The 12 Most Groundbreaking Musicals of the Last Six Decades

Broadway musicals have been on my mind for more than half a century. I discovered them in grade school, not in a theater but electronically. On the radio, every weeknight an otherwise boring local station would play a cast album in its entirety; on television, periodically Ed Sullivan’s Sunday night variety show would feature an excerpt from the latest hit—numbers from Bye Bye Birdie, West Side Story, Camelot, Flower Drum Song.

But theater lives in the here and now, and I was in middle school when I attended my first Broadway musical, Gypsy—based, of all things, on the early life of the famed burlesque queen Gypsy Rose Lee. I didn’t know who Jerome Robbins was, but I recognized genius when I saw it—kids morphing into adults as a dance number progresses, hilarious stripping routines, a pas de deux giving concrete shape to the romantic yearnings of an ugly duckling. It proved the birth of a lifelong habit, indulged for the last 18 years in the pages of this magazine. But all long runs eventually end, and it’s time to say good-bye to the “On Broadway” column. It’s not the last of our Broadway coverage—there’s too much great work being created and performed, and you can count on hearing from me in print and online.

Still, it seems an appropriate time to sort through 50-plus years of musicals to pick out the ones that meant the most, that opened my eyes to the possibilities of this ever-evolving, ever-fascinating form. Call it the Sylvi Awards—not for the best, or for my favorites, or for any other ranking you can dream up. I do love them, but they’re here because these are the musicals that showed me something I’d never seen before.

1959: Gypsy

Possibly the high-water mark for the mature American musical, which came into being in the 1940s, featuring adult love stories, songs headed for the charts, and dance inextricably tied to storytelling. The current revivals of My Fair Lady and Carousel prove that this kind of show, done well, is, and always will be, ravishing.

1968: Hair

I was in college, the Vietnam War was raging, hippies were taking over the East Village, and suddenly it was all happening on Broadway, in a show that tapped into a generation—something that didn’t really happen again until 1996, when Rent arrived. Hair‘s anarchic spirit went on to infuse and inspire other break-the-mold musicals, like the The Me Nobody Knows, Spring Awakening and American Idiot. And its feral physical style, devised by director Tom O’Horgan and dance director Julie Arenal, introduced a new freedom to Broadway movement.

1972: Pippin

My first Bob Fosse musical thrilled me from its opening moments—a black stage pierced only by brightly lit, slowly moving jazz hands. Gradually spreading light revealed the incomparable Ben Vereen and a superlative dance ensemble (that included Ann Reinking) in “Magic to Do.” But beyond the wonderful score and the indelible Fosse choreography, Pippin stands out for its meta-musical framing—a show that acknowledges that it’s a show, paving the way for later delights like The Drowsy Chaperone and Passing Strange.

1976: Pacific Overtures

It opened in a season dominated by two dance-driven masterpieces, A Chorus Line and Chicago. But this one, with its kabuki-influenced choreography by Patricia Birch and its deeply serious exploration of the relationship between Japan and the United States, revealed that musical theater could tackle complex historical material in fresh and entertaining ways, and with unlikely dance styles. Hello, Hamilton.

1978: Ain’t Misbehavin’

Arguably the first true jukebox musical, this compilation of Fats Waller numbers was given a unique, elegant look by Arthur Faria. He borrowed vocabulary from the stylized arms of Thai dance, setting a high choreographic standard for songbook shows to come, like All Shook Up and Jersey Boys.

