New Insights into Martha Graham

Martha Graham was—and is—fascinating. But rarely has a biographer stretched our knowledge of her life and times as much as Neil Baldwin in his new book, Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern. In a recent series of three presentations (two in the Graham Studio Series and one at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts), he talked about his research, and the Martha Graham Dance Company showed archival footage of Primitive Mysteries (1931) as well as live performances of two iconic solos: Ekstasis (1933) and Medea’s sorceress solo from Cave of the Heart (1946).

Interviewed by Janet Eilber, artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company, Baldwin spoke of his epiphany while watching senior artistic associate Denise Vale lead a rehearsal of “Steps in the Street,” from Chronicle (1936), at Montclair State University. As a writer whose area is American modernism, he realized that Graham was the “connective tissue” in his study of modernism, that her work was crucial to an understanding of this period in American history. But it took him four years to screw up the courage to contact the Graham company. Having written biographies on Thomas Edison, artist Man Ray, and poet William Carlos Williams, he said: “I spent my life up here [pointing to his head] and now I feel it here [pointing to his gut].”

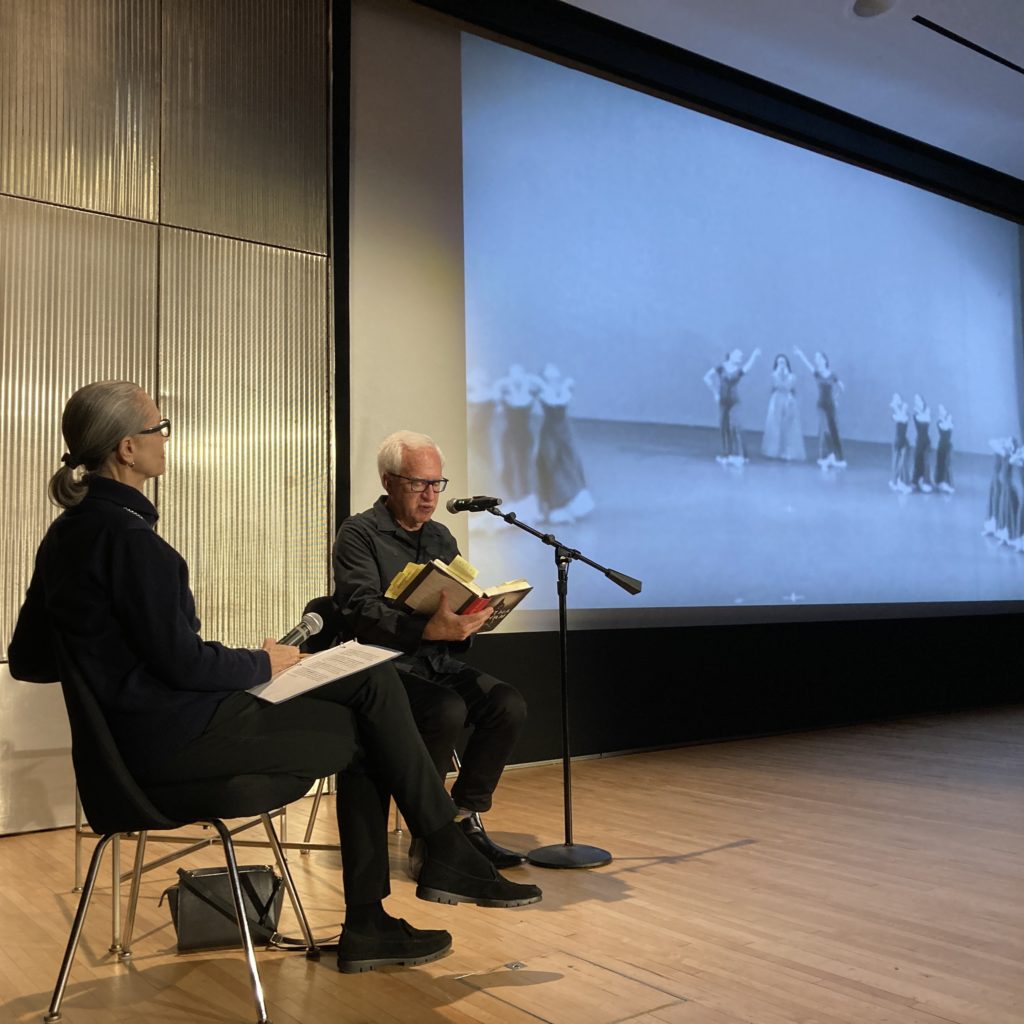

Eilber and Baldwin decided to experiment with reading and dancing. He read his description of Graham’s masterwork Primitive Mysteries while a grainy 1964 film showed a group section with Yuriko as the Virgin. The timing of his words allowed us to see some images (for example, reaching toward a distant cross) that we might have missed, and to appreciate how starkly simple and well-crafted this ritual is.

It was exciting to see the Graham solos performed by superb dancers in intimate spaces. In the sensual Ekstasis, reimagined by Virginie Mécène, Natasha M. Diamond-Walker performed at the Graham studio, moving as though molding the clay of her body. At the New York Public Library’ of the Performing Art’s Bruno Walter Auditorium, Anne Souder took a slightly more percussive approach. In both cases, the restrained sexuality gave a sense of heightened drama to the angular designs of the body. On the other hand, Medea’s post-murderous dance is so psychologically creepy that Eilber joked that she and Baldwin had to leave the space because she knew that this solo scares him. Leslie Andrea Williams, in the Graham studio, and Xin Ying, at the library, gave different shadings to the full-body shudderings of this crazed, obsessive dance.

Although the book is more than 500 pages, it covers only the first half of Graham’s long life, when she was actively creating modernist dance for the concert stage. While Baldwin cannot offer the firsthand knowledge of Stuart Hodes’ Onstage with Martha Graham, he provides a fascinating intellectual context for her work. Baldwin’s book is about “how the ecosystem of her era fed her genius,” explained Eilber. Sure, there’s plenty in the book about her relationships with Louis Horst and Erick Hawkins, but you will also learn how reading Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung affected the young dance artist.

As a poet, Baldwin found his own common ground with Graham. “Poetry is making,” he said. “Poetry helped me to come to terms with dance.” He waxed particularly gleeful when talking about his discovery of Graham’s writings in high school. He called the teenager’s short stories “brilliant.” She also led her girls’ basketball team! So, the intellectual and the physical sides of her were already active. Years later, those two sides interacted with a dynamism that erupted into dance modernism. These three events were part of Eilber’s ongoing efforts to give a range of entry points into Graham’s monumental work. (The 100th anniversary of the company is only four years away!) For anyone hungry to read about Graham and her world—or “ecosystem,” as Eilber put it—this book will be challenging and satisfying.