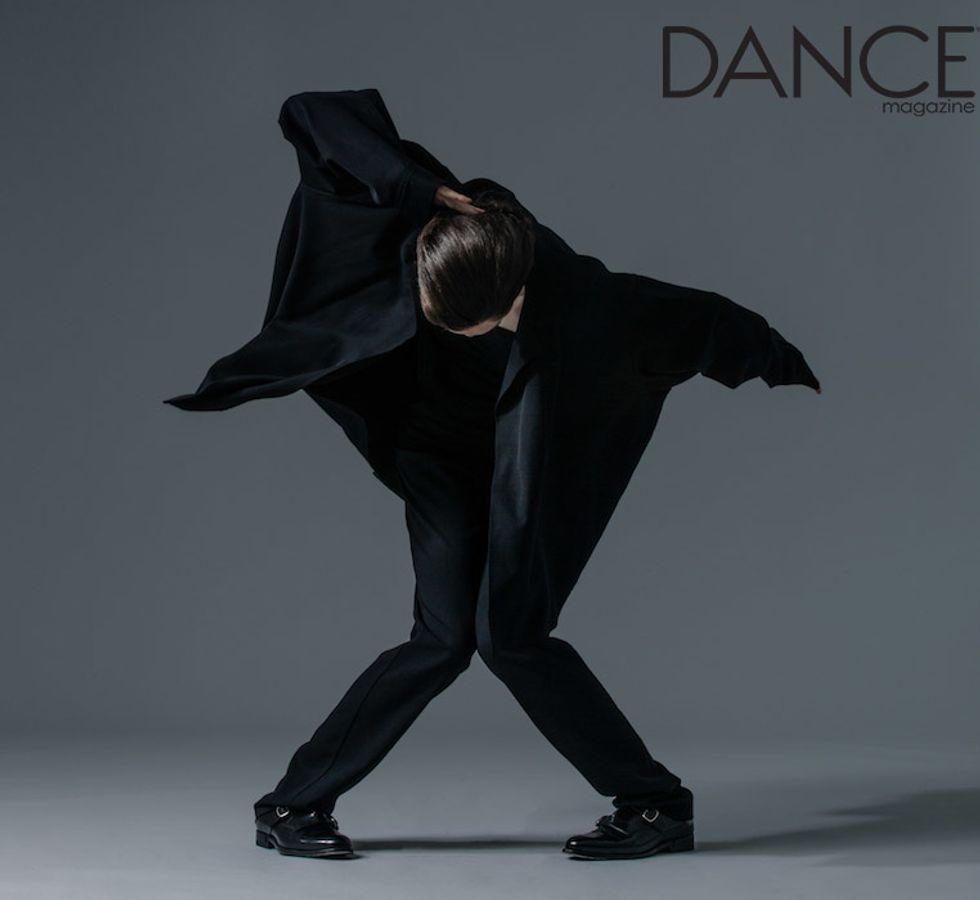

Portner dreams of Broadway, starting a residency, and her own company. Photo by Quinn Wharton.

Portner dreams of Broadway, starting a residency, and her own company. Photo by Quinn Wharton.

The next few years are so busy Portner wistfully talks about taking a break some time in 2020. She hopes to start a small company (à la Crystal Pite); to try out acting, directing, and editing and coloring film; to dance on Broadway; to open a dance residency in Halifax, Nova Scotia; and to spend more time with Page, whom she rarely gets to see.

“In 2016, I reached a point where I felt like I’d achieved all I could possibly achieve—and then this year happened,” she says.

In spite of the incredible demands of the last few years, dance is still where Portner finds solace. “It’s where I feel safest, heard, loved. It’s where I feel hated sometimes, and that’s okay too,” she says. “No matter what, I always hope to be dancing.”