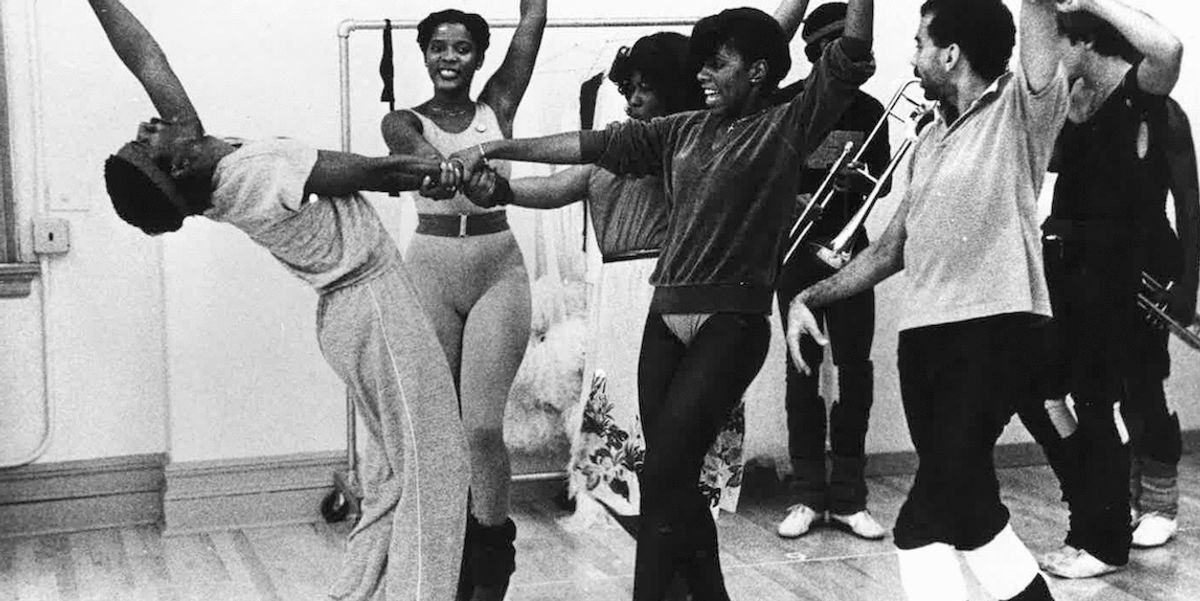

1981: Dreamgirls

Michael Bennett is best remembered as the creator of A Chorus Line, but in this, he choreographed not just the dances but the set’s gliding black towers, lending its showbiz story a strikingly new cinematic flow. Set elements that move along with the action are now commonplace in the theater, but Dreamgirls brought more than a fresh look to Broadway. It accurately captured the way black music and dance styles swept out of Detroit and into white America in the ’60s, opening a path for wondrous shows like Sarafina! and Memphis.

1984: Sunday in the Park with George

This brilliant Sondheim musical centering on an iconic painting by Georges Seurat had no dance numbers per se, but it was about art, thrusting musicals into new aesthetic territory. With its moving depiction of the obsessive struggles and hard-won rewards of creation, the show says something essential about all artists. And when George sings about finishing the hat in his painting, he could also be a dancer or choreographer: “Look, I made a dance where there never was a dance.”

1997: The Lion King

The sheer volume and variety of its theatrical artistry—blame Julie Taymor and Garth Fagan—created the Disney juggernaut that’s made a trip to a musical an essential rite of passage for fortunate children.

1997: Side Show

This story of conjoined twin sisters who go into vaudeville was a commercial flop, despite its excellent score and the exquisite staging by choreographer Robert Longbottom. But given the current vogue for musicals about outcasts, it was probably just way ahead of its time—see Next to Normal, Fun Home and Dear Evan Hansen.

2000: Contact

After AIDS had decimated the ranks of Broadway dancers and choreographers, and British mega-musicals had diminished their importance, this show brought new life to the Broadway dance scene. Previous all-dance shows were choreographic anthologies, like Fosse’s Dancin’ and Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. With this trio of one-acts, Susan Stroman proved to Broadway that you could tell a story through choreography alone, paving the way for Twyla Tharp‘s monumental Movin’ Out and who knows what else.

2008: In the Heights

This show reminded Broadway that the kind of seamlessly through-danced book musical pioneered by Robbins wasn’t, and would never become, obsolete—it just needed a choreographer like Andy Blankenbuehler to make it soar. Christopher Wheeldon then stepped up with An American in Paris and Blankenbuehler with Hamilton, and there’s undoubtedly more to come.

2012: Once

The British team of director John Tiffany and his movement colleague Steven Hoggett created a musical in which everybody—even the band—danced but nobody danced, opening the door to the post-choreography choreography of musicals like Come From Away and Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812. They’re pointing musicals in a new direction—stay tuned for another 60 years to see what happens.